Crusade ideology can be described as the ideas and the modes of perception that defined and justified the institution of the crusade and informed the way in which people at the time conceptualized crusades and the crusade movement. The ideology of the crusade becomes apparent in all

Kinds of historical sources about crusading, most clearly in texts concerned with the definition, regulation, and promotion of crusades. Crusade ideology was based on both legal theory and theology. In legal and institutional terms, the idea of crusade rested on the twin pillars of the theory of holy war and the model of pilgrimage, which represented the collective and individual aspects characterizing the activity of crusading. The traditions of holy war and pilgrimage reached far back into the history of Christianity, its intellectual foundations, and pastoral practice, and both played important roles during the eleventh century, the period leading up to the First Crusade (1096-1099). In theological terms, crusading was couched in both Old and New Testament thought. Whereas crusades were presented as parallels to the wars fought by the people of Israel in the Old Testament with the help and on the instigation of God, the spirituality of the individual crusader was based on New Testament theology and seen in Christocentric terms as forming a personal relationship with Christ.

The ideology of the crusade thus rested on four principal elements: holy war theory, the model of pilgrimage, Old Testament history, and New Testament theology. Early on in the history of the crusade movement, these four elements were fused into one more or less coherent cluster of ideas, giving the crusade a firm intellectual foundation, which among other factors accounted for the dynamism and longevity of the institution of the crusade and the activity of crusading.

Holy War

The theory of holy war was central to the formation and justification of the idea of crusading. The medieval concept of holy war goes back to the idea of just war (Lat. bellum iustum) of antiquity, which was adapted to a Christian context by St. Augustine of Hippo. Based on his writings, theologians and canon lawyers from the eleventh century onward elaborated a full-fledged theory of Christian holy war (Lat. bellum sacrum). There were three main conditions that had to apply for a war to be called holy. First, holy war had to be initiated by a legitimate authority. Initially this meant the pope or the emperor, as they were understood to act with divine authority on the guidance or instigation of God as the supreme ruler of the universe. Later medieval theorists discussed the question whether the authority to call for a holy war might extend to princely rulers in general. Second, holy war required a just cause (Lat. causa iusta). The enemy had to have committed a seri-

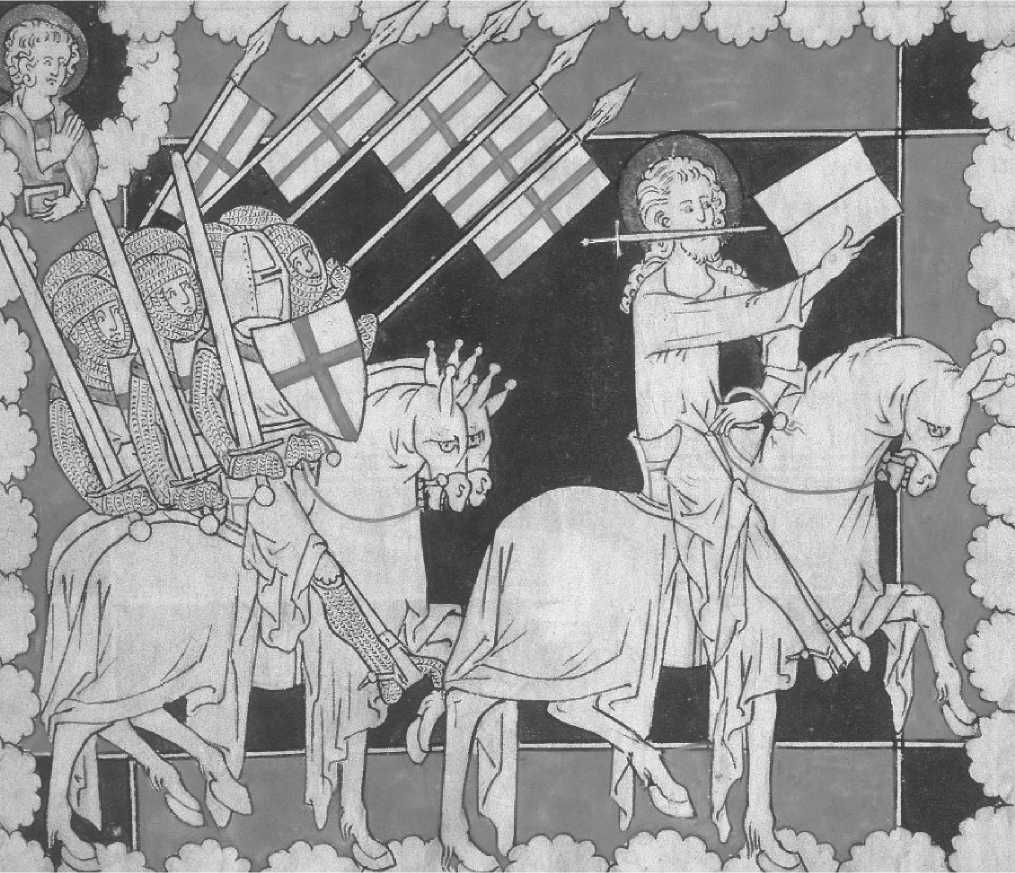

Crusaders led by Christ; above left is St. John the Evangelist, fourteenth century. Detail from The Apocalypse, roy.19.B. XV. Folio No: 37. British Library, London. (HIP/Art Resource)

Ous offense, overt aggression, or injurious action that justified the use of military force. In the case of holy war, the enemy had to have caused damage or insult or posed a threat to Christian religion in general or to peace and right order within Christian society. Third, holy war had to be conducted with the right intention (Lat. intentio recta). The initiators and participants of holy wars were supposed to act with pure motives and solely for the good of their religion and their fellow Christians. In essence, the Christian theory of holy war was meant to justify, in specific circumstances, the transgression of the divine prohibition of homicide enshrined in the Fifth Commandment.

The theory of holy war was fully elaborated in the twelfth century by the canonist Gratian and the Decretists and was given authoritative treatment by St. Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth. The suggestion of Hostiensis (Henry of Segusio) that holy war against non-Christians could be justified simply by their opposition to the Christian religion was never universally accepted. The theory of holy war underpinned some of the most important constitutive elements of the crusade. Legitimate authority was provided by reserving the right to call crusades to the papacy, based on the claim that God himself could authorize the crusade only through his vicar on earth, the pope. The character of the crusade as a war fought in defense of the church and for the support of the Christian religion was directed by the idea of just cause as laid down in the theory of holy war. The fact that crusaders took a vow and were supposed to lead an exemplary Christian life in accordance with that vow answered to the requirement of right intention applied to the individual participants. In general, the regulation of all aspects of crusading by canon law was meant to guarantee that crusades were called and conducted within the rules set down by the theory of holy war.

Pilgrimage

The tradition of pilgrimage provided the model for shaping the perception of the individual crusader. A crusade was thought of as a special pilgrimage, a journey both physical and spiritual in the service of God or Christ, rather than a particular saint. But whereas ordinary pilgrims traveled to a shrine to pray for the good of their own soul, crusaders were armed warriors, or at least members of an army, not only in pursuit of personal salvation. Crusaders were serving the church and making a personal effort to benefit the whole of the Christian community. In terms of legal obligations and privileges, the status of the crusader was closely modeled in the mold of pilgrimage. Like pilgrims, crusaders were in theory subject to ecclesiastical jurisdiction and enjoyed the legal protection of the church. In turn, crusaders vowed to serve in crusade armies on the conditions set out by the papacy. The model of pilgrimage was thus important for defining the legal position of crusaders and their relationship with church institutions. It also established the aspect of penance as a fundamental element of crusading. Both pilgrimage and crusade were in essence acts of penance by which individuals tried to cleanse their souls from sin.

In the case of the crusader, the act of penance was accorded special recognition because it was linked to a plenary indulgence promised by the popes. By earning a plenary indulgence, crusaders were believed to be granted the remission of all temporal penalties that God was said to impose on sinners. In the popular mind, the crusading indulgence provided the most comprehensive way of dealing with the consequence of sin and, for those who died on crusade, a direct way into heaven.

Old Testament History

From the very beginning of the crusade movement, crusades were described with reference to the wars fought by the Israelites, God’s chosen people of the Old Testament, for the recovery and the defense of the Promised Land. The most frequent parallels were drawn with the Israelites’ conquest of Canaan after the Exodus from Egypt and the wars of the Maccabees against the enemies of Israel. Both were perfect examples of wars fought by God’s people, led by the Lord against the enemies of his religion, and were well suited to serve as historical models for the crusades. This historical comparison suggested that, just as God initiated and supported the wars of his people in ancient times, so, too, he was the prime mover behind the contemporary crusades. The historical parallel thus emphasized the idea of the crusades as sacred warfare conducted with God’s authority and supported by the powers of divine grace. Individual exponents of these Old Testament wars, such as, for example, Joshua or Judas Maccabaeus, were also presented as figures to be emulated by the crusaders, heroes displaying extraordinary military prowess and war leaders who, trusting God’s commands in war, successfully fought for the good of their people and religion. The comparison with the wars of the Old Testament thus helped explain and justify the idea of the crusades as wars against enemies of the faith led by the church on behalf of God and fought by religious warriors.

New Testament Theology

Crusaders were viewed as soldiers of Christ (Lat. milites Christi) forming an army of Christ (Lat. militia Christi). Whereas prior to the First Crusade, the concept of the “soldier of Christ” was only used in a metaphorical sense (most often to describe monks), the transfer of the concept to secular soldiers fighting for the honor of the church and the defense of Christendom in essence created a type of Christian holy warrior. From the end of the twelfth century the most common way of referring to a crusader was the Latin word crucesigna-tus (male) or crucesignata (female), meaning “one signed by/with the cross.” This referred to the crosses of cloth that crusaders attached to their garments as an outward sign of their crusading vow, starting with the First Crusade of 1095.

As a symbol, the crusader’s cross represented the True Cross of Christ. The religious significance of the Cross of Christ shaped the ideas informing the individual crusader’s spirituality, which was seen in terms of forming a special relationship with Christ. Taking the cross made the crusader a follower and devotee of Christ responding to the New Testament call “to carry one’s cross and follow [Christ]” (Luke 9:23).

The special relationship between crusader and God was understood to be governed by the mechanisms of love, duty, and reward (largesse). The crusader expressed his love of God by taking upon himself the duty of fighting in the army of the crusades or supporting the crusades by other means, such as money or prayer. God returned his love for the crusader by letting him or her participate in the powers of redemption of Christ’s death on the cross and saving his or her soul from the punishments of sin. The cross thus symbolized the crusader’s devotion to Christ as well as the penitential aspect of the act of crusading. It was this personal relationship between crusader and God that, based on the theology of redemption and salvation, marked the core of the crusader’s spirituality. This explained why it was believed that, in principle, everybody could become a crusader, irrespective of gender, wealth, or social standing.

At times, the act of crusading was also seen as a form of imitation of Christ (Lat. imitatio Christi), an act of sacrifice motivated by charity for one’s fellow Christians after the example of Christ’s suffering for humankind. Crusaders who died on campaign were sometimes said to imitate Christ in the most radical way, by giving their lives as martyrs in imitation of Christ’s death on the cross.

The New Testament, in particular the figure of Christ, also played an important role in justifying specific crusades on a spiritual level. Thus, for example, the Holy Land was represented as the patrimony of Christ that the crusaders were recovering on God’s behalf. The Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229) was called a war in defense of the French church as the spouse of Christ; the Baltic Crusades were conceptualized as campaigns to conquer for Christianity lands beloved of Mary, the mother of Christ.

Conclusions

The theory of holy war, the model of pilgrimage, Old Testament precedent, and New Testament theology were the main foundations of crusade ideology. The combination of these four elements was what made crusade ideology distinct from the ideology of other types of religious wars or devotional activities. The perception of the crusade as a holy war was set against the background of historical parallels with the wars of the Israelites in the Old Testament. This combined the idea of a war led by the church for the good of

Christianity with the concept of a war initiated by divine authority and fought by God’s chosen people. The idea of pilgrimage as a devotional activity imbued in New Testament theology contributed toward the definition of a specific crusader spirituality. In ideal terms, the crusader was seen as a special pilgrim who carried arms or actively supported a military venture and whose spiritual journey in the act of crusading was aimed at salvation by forming a closer relationship with God or Christ.

From the beginning of the movement, crusading was closely associated with the recovery of Jerusalem and the Christian holy places in Palestine. The symbolic significance of Jerusalem in Christian history, in particular as the setting for Christ’s act of redemption, was pivotal in bringing about the First Crusade and successfully establishing the institution of crusading. This explains why throughout the Middle Ages crusades to the Holy Land always met with the greatest enthusiasm and support and gave the most forceful expression to the idea of the crusader as a soldier fighting on Christ’s behalf.

But the idea of crusading was not exclusively tied to the significance and symbolism of Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Already in the first half of the twelfth century the practice of crusading was transferred to other theaters of war between Christians and non-Christians on the periphery of Christian Europe, in particular on the Iberian Peninsula, where crusading became an integral element of the Reconquista, and in northeastern Europe in the wars against the Wends. By the thirteenth century the crusade movement also encompassed the missionary crusades in the Baltic region, wars against dissident groups of heretics in France, Germany, and Hungary, and campaigns against political enemies of the papacy in Italy and elsewhere.

Common factors in all these conflicts were their authorization by the papacy and justification as wars fought for the integrity of the church and the honor and defense of Christendom. Crusade ideology was thus closely linked to the medieval concept of Christendom as one single Christian community represented by the church, headed by the papacy, and distinguished from all nonbelievers (Lat. gentiles). The crusades were called by the pope as the spiritual leader of Christendom, were fought by participants from all over Christendom, and were aimed at furthering the cause of Christendom and the Christian religion in its entirety.

Crusade ideology was surprisingly uniform throughout the centuries spanned by the crusade movement. Its formation, vitality, and survival were ultimately dependent on two principal factors: the idea of Christendom as a geopolitical reference, and the penitential practice of the medieval church. The rise and fall of the idea of Christendom represented by one church led by the pope, which was actively promoted by the Gregorian Reformers of the eleventh century and died down in the aftermath of the Reformation, mirrored the beginning and end of the idea and the practice of crusading. By the same token, the universal acceptance of penitential practice and the belief in the effectiveness of the indulgence enshrined in Roman Catholic doctrine, which were preconditions for creating and sustaining the ideology of the crusade, gained momentum with the crusade movement and were dealt a serious blow during the Reformation. Even though the ideology of the crusade was kept alive after the sixteenth century, most notably in the aspirations of the military orders, its impact dwindled as the arrival of other forms of religious wars led to the formation of new ideologies.

-Christoph T. Maier

See also: Chivalry; Eschatology; Holy War; Indulgences and Penance; Just War; Cross, Symbol; Motivation; Sermons and Preaching

Bibliography

Brundage, James A., Canon Law and the Crusader (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969).

Hehl, Ernst-Dieter, Kirche und Krieg im 12. Jahrhundert: Studien zu kanonischem Recht undpolitischer Wirklichkeit (Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1980).

Housley, Norman, The Italian Crusades: The Papal-Angevin Alliance against Christian Lay Powers, 1254-1343 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982).

-, Religious Warfare in Europe, 1400-1536 (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2002).

Maier, Christoph T., Crusade Propaganda and Ideology: Model Sermons for the Preaching of the Cross (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Riley-Smith, Jonathan, “Crusading as an Act of Love,” History 65 (1980), 177-192.

-, What Were the Crusades?, 3d ed. (London: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2002).

Rousset, Paul, Histoire d’une ideologie: La Croisade (Lausanne: Editions l’Age d’Homme, 1983).

Russell, Frederick H., The Just War in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975).

World History

World History