... [T]o me, and many others of us, these two [Justinian and Theodora] seemed not to be human beings, but veritable demons, and what the poets call vampires: who laid their heads together to see how they could most easily and quickly destroy the race and deeds of men; and assuming human bodies, became man-demons, and so convulsed the world. And one could find evidence of this in many things, but especially in the superhuman power with which they worked their will.

For when one examines closely, there is a clear difference between what is human and what is supernatural. There have been many enough men, during the whole course of history, who by chance or by nature have inspired great fear, ruining cities or countries or whatever else fell into their power; but to destroy all men and bring calamity on the whole inhabited earth remained for these two to accomplish, whom Fate aided in their schemes of corrupting all mankind. For by earthquakes, pestilences, and floods of river waters at this time came further ruin, as I shall presently show. Thus not by human, but by some other kind of power they accomplished their dreadful designs.

And they say his mother said to some of her intimates once that not of Sabbatius her husband, nor of any man was Justinian a son. For when she was about to conceive, there visited a demon, invisible but giving evidence of his presence perceptibly where man consorts with woman, after which he vanished utterly as in a dream.

And some of those who have been with Justinian at the palace late at night, men who were pure of spirit, have thought they saw a strange demoniac form taking his place. One man said that the

Emperor suddenly rose from his throne and walked about, and indeed he was never wont to remain sitting for long, and immediately Justinian's head vanished, while the rest of his body seemed to ebb and flow; whereat the beholder stood aghast and fearful, wondering if his eyes were deceiving him. But presently he perceived the vanished head filling out and joining the body again as strangely as it had left it.

Another said he stood beside the Emperor as he sat, and of a sudden the face changed into a shapeless mass of flesh, with neither eyebrows nor eyes in their proper places, nor any other distinguishing feature; and after a time the natural appearance of his countenance returned. I write these instances not as one who saw them myself, but heard them from men who were positive they had seen these strange occurrences at the time.

They also say that a certain monk, very dear to God, at the instance of those who dwelt with him in the desert went to Constantinople to beg for mercy to his neighbors who had been outraged beyond endurance. And when he arrived there, he forthwith secured an audience with the Emperor; but just as he was about to enter his apartment, he stopped short as his feet were on the threshold, and suddenly stepped backward. Whereupon the eunuch escorting him, and others who were present, importuned him to go ahead. But he answered not a word; and like a man who has had a stroke staggered back to his lodging. And when some followed to ask why he acted thus, they say he distinctly declared he saw the King of the Devils sitting on the throne in the palace, and he did not care to meet or ask any favor of him.

Indeed, how was this man likely to be anything but an evil spirit, who never knew honest satiety of drink or food or sleep, but only tasting at random from the meals that were set before him, roamed the palace at unseemly hours of the night, and was possessed by the quenchless lust of a demon?

Furthermore some of Theodora's lovers, while she was on the stage, say that at night a demon would sometimes descend upon them and drive them from the room, so that it might spend the night with her. And there was a certain dancer named Macedonia, who belonged to the Blue party in Antioch, who came to possess much influence. For she used to write letters to Justinian while Justin was still Emperor, and so made away with whatever notable men in the East she had a grudge against, and had their property confiscated.

Wont: Inclined.

Ebb and flow: In this context, "appear and disappear."

Whereat: At which point.

Beholder: Someone seeing something.

Aghast: Amazed.

Countenance: Face.

Monk: A religious figure who pursues a life of prayer and meditation.

Instance: Request.

Forthwith: Immediately.

Audience: Meeting.

Apartment: Room or

Chamber.

Eunuch: A man who has been castrated, thus making him incapable of sex or sexual desire; kings often employed eunuchs on the belief that they could trust them around their wives.

Importuned: Urged.

Stroke: A sudden brain-seizure that renders the victim incapable of movement or speech.

Satiety: Satisfaction.

Unseemly: Inappropriate or improper.

Quenchless: Unsatisfiable. Made away with: Got rid of.

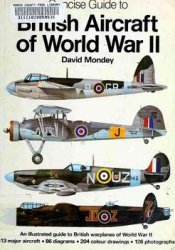

Justinian and Theodora

One would not know it from Procopius's Secret History, but many historians of the Byzantine Empire view Justinian (483-565; ruled 527-565) as its greatest ruler. Justinian laid the foundations for modern law with his legal code, or system of laws, completed in 535; and under his rule, Byzantine arts flourished.

Even Procopius had to admit that Justinian built a number of great structures, none more notable than the church known as the Hagia (HAH-jah) Sophia. An architectural achievement as impressive today as it was some 1,500 years ago, the Hagia Sophia dominates the skyline of Istanbul, Turkey, which in medieval times was the Byzantine capital of Constantinople (kahn-

Stan-ti-NOH-pul). Also during Justinian's time, the Byzantine art of mosaics (moh-ZAY-iks)—colored bits of glass or tile arranged to form a picture—reached a high point. The most famous Byzantine mosaics are those depicting Justinian and his wife Theodora, which can be found in Italy's Church of San Vitale.

The Byzantine presence in Italy was an outgrowth of the most visible, yet least enduring, achievement of Justinian's era. Hoping to reclaim the Western Roman Empire, which had fallen to invading tribes in 476, Justinian sent his general Belisarius (c. 500-565) on three military campaigns that won back North Africa in 534, Italy in 540, and southern Spain in 550. These were

Cast down: Depressed.

The leader of a chorus of coins: In other words, wealthy.

Share the couch of: Engage in marital relations with.

Contrive: Plan.

Mistress: Female head of a household.

This Macedonia, they say, greeted Theodora at the time of her arrival from Egypt and Libya; and when she saw her badly worried and cast down at the ill treatment she had received from Hecebolus and at the loss of her money during this adventure, she tried to encourage Theodora by reminding her of the laws of chance, by which she was likely again to be the leader of a chorus of coins. Then, they say, Theodora used to relate how on that very night a dream came to her, bidding her take no thought of money, for when she should come to Constantinople, she should share the couch of the King of the Devils, and that she should contrive to become his wedded wife and thereafter be the mistress of all the money in the world. And that this is what happened is the opinion of most people.

Costly victories, however, and except for a few parts of Sicily and southern Italy, the Byzantines did not hold on to their conquests past Justinian's lifetime.

As for Theodora (c. 500-548), she had been an actress before she married Justinian—and in those days, actresses were looked upon as little better than prostitutes, and in fact many actresses were prostitutes. It is doubtful, however, that her morals were nearly as loose as Procopius portrays them in his X-rated account from the Secret History, "How Theodora, Most Depraved of All Courtesans, Won His Love." In any case, after Theodora married Justinian and became empress, she proved

Herself a great help to her husband—and a leader in her own right.

When the citizens of Constantinople revolted against Justinian in 532, the emperor was slow to act, and considered fleeing the palace. Theodora, however, stirred him to action when she said, "For my own part, I hold to the old saying that the imperial purple makes the best burial sheet"—in other words, it is better to die defending the throne than to run away. Thus Justinian maintained power, and went on to the many achievements that marked his reign. When Theodora died in 548, Justinian was heartbroken.

World History

World History