Ireland had not been a part of the Roman Empire as had Britain, but commercial contact had existed. There were also occasional Irish raids on Roman Britain, especially in search of slaves. One such slave captured in the early fifth century was a young man named Patrick, of Roman-Briton background, whose father was a deacon in the Christian Church. Patrick spent six years in captivity during which he regained the religious faith of his youth. Following a voice in a dream alerting him that a ship would take him home, he escaped, traveled twenty miles, came upon the ship, and did ultimately return home. Then a message in another dream urged him to return to Ireland. Before doing so he studied for the priesthood and became a bishop. He came back to convert thousands of the Irish to Christianity. Patrick was not the only Christian missionary to Ireland and there were Christians in Ireland before him. Furthermore, he scarcely converted all the Irish—large numbers, even some nominally Christian converts, continued to adhere to pre-Christian beliefs for sometime afterward. More than likely, his mission was concentrated in the northern half of the island as the present provinces of Munster and Leinster probably had Christian communities preceding Patrick. But his impact must have been of some significance to warrant the subsequent hagiography, which titles him Apostle to the Irish. The island would never be the same. Within a few centuries Ireland became a major center for the study and preservation of religious and classical thought in a Europe where the Roman Empire had disintegrated, to be replaced by political and social disorder and economic retrogression.

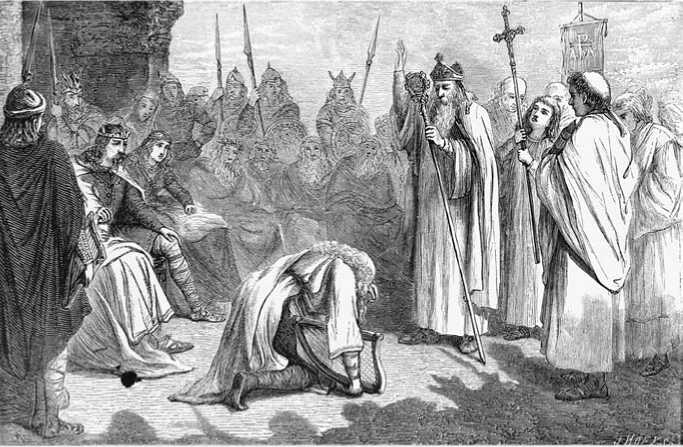

The Bard, with harp, kneeling in front of St. Patrick. Engraving by Joseph Hoey (Library of Congress)

Important social factors inhibited the effort of churchmen to duplicate in Ireland the institutional and disciplinary structure of the European continent. There the leaders of the church were the bishops, who ruled dioceses centered in cities, as had the local political authorities in the Roman Empire. Because Ireland had no cities, it was difficult to apply the same pattern. The territorial boundaries of the tuatha were often in flux as their people were relatively mobile or migratory. Such a situation was not amenable to a diocesan ecclesiastical structure. In addition, ri, the local rulers, were amenable neither to alienating property within the tuath to outsiders nor to allowing outsiders to occupy positions within. It was expected that the occupants of church property and office should come from within the tuatha and be kinfolk of the previous occupant. Rulers found it more to their liking to endow monastic settlements as a means of guaranteeing the exclusion of outside influences. Furthermore, to the degree both that monasteries were located within a tuatha and that the founder or leader enjoyed celebrity status, abbots began to assume a position of significance or importance in the church exceeding that of the bishop, who became more confined to the sanctifying rather than the ruling functions of his office.

Irish monasticism was eremitic, similar to that found in the eastern Mediterranean in its emphasis on asceticism and isolation, and unlike the highly disciplined settlements that would draw their founding inspiration during the late sixth and early seventh centuries from the rule of St. Benedict. Paradoxically, that very isolation drew followers that led inevitably to communities, but communities of individualized cells. A classic example of this pursuit of hermitage and closeness to God in a remote and inaccessible place was the celebrated Skel-lig Michael, a monastic settlement whose cells remain intact today 700 feet above sea level on a remote rocky island seven miles off the coast of Kerry in southwest Ireland. Irish monasticism retained this character until the arrival of continental influences during the High Middle Ages. The sixth century saw the appearance of a multitude of these monasteries, among the more notable that of Clonard, Clonmacnoise, and Clonfert.

Other distinguishing features of the Irish church included variations in the liturgical calendar and a different tonsure for clergy (the Irish would shave the front half of the head rather than the rear top like the continental monks). Centuries later this would lead a reforming papacy to harbor serious anxieties about the Irish church, especially in view of the persistence of pre-Christian attitudes, particularly with regard to marital codes.

A remarkable feature of the hermetical impulse driving the monks was the inclination to undertake the peregrinatio, that is, a pilgrimage for Christ, which would entail wandering across the ocean away from Ireland. One example was the voyage of St. Brendan, which some claim went as far as North America. More significant in their historical impact were the peregrinations of Colm Cille and Columbanus. Colm Cille, a member of the Ui Neills, one of the ruling families of ancient Ireland, led a handful of followers from Derry to Scotland, where he played the same role there as Patrick had in Ireland. Some argue than he, rather than St. Andrew, should be the patron saint of Scotland. His influence would extend down to northern England in contributing to the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons, although at the Council of Whitby in the mid-seventh century the Anglo-Saxon church deferred to the tradition that had emanated from St. Augustine in adopting the Roman model in terms of church organization, liturgy, and discipline.

In the same sixth century that Colm Cille had gone to Scotland, Columbanus led his followers on a pilgrimage to the Continent. His group traveled through Gaul and ultimately reached Bobbio in Italy; Their influence and their settlements also developed in Belgium, Germany, and Switzerland.

The Irish monasteries were noted not just for asceticism but also for learning. They became renowned as schools abroad as well as at home. Bede, the great historian of Anglo-Saxon England, noted how many English went to Ireland to study. The Irish monks became masters of classical Latin, but they also began to write down the Celtic folklore, although blending it with a Christian perspective. The monasteries became the great centers for artistic work, noted especially for producing illuminated manuscripts of the scriptures like the Book of Durrow and later the Book of Kells. Perhaps the most famous product of Irish schools who made his way to the continent was John Scotus Eruigena, who remained for a quarter of a century as the chief professor at the school of Emperor Charles the Bald, and who was regarded as one of the leading intellects of the post-Carolin-gian renaissance of the ninth century. He was pictured on the five-punt note in the Irish currency that was replaced in 2001 by the common European currency. His work included commentaries on the Gospel of St. John and the theology of Boethius. Some suggested his speculative work was heretical, but he insisted on his orthodoxy and his work provided the first great synthesis of theology, one that would not be rivaled until that of Thomas Aquinas in the 13 th century.

As mentioned earlier, the monasteries became intertwined with ecclesiastical and political ambitions, as various kings and bishops sought to assert their rival claims of ascendancy. St. Patrick's hagiography developed in connection with the efforts of the See of Armagh to claim ecclesiastical primacy over Kildare and with the Ui Neill claim to the high kingship on the basis of their connection to Tara, a site of remarkable apostolic achievement by Patrick. On a more local basis, patrons of monasteries obviously supported efforts to celebrate saintly figures whose remains were interred on the grounds within their political domain. An inevitable consequence of the development of such secular interests was a certain corruption of the monastic ideal, as evidenced by the tendency of abbots to succeed by inheritance, suggesting that celibacy was not always the rule.

Politically, Ireland remained divided into scores of small kingdoms. But there were various alliances of smaller kingdom under great kings, some of which made rival claims for the high kingship of Ireland. But much of the authority of the greater kings was symbolic and significant only for genealogical reasons. The topographic conditions of the island, with its mountains, forests, and bogs, inhibited much effective and regular communication, never mind political centralization. Ireland lay exposed and, like much of the rest of Western Europe, would fall prey, by the end of the eighth century, to the incursions of the Vikings.

World History

World History