Between 800 and 1100 the peoples of Scandinavia went from being an Iron Age to a fully medieval society. The profound social transformations are reflected in the changes in their adventurous expeditions and in their use of silver at home. Before 800 silver wealth was stored in jewellery, often huge arm rings or brooches. We assume many of these circulated as gifts, bride wealth, blood money and plunder. By the twelfth century kings had coins minted bearing their likeness and most silver, in the shape of coins, was used in straightforward financial exchanges or the payment of rent or taxes or tithes. Whether silver was the motor of social change or simply an indispensable element of political and social competition in an increasingly hierarchical Scandinavian society, the Vikings burst out of their homeland dramatically and often terrifyingly in search of it.

In the ninth century they raided and traded for silver, but to call these early Vikings merchants is anachronistic. In Iceland's famous

Njalssaga, a main character attempts to obtain hay from a neighbour, asking if he would sell it to him (denying any social relationship between them), next if he would give it to him as a gift (offering future friendship), and finally he had to threaten to take it (confirming their enmity).

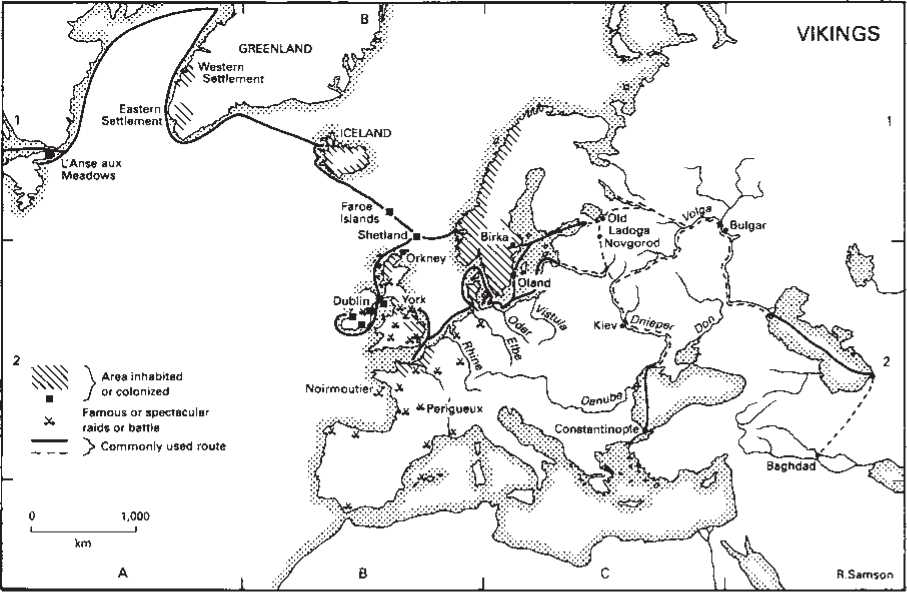

In the east, Swedes travelled huge distances trading and swapping, buying and selling, gifting and stealing at entrepots and towns at Old Ladoga, Novgorod, Kiev and Bulgar. The major Russian rivers, the Dnieper, Don and Volga were their highways. At the end of these rivers lay Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire, but more importantly the caliphate of Baghdad and tons of Islamic silver. More than 85,000 Arabic coins have been found in Scandinavia. Although little appreciated today, contact with German and Slavic regions, along the coast and down the Oder and Vistula, was probably equally intense. More than 70,000 German coins have been discovered in Sweden.

While Vikings certainly traded around the British Isles, much silver was probably the fruit of violence. From the raid on the monastery at Lindisfarne in 793 or at Noirmoutier to the battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066, the violence grew from plundering raids of single boats to huge invasion armies. Even the big armies were interested primarily in silver, extracting tribute, the so-called Danegeld. Between 991 and 1014 they received more than 150,000lbs of silver officially, which is equal to 36 million coins!

The change from raids of small bands to huge armies reflects the changes in the Scandinavian societies at home. As political power became more centralized, economic and social organization in Scandinavia came to resemble that of other European nations. The final Scandinavian invasions resembled the wars of their neighbours; they aimed at conquest. Northmen would rule Normandy and give it their name; Danish law would run for much of eastern England (hence Danelaw); Canute would later be king of all England; and much of Ireland would be politically dominated by the

Scandinavian kingdom based at Dublin until the battle of Clontarf in 1014.

Perhaps as the result of tensions in Scandinavia during this period of accelerated political centralization, many Norwegians left to settle lands in the North Atlantic: Shetland, Orkney, the Hebrides, Man, the Faroes, Greenland, and even North America. Certainly this is one of the mythical reasons the Icelandic sagas give for the original leaving of Norway. In these new lands the Norse may not have found identical climates and landscapes, but they were similar enough to allow old lifestyles to be perpetuated. Moreover, these islands were uninhabited or only sparsely inhabited.

The distances the Vikings travelled, their 'primitiveness' and their paganism impressed and frightened the peoples of more settled Europe of the ninth and tenth century. Their incomprehension has left us the Vikings of myth and legend.

R. Samson

Magyars

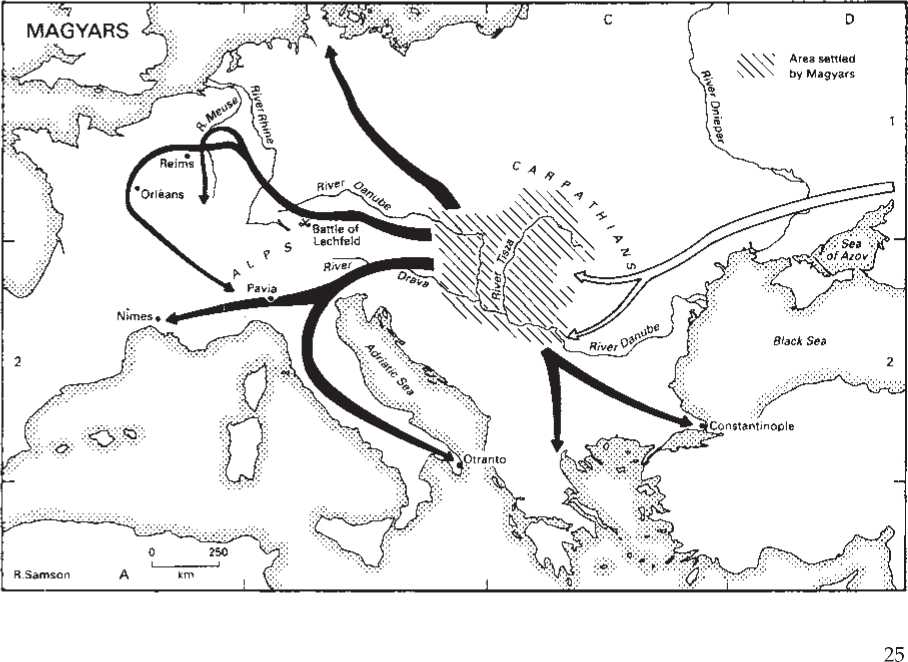

Where the Magyars came from we shall never is their own name for themselves) first appeared know. Their language, of a Finno-Ugrian type, is in written sources only in 833 around the Sea of said most closely to resemble that of some Azov when they attacked the Khazars. Thirty aboriginals of Siberia. The Hungarians (Magyar years later a raiding expedition had reached

German borders. In 896 they entered the great Alfold basin, between the Danube and the Tisza, ringed by the Beskidy in the north, Carpathians in the east, Alps in the west, and Dinaric Alps in the south.

The plains here had been home to nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples since later prehistory. Like the Huns and the Avars before them, the Magyars, accomplished horsemen, plundered and pillaged far and wide. In 899 they attacked settlements along the Po river; in Italy they raided as far south as Otranto. In 900 they plundered Bavaria, and Germany was to bear the brunt of their unwanted attention. After 917 they regularly pillaged northern Gaul and in 924 they attacked the area of Nimes.

Henry I of Germany had fortifications built against the Magyars, his son Otto I charged the frontier guardians with the duty of protecting the empire from their incursions. Little else was done to lessen the threat, nothing like Charlemagne's massive invasion of the Avar kingdom. In 955 Otto I defeated a band of marauders at Lechfeld as they returned home with booty.

The date more or less marked the end of the Magyar raids, which had lasted less than a century. Latterly they had become less frequent but the lost battle cannot have ended them. It seems inescapable that raids ended because of internal developments on the Alfold plain. The medieval Hungarian state was developing. The conversion to Christianity had begun with the work of Bishop Pilgrim of Passau (971-91). In 1001 Vaik, with the baptismal name of Stephen, took the title of king. By papal consent Hungary received its own metropolitan, thereby escaping the rival claims of Passau and the Greek Church, which had also sent missionaries.

When next Hungarians and Germans did battle, it was in wars between neighbouring kingdoms.

R. Samson

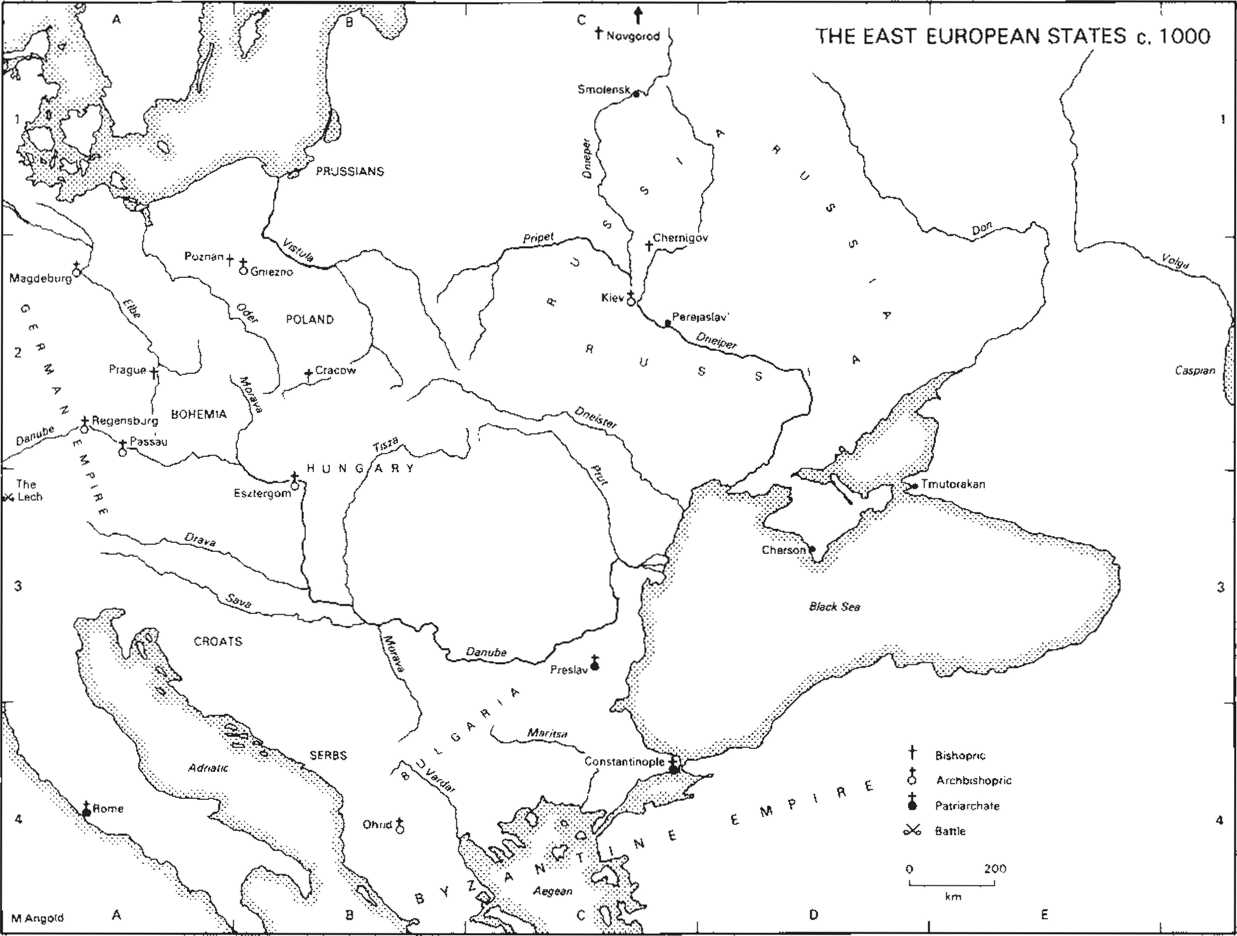

The East European States, c. 1000

Although there were few precise frontiers, by 1000 the political map of eastern Europe was becoming better defined. This was outwardly a matter of the conversion of the peoples of the region to Christianity and of the advance of dynastic claims at the expense of tribal loyalties. It also involved the question of political affiliation with the Byzantine and/or German empires. Bulgaria provides a precocious example. Caught between the two empires its ruler Boris finally accepted Christianity from Byzantium in 865 and with it Byzantine claims to overlordship. He concentrated on the conversion of his people, both the Bulgar elite and the Slav tributaries. It helped both to strengthen his dynastic authority and to unify his people. It was left to his son Symeon to challenge Byzantium. He assumed the imperial title and claimed patriarchal status for the Bulgarian Church. His ambitions led to war with Byzantium. His death in 927 temporarily ended hostilities, but Byzantium could not tolerate so potentially dangerous a competitor on its doorstep. The Byzantines finally destroyed all Bulgarian resistance in 1018 and annexed the country.

The Russians too were a threat, on occasion attacking Constantinople. They were originally Scandinavian freebooters who controlled the river routes from the Baltic to the Caspian and the Black Sea. They made Kiev their main centre and put the surrounding Slav tribes under tribute. Their warrior ethos militated against conversion to Christianity, which was delayed until the years 987-9, in the course of which Vladimir, the prince of Kiev, accepted Christianity from Byzantium. This he did on his own terms, because of the temporary weakness of the Byzantine emperor. He obtained the hand of the emperor's sister in marriage, which gave him enormous prestige. These circumstances meant that Byzantine political claims over Russia were always muted. It meant that there was no

Need for the prince of Kiev to claim imperial status. Power remained in the hands of the ruling family. The Russian lands continued to be divided into a series of shifting principalities over which the prince of Kiev merely presided as senior member. At the head of the Russian Church was the metropolitan of Kiev. He may have been appointed from Constantinople, but there was a close identification of the Church with the ruling family: Vladimir was revered as its founder and his murdered sons Boris and Gleb were venerated as martyrs.

The Russians thus managed to solve the dilemma which led to the destruction of the Bulgarian Empire: how to avoid the political entanglements involved in conversion to Christianity. This dilemma was also apparent in the dealings of the western Slavs with the German Empire. Bohemia had to accept a large measure of German domination. In 973 its ruler recognized the suzerainty of the German emperor, Otto I, and the see of Prague was subordinated to Mainz, but the native Premyslid dynasty continued in power thanks to the posthumous reputation of Duke Wenceslas, who was murdered in 929 and was soon revered as the national saint of Bohemia.

In the face of German encroachment the pagan Polish ruler tried to learn from the experience of Bohemia. He married a Bohemian princess and in 966 accepted Christianity voluntarily rather than have it forced upon him. Shortly before his death in 992 he made the 'Donation of Poland' to the papacy in order to block German claims over the Church in Poland. Under his brother Boleslav the independence of Poland was formally recognized by the German emperor, Otto III, in 1000, at a ceremony to inaugurate the Polish archbishopric of Gniezno, though no royal title was accorded.

The ceremony was solemnized by the translation of the relics of St Adalbert of Prague, recently martyred by the pagan Prussians. Adalbert came from a noble Bohemian family and was made bishop of Prague in 982. Most of his energies were devoted to evangelizing the lands to the east. He worked among the Poles and among the Hungarians, who had terrorized far and wide until their defeat in 955 by Otto I at the battle of the Lech. In 995 Adalbert baptized the Hungarian ruler Geza and his son, the future St Stephen, who in 1000 obtained a royal crown from the papacy. A Hungarian archbishopric was established at Esztergom. There are clear parallels between Hungary and Poland. Both turned to the papacy as a means of countering German domination. Boleslav of Poland would follow St Stephen's example and in 1025 obtained the royal crown denied him by the Germans from the papacy.

M. Angold

World History

World History