A GLEAM OF SPLENDOUR FALLS ACROSS THE DARK, TROUBLED STORY of medieval England. Henry V was King at twenty-six. He felt, as his father had never done, sure of his title. He had spent his youth in camp and Council; he had for five or six years intermittently conducted the government of the kingdom during his father’s decline. The romantic stories of his riotous youth and sudden conversion to gravity and virtue when charged with the supreme responsibility must not be pressed too far. It may well be true that “he was in his youth a diligent follower of idle practices, much given to instruments of music, and fired with the torches of Venus herself.” But if he had thus yielded to the vehement ebullitions of his nature this was no more than a pastime, for always since boyhood he had been held in the grasp of grave business.

In the surging realm, with its ailing King, bitter factions, and deep social and moral unrest, all men had for some time looked to him; and succeeding generations have seldom doubted that according to the standards of his day he was all that a king should be. His face, we are told, was oval, with a long, straight nose, ruddy complexion, dark, smooth hair, and bright eyes, mild as a dove’s when unprovoked, but lion-like in wrath; his frame was slender, yet well-knit, strong and active. His disposition was orthodox, chivalrous and just. He came to the throne at a moment when England was wearied of feuds and brawl and yearned for unity and fame. He led the nation away from internal discord to foreign conquest; and he had the dream, and perhaps the prospect, of leading all Western Europe into the high championship of a Crusade. Council and Parliament alike showed themselves suddenly bent on war with France. As was even then usual in England, they wrapped this up in phrases of opposite import. The lords knew well, they said, “that the King will attempt nothing that is not to the glory of God, and will eschew the shedding of Christian blood; if he goes to war the cause will be the renewal of his rights, not his own wilfulness.” Bishop Beaufort opened the session of 1414 with a sermon upon “Strive for the truth unto death” and the exhortation “While we have time, let us do good to all men.” This was understood to mean the speedy invasion of France.

The Commons were thereupon liberal with supply. The King on his part declared that no law should be passed without their assent. A wave of reconciliation swept the land. The King declared a general pardon. He sought to assuage the past. He negotiated with the Scots for the release of Hotspur’s son, and reinstated him in the Earldom of Northumberland. He brought the body, or reputed body, of Richard II to London, and reinterred it in Westminster Abbey, with pageantry and solemn ceremonial. A plot formed against him on the eve of his setting out for the wars was suppressed, by all appearance with ease and national approval, and with only a handful of executions. In particular he spared his cousin, the young Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, who had been named as the rival King, through whose family much that was merciless was to follow later.

During the whole of 1414 Henry V was absorbed in warlike preparations by land and sea. He reorganised the Fleet. Instead of mainly taking over and arming private ships, as was the custom, he, like Alfred, built many vessels for the Royal Navy. He had at least six “great ships,” with about fifteen hundred smaller consorts. The expeditionary army was picked and trained with special care. In spite of the more general resort to fighting on foot, which had been compelled by the long-bow, six thousand archers, of whom half were mounted infantry, were the bulk and staple of the army, together with two thousand five hundred noble, knightly, or otherwise substantial warriors in armour, each with his two or three attendants and aides.

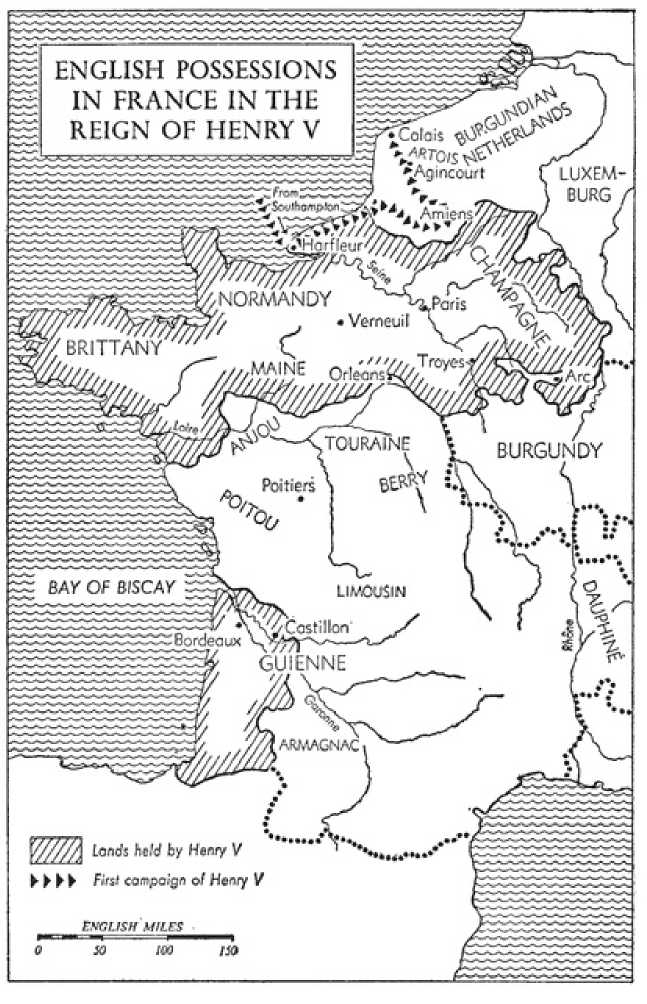

In 1407 Louis, Duke of Orleans, the decisive power at the Court of the witless French King, Charles VI, had been murdered at the instigation of the Duke of Burgundy, and the strife of the two parties which divided France became violent and mortal. To this the late King of England had owed the comparative relief from foreign menace which eased the closing years of his reign. At Henry V’s accession the Orleanists had gained the preponderance in France, and unfurled the Oriflamme against the Duke of Burgundy. Henry naturally allied himself with the weaker party, the Burgundians, who, in their distress, were prepared to acknowledge him as King of France. When he led the power of England across the Channel in continuation of the long revenge of history for Duke William’s expedition he could count upon the support of a large part of what is now the French people. The English army of about ten thousand fighting men sailed to France on August 11, 1415, in a fleet of small ships, and landed without opposition at the mouth of the Seine. Harfleur was besieged and taken by the middle of September. The King was foremost in prowess:

Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more;

Or close the wall up with our English dead.

In this mood he now invited the Dauphin to end the war by single combat. The challenge was declined. The attrition of the siege, and disease, which levied its unceasing toll on these medieval camps, had already wrought havoc in the English expedition. The main power of France was now in the field. The Council of War, on October 5, advised returning home by sea.

But the King, leaving a garrison in Harfleur, and sending home several thousand sick and wounded, resolved, with about a thousand knights and men-at-arms and four thousand archers, to traverse the French coast in a hundred-mile march to his fortress at Calais, where his ships were to await him. All the circumstances of this decision show that his design was to tempt the enemy to battle. This was not denied him. Marching by Fecamp and Dieppe, he had intended to cross the Somme at the tidal ford, Blanchetaque, which his great-grandfather had passed before Crecy. Falsely informed that the passage would be opposed, he moved by Abbeville; but here the bridge was broken down. He had to ascend the Somme to above Amiens by Boves and Corbie, and could only cross at the ford of Bethencourt. All these names are well known to our generation. On October 20 he camped near Peronne. He was now deeply plunged into France.

It was the turn of the Dauphin to offer the grim courtesies of chivalric war. The French heralds came to the English camp and inquired, for mutual convenience, by which route His Majesty would desire to proceed. “Our path lies straight to Calais,” was Henry’s answer. This was not telling them much, for he had no other choice. The French army, which was already interposing itself, by a right-handed movement across his front fell back before his advance-guard behind the Canche river. Henry, moving by Albert, Frevent, and Blangy, learned that they were before him in apparently overwhelming numbers. He must now cut his way through, perish, or surrender. When one of his officers, Sir Walter Hungerford, deplored the fact “that they had not but one ten thousand of those men in England that do no work to-day,” the King rebuked him and revived his spirits in a speech to which Shakespeare has given an immortal form:

If we are marked to die, we are enough

To do our country loss; and if to live,

The fewer men, the greater share of honour.

“Wot you not,” he actually said, “that the Lord with these few can overthrow the pride of the French?”1 He and the “few” lay for the night at the village of Maisoncelles, maintaining utter silence and the strictest discipline. The French headquarters were at Agincourt, and it is said that they kept high revel and diced for the captives they should take.

The English victory of Crecy was gained against great odds upon the defensive. Poitiers was a counter-stroke. Agincourt ranks as the most heroic of all the land battles England has ever fought. It was a vehement assault. The French, whose numbers have been estimated at about twenty thousand, were drawn up in three lines of battle, of which a proportion remained mounted. With justifiable confidence they awaited the attack of less than a third their number, who, far from home and many marches from the sea, must win or die. Mounted upon a small grey horse, with a richly jewelled crown upon his helmet, and wearing his royal surcoat of leopards and lilies, the King drew up his array. The archers were disposed in six wedge-shaped formations, each supported by a body of men-at-arms. At the last moment Henry sought to avoid so desperate a battle. Heralds passed to and fro. He offered to yield Harfleur and all his prisoners in return for an open road to Calais. The French prince replied that he must renounce the crown of France. On this he resolved to dare the last extremity. The whole English army, even the King himself, dismounted and sent their horses to the rear; and shortly after eleven o’clock on St. Crispin’s Day, October 25, he gave the order, “In the name of Almighty God and of Saint George, Avaunt Banner in the best time of the year, and Saint George this day be thine help.” The archers kissed the soil in reconciliation to God, and, crying loudly, “Hurrah! Hurrah! Saint George and Merrie England!” advanced to within three hundred yards of the heavy masses in their front. They planted their stakes and loosed their arrows.

The French were once again unduly crowded upon the field. They stood in three dense lines, and neither their cross-bowmen nor their battery of cannon could fire effectively. Under the arrow storm they in their turn moved forward down the slope, plodding heavily through a ploughed field already trampled into a quagmire. Still at thirty deep they felt sure of breaking the line. But once again the long-bow destroyed all before it. Horse and foot alike went down; a long heap of armoured dead and wounded lay upon the ground, over which the reinforcements struggled bravely, but in vain. In this grand moment the archers slung their bows, and, sword in hand, fell upon the reeling squadrons and disordered masses. Then the Duke of Alengon rolled forward with the whole second line, and a stubborn hand-to-hand struggle ensued, in which the French prince struck down with his own sword Humphrey of Gloucester. The King rushed to his brother’s rescue, and was smitten to the ground by a tremendous stroke; but in spite of the odds Alengon was killed, and the French second line was beaten hand to hand by the English chivalry and yeomen. It recoiled like the first, leaving large numbers of unwounded and still larger numbers of wounded prisoners in the assailants’ hands.

Now occurred a terrible episode. The French third line, still intact, covered the entire front, and the English were no longer in regular array. At this moment the French camp-followers and peasantry, who had wandered round the English rear, broke pillaging into the camp and stole the King’s crown, wardrobe, and Great Seal. The King, believing himself attacked from behind, while a superior force still remained unbroken on his front, issued the dread order to slaughter the prisoners. Then perished the flower of the French nobility, many of whom had yielded themselves to easy hopes of ransom. Only the most illustrious were spared. The desperate character of this act, and of the moment, supplies what defence can be found for its ferocity. It was not in fact a necessary recourse. The alarm in the rear was soon relieved; but not before the massacre was almost finished. The French third line quitted the field without attempting to renew the battle in any serious manner. Henry, who had declared at daybreak, “For me this day shall never England ransom pay,”2 now saw his path to Calais clear before him. But far more than that: he had decisively broken in open battle at odds of more than three to one the armed chivalry of France. In two or at most three hours he had trodden underfoot at once the corpses of the slain and the will-power of the French monarchy.

After asking the name of the neighbouring castle and ordering that the battle should be called Agincourt after it, Henry made his way to Calais, short of food, but unmolested by the still superior forces which the French had set on foot. Within five months of leaving England he returned to London, having, before all Europe, shattered the French power by a feat of arms which, however it may be tested, must be held unsurpassed. He rode in triumph through the streets of London with spoils and captives displayed to the delighted people. He himself wore a plain dress, and he refused to allow his “bruised helmet and bended sword” to be shown to the admiring crowd, “lest they should forget that the glory was due to God alone.” The victory of Agincourt made him the supreme figure in Europe.

When in 1416 the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund visited London in an effort to effect a peace he recognised Henry as King of France. But there followed long, costly campaigns and sieges which outran the financial resources of the Island and gradually cooled its martial ardour. A much larger expedition crossed the Channel in 1417. After a hard, long siege Caen was taken; and one by one every French stronghold in Normandy was reduced in successive years. After hideous massacres in Paris, led by the Burgundians, hot-headed supporters of the Dauphin murdered the Duke of Burgundy at Montereau in 1419, and by this deed sealed the alliance of Burgundy with England. Orleanist France was utterly defeated, not only in battle, but in the war. In May 1420, by the Treaty of Troyes, Charles VI recognised Henry as heir to the French kingdom upon his death and as Regent during his life. The English King undertook to govern with the aid of a Council of Frenchmen, and to preserve all ancient customs. Normandy was to be his in full sovereignty, but on his accession to the French throne would be reunited to France. He was accorded the title “King of England and Heir of France.” To implement and consolidate these triumphs he married Charles’s daughter Catherine, a comely princess, who bore him a son long to reign over impending English miseries.

“It was,” says Ranke, “a very extraordinary position which Henry V now occupied. The two great kingdoms, each of which by

Itself has earlier or later claimed to sway the world, were (without being fused into one) to remain united for ever under him and his successors. . . . Burgundy was bound to him by ties of blood and by hostility to a common foe.”3 He induced Queen Johanna of Naples to adopt his eldest brother as her son and heir. The King of Castile and the heir of Portugal were descended from his father’s sisters. Soon after his death the youngest of his brothers, Humphrey of Gloucester, married Jacqueline of Holland and Hainault, who possessed other lands as well. “The pedigrees of Southern and Western Europe alike met in the house of Lancaster, the head of which thus seemed to be the common head of all.” It seemed to need only a Crusade, a high, sacred common cause against the advancing Ottoman power, to anneal the bonds which might have united, for a space at least, all Europe under an Englishman. The renewal of strife between England and France consumed powerful contingents which could have been used in defending Christendom against the Turkish menace.

This was the boldest bid the Island ever made in Europe. Henry V was no feudal sovereign of the old type with a class interest which overrode social and territorial barriers. He was entirely national in his outlook: he was the first King to use the English language in his letters and his messages home from the front; his triumphs were gained by English troops; his policy was sustained by a Parliament that could claim to speak for the English people. For it was the union of the country gentry and the rising middle class of the towns, working with the common lawyers, that gave the English Parliament thus early a character and a destiny that the States-General of France and the Cortes of Castile were not to know. Henry stood, and with him his country, at the summit of the world. He was himself endowed with the highest attributes of manhood. “No sovereign,” says Stubbs, “who ever reigned has won from contemporary writers such a singular unison of praise. He was religious, pure in life, temperate, liberal, careful, and yet splendid, merciful, truthful, and honourable; ‘discreet in word, provident in counsel, prudent in judgment, modest in look, magnanimous in act’; a brilliant soldier, a sound diplomatist, an able organiser and consolidator of all forces at his command; the restorer of the English Navy, the founder of our military, international, and maritime law. A true Englishman, with all the greatnesses and none of the glaring faults of his Plantagenet ancestors.”

Ruthless he could also be on occasion, but the Chroniclers prefer to speak of his generosity and of how he made it a rule of his life to treat all men with consideration. He disdained in State business evasive or cryptic answers. “It is impossible” or “It shah be done” were the characteristic decisions which he gave. He was more deeply loved by his subjects of all classes than any King has been in England. Under him the English armies gained an ascendancy which for centuries was never seen again.

But glory was, as always, dearly bought. The imposing Empire of Henry V was hollow and false. Where Henry II had failed his successor could not win. When Henry V revived the English claims to France he opened the greatest tragedy in our medieval history. Agincourt was a glittering victory, but the wasteful and useless campaigns that followed more than outweighed its military and moral value, and the miserable, destroying century that ensued casts its black shadow upon Henry’s heroic triumph.

And there is also a sad underside to the brilliant life of England in these years. If Henry V united the nation against France he set it also upon the Lollards. We can see that the Lollards were regarded not only as heretics, but as what we should now call Christian Communists. They had secured as their leader Sir John Oldcastle, a warrior of renown. They threatened nothing less than a revolution in faith and property. Upon them all domestic hatreds were turned by a devout and credulous age. It seemed frightful beyond words that they should declare that the Host lifted in the Mass was a dead thing, “less than a toad or a spider.” Hostility was whetted by their policy of plundering the Church. Nor did the constancy of these martyrs to their convictions allay the public rage. As early as 1410 we have a strange, horrible scene, in which Henry, then Prince of Wales, was present at the execution of John Badby, a tailor of Worcestershire. He offered him a free pardon if he would recant. Badby refused and the faggots were lighted, but his piteous groans gave the Prince hope that he might still be converted. He ordered the fire to be extinguished, and again tempted the tortured victim with life, liberty, and a pension if he would but retract. But the tailor, with unconquerable constancy, called upon them to do their worst, and was burned to ashes, while the spectators marvelled alike at the Prince’s merciful nature and the tailor’s firm religious principles. Oldcastle, who, after a feeble insurrection in 1414, fled to the hills of Herefordshire, was captured at length, and suffered in his turn. These fearful obsessions weighed upon the age, and Henry, while King of the world, was but one of its slaves. This degradation lies about him and his times, and our contacts with his personal nobleness and prowess, though imperishable, are marred.

Fortune, which had bestowed upon the King all that could be dreamed of, could not afford to risk her handiwork in a long life. In the full tide of power and success he died at the end of August 1422 of a malady contracted in the field, probably dysentery, against which the medicine of those times could not make head. When he received the Sacrament and heard the penitential psalms, at the words “Build thou the walls of Jerusalem” he spoke, saying, “Good Lord, thou knowest that my intent has been and yet is, if I might live, to re-edify the walls of Jerusalem.” This was his dying thought. He died with his work unfinished. He had once more committed his country to the murderous dynastic war with France. He had been the instrument of the religious and social persecution of the Lollards. Perhaps if he had lived the normal span his power might have become the servant of his virtues and produced the harmonies and tolerances which mankind so often seeks in vain. But Death drew his scythe across these prospects. The gleaming King, cut off untimely, went to his tomb amid the lamentations of his people, and the crown passed to his son, an infant nine months old.

World History

World History