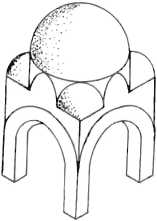

The main kinds of vaulting used by the Byzantines were as follows: the barrel vault (in essence a protracted arch), the cross-groined vault (two barrel vaults intersecting at a right angle), the dome upon a drum or rotunda, the domical vault or pendentive dome (in which the pendentives merge seamlessly with the cupola), the dome on pendentives, and the dome on squinches (Restle 1995).

A stone-built domical vault (in which the pendentives merge seamlessly with the cupola) is known already in the first century bce at the baths in Petra (McKenzie 1990: 51, pi. 76b). In the fourth and fifth centuries stone domes on squinches or pendentives are known in Asia Minor (Hill 1996: 46-7), and there is a possibility that the towers of certain stone-built churches in fifth-century Cilicia were crowned by stone domes on squinches or pendentives, although polygonal timber roofs are equally likely (Hill 1996: 45-6, 78-81, 155-60, 213-14). Stone domes of various types are found in the Tur Abdin in northern Mesopotamia (Bell 1982: 21, pis. 140, 142 (on squinches)) and at Binbirkilise in central Anatolia (Ramsay and Bell 1909: 441-6, figs. 42, 205 (on corbels), 87,339,342 (on pendentives), 308 (on squinches)); under their influence, several seventh-century churches in Armenia were crowned with a dome on squinches (Mango 1976:180-1,184). In Jerusalem, the square bays

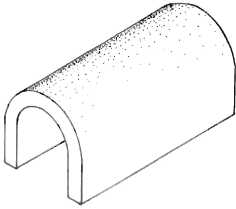

BARREL VAULT

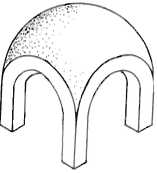

DOME ON PENDENTIVES

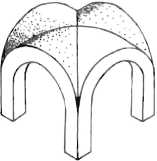

DOMICAL VAULT

CROSS-GROINED VAULT

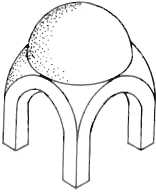

Fig. 1 Byzantine styles of vaulting

DOME ON ROTUNDA

DOME ON SQUINCHES

Of the Golden Gate are roofed with stone domes on pendentives (Mainstone 1975: 121, fig. 7.12). At Ravenna, Theoderic’s mausoleum is crowned by a low monolithic dome of Istrian stone, whose weight is estimated at over 230 tonnes, and whose saucer shape may have been calculated to avoid radial cracking (Deichmann 1974: 218-19; Curdc 1992: 32-5; Adam 1994:191).

In Ancient Rome, there had been a long tradition of concrete vaulting (Lancaster 2005), but in Roman Asia Minor, where the volcanic sands that gave the concrete of Rome its strength were generally not available, solid brick vaulting—a tradition inherited from Mespotamia and Egypt—had been the norm from at least the midsecond century ce. In brick-built vaults, the bricks might be either radially laid or pitched. The pitched brick technique, also adopted from the mud-brick architecture of Egypt and Mesopotamia, is attested as early as the second half of the third century in Asia Minor at Aspendos, and is known in the west in the rotunda at Thessalonike in the fourth (Ward-Perkins 1981: 89-95). It is a regular feature of Byzantine brickwork.

In Constantinople, large brick domes upon a rotunda or polygon must have been used from an early date in structures such as the imperial mausoleum (built either by Constantine or by Constantins), the rotundas at the Myrelaion (Naumann 1966) and the Hippodrome (Naumann 1965; Bardill 1997), the hexagon of Antiochos’ palace (Naumann and Belting 1966: figs. 6,7), the hexagon in Giilhane (Demangel and Mamboury 1939: 81-111), and the martyrium of Sts Karpos and Papylos (Schneider 1936:1-4). Smaller brick domes survive in the chambers of the polygonal towers of the early fifth-century Land Walls (Meyer-Plath and Schneider 1943* 31-2). A large-scale dome may have covered Constantine’s cathedral church of the Golden Octagon at Antioch-on-the-Orontes, which is known to have been a centralized building (Eusebios, VC 3.50); and a dome would certainly have crowned Jerusalem’s Anastasis Rotunda, which was erected beside the basilica on Golgotha by 348-50 if not during Constantine’s reign (Krautheimer 1986, 462-3 n. 45). Such domes should be seen as paving the way in Constantinople to experimentation with brick domes over polygonal or square bays, culminating in the spectacular dome on pendentives that crowns Hagia Sophia, which is over 31 metres in diameter (Mainstone 1988:126-7, 209-17; Taylor 1996).

Although brick was rarely used in Syria, on the church at Qasr ibn Wardan there was certainly a brick dome, which is notable in that the pendentives were not between the four main arches but contained within an octagonal drum (Butler 1929:168-9). A number of other brick vaults in Syria and Mesopotamia are known (Deichmann 1979: fig. 1). Notable among these is the cross-vault in the Praetorium at Zenobia (Halebiye) (Deichmann 1979: 501-2, pi. 167.1), which recalls those in the Constantinopolitan cisterns of the Binbirdirek and Yerebatan Sarayi, the bricks being arranged in concentric squares up to the crown of the vault. Brick domes on squinches and pendentives are also found in northern Mesopotamia (Bell 1982: 5, pis. 206,225).

The dome on squinches, familiar from stone-built architecture in Armenia (Maranci 2001: 86-97), was constructed in brick in eleventh-century churches in Constantinople (St George in the Mangana) and Greece (the katholikon of the Nea Moni on Chios and the katholikon of Hosios Loukas) (Mango 1973:130-2; Maranci 2001:129-31).

As in the earlier Roman concrete vaults of the Circus of Maxentius, the mausoleum of Helena, or the villa of the Gordians (Lancaster 2005: 68-85), hollow jars continued to be incorporated into vaults at their springing. The technique is found from the late fourth to early sixth centuries at Ravenna, for example in the domes of the Orthodox Baptistery, of S. Vitale, and the semi-dome of S. Apollinare Nuovo (Deichmann 1974: 24, figs. 12,18-21; 131, fig. 83; Deichmann 1976: 64-5, fig. 31; Storz 1984; Wilson 1992:117). Later examples occur in Constantinople in the substructures of St George in the Mangana, Kalenderhane Camii, Christ Pantokrator, and the south church of the Lips monastery (Ousterhout 1999: 229-30).

In parts of Syria and Jordan, mortared volcanic scoriae were used to create vaults and domes, such as the semi-domes in the exedras of both the cathedral at Bosra and St John’s at Jerash (Crowfoot 1941: 96, 98, 105; Deichmann 1979: pi. 159.1), the vault in the south baths at Bosra (Ward-Perkins 1981: 345-6; Crowfoot 1941: 106), and the sugar-loaf dome upon an octagonal drum of the church of St George at Zorah (Butler 1929:121-5; Ward-Perkins 1981:344). Further examples are noted by Deichmann at Antioch-on-the-Orontes, Bosra, Dura Europos, Jerash, and Philippopolis (1979: 476-7, 483, fig. 1).

Barrel vaults of either stone-faced mortared rubble or mortared rubble alone were used in the basilicas of Binbirkilise (Ramsay and Bell 1909: 437, figs. 8, 27 (stone-faced), 103 (mortared rubble)) and in early Armenian churches (Maranci 2001: 111-15). In the Tur ‘Abdin, one finds barrel vaults either completely in brick (Bell 1982: 45, pis. 164-5) or of several stone courses at the spring with brick over the crown (Bell 1982:10-11, pis. 242, 244). At Dura, there are fine examples of barrel vaults covering the cisterns, which are up to 25 m long and 4 m wide. These are constructed of mortared rubble alternating with brick bands (Deichmann 1979: 503-4, pl. 169.2).

A huge cross-groined vault, as was familiar from the roofing of the major thermal establishments in imperial Rome and the Basilica of Maxentius in the Roman Forum, was apparently used to crown the square tower of S. Lorenzo in Milan in the second half of the fourth century (Kleinbauer 1976).

The wooden dome of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem (Creswell 1969: 92-7) is a clear indicator that there must have been many wooden vaults, but little archaeological and textual evidence survives (Creswell 1969: 116-21). The archaeological evidence indicating that there was a wooden roof spanning the 27-m-wide octagon at Qal’at Si’man suggests that it was polygonal rather than domed. Chorikios suggests that a wooden vault existed in the church of St Sergios at Gaza, but, as is typical in the case of such descriptions, it is disputed as to whether he speaks of a dome over the nave or a semi-dome over the apse (Mango 1972: 70-1).

The development of pozzolanic mortar for vaulting meant that the Romans did not master the stone cross-vault. In Syria, however, the art of vaulting in stone reached a higher level of development because stone was generally the most easily available building material. It has been suggested that it was perhaps a Syrian architect who was responsible for the tomb of Theoderic in Ravenna, which is the only monument in the Italian peninsula with a stone cross-vault (Deichmann 1974: 215; Adam 1994:191).

World History

World History