These three themes combine to inform our current understanding of medieval Ireland’s economy and society. By 1100, these were in a state of quite radical transformation. Although once regarded as having had a devastating effect, the impact of the Viking incursions and subsequent settlement of the ninth and tenth centuries has now been qualified and revised into a more assimilative model in which the Hiberno-Norse contributed to, but did not cause, the profound changes already occurring in Irish society. While pre-Viking trade appears to have been primarily with Britain and north-west Europe, it does seem that Ireland became part of a northern trading network during the ninth and tenth centuries. But all the evidence of the extensive archaeological excavations of Viking Dublin points to a rapid restoration of the routes to south-west England and France, as the Vikings became assimilated into Irish society during the eleventh century. The material artefacts found in Viking Dublin were neither Viking nor Celtic nor Anglo-Saxon, but related rather to a common north-west European milieu. Thus Ireland was being integrated into that world long before the Anglo-Norman colonization of the late twelfth century.

It is now widely agreed that the key processes of change in Irish society between the ninth and the eleventh centuries concerned the emergence of a redistributive, hierarchical, rank society, which subsumed the previous system defined by reciprocity and kinship. A redistributive structure, which is based on clientship and defined by flows of goods towards dominant central places, is a prerequisite for urbanization in that it reflects the evolution of a social hierarchy based upon the power to control production. A class of peasant rentpayers probably emerged in Ireland as early as the ninth century, together with the concept of dynastic overlordship. The eleventh and twelfth centuries saw the development of lordships very similar to feudal kingdoms in Europe, essentially bounded embryonic states governed by kings who were sufficiently powerful to launch military campaigns and fortify their territories. The earliest indications of systematic incastellation in Ireland date to the very late tenth century, when Brian Boruma constructed a succession of fortresses in Munster. By the twelfth century, the Ua Briain kings of Thomond and the Ua Conchobair kings of Connacht are recorded as constructing networks of castles to consolidate their control over their respective kingdoms.

In concert with this transformation of secular society, the remarkably diverse and very secular Irish church was also being changed by twelfth-century reform, a process that began before the Anglo-Norman invasion but markedly accelerated after it (see chapter 22 in this volume). The creation of a parochial system was heavily influenced by the delimitation of the Anglo-Norman manorial structure, the boundaries of which it generally shared. Patronage by feudal lords lay at the heart of the acquisition of church lands and, by the later thirteenth century, there was little to distinguish the abbeys from the other great landowners of the age. As was the norm elsewhere in the feudal societies of north-west Europe, magnates of the church such as archbishops of Dublin, who held a whole succession of manors around the fringes of the city, were also great secular lords.

The Anglo-Norman soldiers who came to Ireland in 1169 were not embarked on a systematic conquest but rather were mercenaries enlisted by the deposed king of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, in an attempt to regain his territories. They were led by ambitious Welsh marcher lords such as Robert fitz Stephen and Richard fitz Gilbert de Clare, far better known as Strongbow. Giraldus Cambrensis sums up their motivations when he remarks of Strongbow that his name was greater than his prospects, that name, and not possessions, being his principal inheritance. To these freebooters, Ireland, situated beyond the immediate control of the English crown, offered opportunities for power, wealth, land and prestige likely to be denied to them in their homelands by the feudal laws of primogeniture. They took their chances and thus the initial Anglo-Norman colonization of Ireland was very much a question of individual enterprise and initiative. As O Corrain argues, Diarmait’s invitation inevitably become an invasion, while the initial Anglo-Norman colonization of Ireland, like most great changes in history, was its unforeseen and unplanned consequence.

The crown did become more systematically involved following Henry Il’s visit to Ireland in 1171-2, although the king’s intentions have been the subject of some debate. He was concerned perhaps that some Anglo-Norman barons were becoming too independent and powerful. Conversely it has been argued that, following the murder of Thomas a Becket, Henry was motivated by a desire to ingratiate himself with the papacy, which saw its opportunity to impose full Gregorian reform on Ireland. Given the absence of any central civil power, Henry regarded the church as the only effective institution to hold sway throughout the island. What is not in dispute is that Henry had received the homage of the hierarchy of the Irish church as well as that of the Gaelic-Irish kings and Anglo-Norman barons by the time he departed from Ireland in 1172. None the less, the tensions that ultimately were to ensure the intense territorial fragmentation of later medieval Ireland were already apparent from the outset of the Anglo-Norman colonization. By granting major lordships, while lacking the resources or inclination to conquer Ireland, the crown abrogated substantial powers, which often made individual barons remote from the mechanisms of government established in Dublin. However, these magnates also required the rewards and social prestige which the crown could confer and, to some extent, most were ‘royalist’. Consequently, Marie Therese Flanagan regards ‘improvisation’ as having been the defining characteristic of Anglo-Norman Ireland, Henry and his successors lacking the time, men, resources and control over the adventurer-settlers of Ireland to adopt any other strategy.

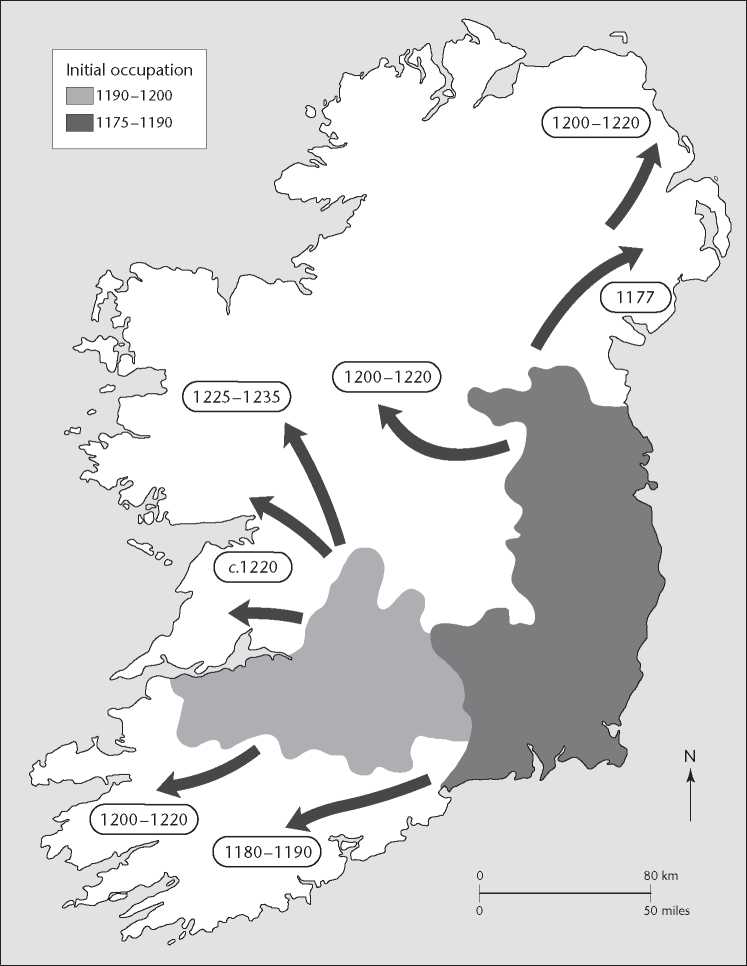

Adrian Empey regards the concept of lordship as simultaneously embracing the personal ties that mutually bound lord and vassal and the idea of a bounded territory in which the lord exercised his prerogatives. In a parallel fashion, the manor - the essential subdivision of the lordship and the focal point of the new social and economic order - was a military, economic, social and juridical institution, and a geographical unit. The boundaries of lordships and their internal subinfeudation were often identical to those of the pre-existing Gaelic-Irish kingdoms. One of the best examples is Henry II’s charter of 1172 granting Meath to Hugh de Lacy to hold as the Ua Mael Sechlainn kings of Midhe had before him. By the mid-thirteenth century, the Anglo-Normans had colonized some two-thirds of the island (map 8.1). In those areas beyond their direct imprint, including most of Ulster, much of the west coast, part of the central lowlands and almost all the uplands, a degree of Gaelic-Irish political autonomy was preserved, as was a social and economic system which, as we will see, was somewhat different to that of the colony. As Kenneth Nicholls states, however, the extant documentation of this society is so deficient and late that only a few deductions can be hazarded for the 150 years following the Anglo-Norman invasion. The spatial relationships between the two broad medieval cultures were complex, ambiguous and dynamic and never fully resolved, although the church and the economy provided powerful unifying bonds.

The initial Anglo-Norman settlements were often but not necessarily located at existing centres of power. This continuity could be no more than simple expediency, reflecting the extant distribution of resources and population and the need to redistribute land rapidly, or even an attempt to capture and replace the structures of Gaelic-Irish political power. Everywhere the Anglo-Normans embarked on a conscious process of incastellation throughout their lordships. Many early fortifications were earthwork mottes or ringworks but, from the beginning, major castles were built in stone, arguably symbolic of a commitment to the new lands and evidence of an intention to stay and transform them. Stone fortresses such as Trim and Carrickfergus were designed for defence but also to reflect the prestige of their lords and to act as the centres of administration in their respective fiefdoms.

The establishment of military hegemony over lordship and manor underpinned the subsequent development of the Anglo-Norman colonization. We know little about the demography of the Anglo-Norman colony or of the origins and numbers of migrants who settled on the Irish manors. Estimates of the medieval population of Ireland, c.1300, range from 400,000 to 800,000, although it is impossible to calculate the ratio of Anglo-Norman to Gaelic-Irish. Although the immigration of large numbers of peasants into thirteenth-century Ireland is an important factor demarcating its experience from that of England after the Norman Conquest of 1066, there is no evidence of the nobility using middlemen - the locatores of eastern Europe - to organize this movement. Hence, Adrian Empey regards Wales as being the best exemplar for Ireland, its Anglo-Norman colonization also being shaped by the requirements of a military aristocracy rather than the broad-based peasant movement characteristic of central and eastern Europe.

The manor was the basic unit of settlement throughout the Anglo-Norman colony. Anngret Simms and others have argued that the constraint of the pre-existing Gaelic-Irish network of townlands (the basic subdivision of land in Ireland, a townland was originally the holding of an extended family) pre-empted the formation of large villages on the Anglo-Norman manors of Ireland. This model holds that the demesne farm - the land retained by the lord of the manor - was run from the manorial centre while major free tenants held land independently in townlands of their own, thereby rendering settlement nucleation impracticable. It is possible that free tenants were also associated with the rectangular moated sites, which proliferated in the thirteenth century. The agricultural economy formed the basis of all production in Anglo-Norman Ireland, although its organization and the associated arrangement of field-

Map 8.1 The Anglo-Norman colonization of Ireland.

Systems remain seriously under-researched areas. Otway-Ruthven argued that the manorial lands were laid out in open-fields, while each social group among the tenants tended to hold land in separate parts of the manor. In particular, the betagii, the unfree Gaelic-Irish tenants who can be equated with the English villeins, retained specific areas of the manors, which were farmed on an indigenous infield-outfield system similar to the system known later as rundale. There is, however, little evidence to support the model of native betagh rundale and Norman three-field-systems, particularly as the analogy with an idealized, English midland field-system can no longer be sustained given that there was no single English regional model but, instead, innumerable variations arising from environmental differences and the vigour of social and economic change.

Whatever the organization of the manorial lands, the essential problem for feudal landholders was how to develop and maintain the rural economy. It is likely that the Anglo-Normans expanded and extended existing systems of agricultural production, not least because these were subject to the constraints of the physical environment. They colonized the fertile but fragmented grassland soils and controlled the two richest grain-growing areas in the island, which were located in the south-east along the Rivers Barrow and Nore and around the Boyne in the Lordship of Meath. Arable production seems to have been particularly significant up to 1300, although grazing was always important. Under medieval conditions arable land necessarily required some pasture for the livestock that was used in its cultivation and manuring, and meadowland to provide hay for winter fodder. Oats seem to have been the most important grain crop, followed closely by wheat with barley a poor third.

Cereal growing began to contract about 1300, partly because of changing patterns of agricultural output in Ireland, these being heavily influenced by the demands of the English market. During the thirteenth century, grain production had been bolstered by the system of purveyance for the royal armies. Growing resistance by merchants, resentful of the long delays that occurred in payment, combined with declining production in Irish agriculture to end purveyance in the 1320s. The decline in cereal production is also indicative of a succession of internal crises, which marked the first half of the fourteenth century in Ireland. Mary Lyons’s detailed study of the relationship between population, famine and plague concludes that the demographic base of the Anglo-Norman colony was probably substantially eroded in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. Famine occurred with increasing frequency after C.1270, and later the Great North European Famine coincided with the very considerable political instability and warfare within Ireland brought about by the Bruce invasion of 1315-18. Moreover, the early part of the fourteenth century seems to have been exceptionally wet. Thus Lyons emphasizes that the economic downturn in medieval Ireland occurred long before the first visitation of the Black Death in 1348-50. It is possible that the Anglo-Irish population could have been almost halved by the end of the fourteenth century because of plague, although Lyons believes that its impacts varied regionally, being most profound in Leinster and close to the ports.

In traditional medieval historiography, this half-century of crisis was regarded as having precipitated the final decline of the Anglo-Norman colony and thus provided one key element in the explanation of economic and social change after c.1300. The other was the notion of a Gaelic Revival or Resurgence, a concept that embraces both cultural and territorial dimensions in that it implied a return to Gaelic values and physical reconquest. Recent historiography, however, points to a more complex set of interactions and also to the conclusion that decline has been exaggerated. There is, however, minimal research into the type of structural transformation that occurred in later fourteenth-century England, and we know little of the ways in which feudal social and property relationships were being dissolved in Ireland or of the consequences for landholding and settlement. Rather the debate on the later fourteenth century is dominated by the revision of the Gaelic Resurgence. The idea of a static Gaelic-Irish society acting as a repository for age-old traditions is now widely regarded as the conscious creation of fourteenth-century scholars who provided the intellectual justification for the late medieval Gaelic-Irish lords. Moreover, although the reasons are not adequately researched, there was an economic revival in the later fourteenth century, a recovery best symbolized by the first appearance of rural and urban tower houses. These tall, rectilinear keep buildings were probably largely built by a new class of freeholding lesser lords, both Gaelic and Anglo-Irish. Although possessing some limited defensive merit, they are now seen as essentially domestic structures, while the availability of the financial resources sufficient to construct an estimated 7,000 tower houses in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries fits ill with the concept of an economic crisis or a Gaelic Revival.

Contemporary explanations portray a more complex interaction between Gaelic-and Anglo-Irish Ireland at this time and also a very marked geographical variation in those relationships. Robin Frame maintains that the dichotomy was real enough but sees it as representing two poles or limits, rather than defining the reality of life for much of the population. Large swathes of Ireland remained in the hands of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, although not necessarily within the remit of the Dublin government. The area under its control contracted during the first half of the fifteenth century to the Pale, the fortified but still relatively permeable frontier that extended around the four counties of Louth, Meath, Dublin and Kildare. Elsewhere political fragmentation and a loss of central government control produced a mosaic of autonomous and semi-autonomous Gaelic-Irish and Anglo-Irish lordships. W. J. Smyth cogently sums up the fifteenth century as the fusion of a number of relatively powerful port-centred economic regions with the administrative-political superstructures of the great lordships. Beyond these core territories lay rural-based, less stratified and generally (though not invariably) smaller political lordships. The hybridization of this society is recorded in the finely differentiated cultural geography that can be reclaimed from the patterns of naming of places and people. Given the lack of central government records, documentation is very deficient but it is probable that a semblance of the manorial economy continued, while economic differences between Gael and Gall became less marked. Certainly, as the evidence of urbanization also attests, there is little to suggest that the political decline of the English crown in Ireland in the fifteenth century was necessarily matched by any real transformation in the socio-economic structure.

World History

World History