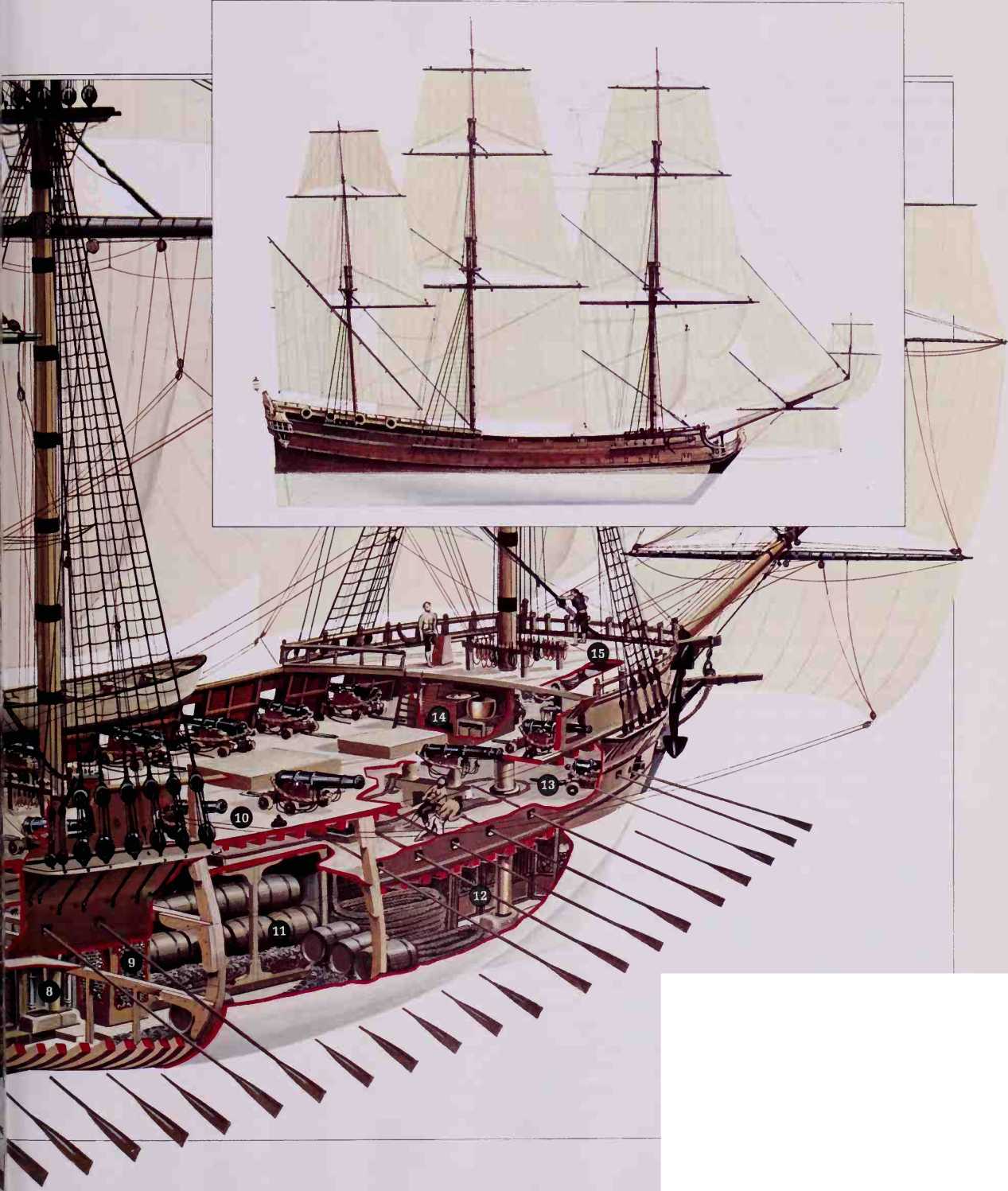

When she was launched in 1695 at the Thames River shipyard of Deptford, Captain William Kidd’s ship Adventure Galley was the latest in fighting vessels. Designed for speed, maneuverability and firepower, the. Adventure Galley was equalK’ suited as the pri'ateer for which she was intended or as the pirate ship she soon became.

She was a hybrid vessel, combining a modern hull and sail rig with the ancient concept of oar power: under full sail, with 3,200 square yards of canvas, she could make a swift 14 knots: without wind but with two or three pirates straining at each of her 46 oars, she could still move at three knots, een though she was heavy for a ship of her size (since she was built for combat she had larger, more closely spaced ribs than a merchantman).

Aside from the captain’s cabin, in which councils of war were held, and a nearby cubby for the first mate, the interior of the. Adventure GoIIey was spartan in the extreme. There were no crew quarters as such: at night the 150 or so men crammed into her 124-foot hull curled up wherever they could: they relieved themselves by clambering onto the bowsprit. There was no galley—just a gigantic stewpot and a bricked-in hearth used only in calm weather and located far from the powder stores. Fire was the terror of every crew. o smoking or open flame was permitted belowdecks: light for the powder room emanated from a lantern shining through a heavy glass window in the tin-lined lightroom.

In the hold, the shot locker, with its six tonsof shot for the 12-pounder cannon. and the huge water casks, each weighing a ton. were located amidships to help ballast the ship. Hoisting the stores aboard was very difficult: it took 40 men to work the giant capstan: a major job. such as raising the 3,000-pound anchor with its 6,000 pounds of cable, could take an hour or more.

1 GREAT CABIN

2. QUARTER-DECK

3. FIRST MATE'S CABIN

4 MAGAZINE LIGHTROOM

5 MAGAZINE

6 PROVISIONS

7. CAPSTAN

8. SHIP'S PUMPS

9. SHOT

10. UPPER DECK

14. GALLEY

15. FO'C'S'LE DECK

11. WATERCASKS 12 SHIP'S STORES

13. LOWER DECK

Ward along the coast. There was great excitement on board the/d'en-fure Galley at the prospect of a big prize, but when she came up within a league of the merchantman. Kidd saw she was flying English colors.

William Moore, the gunner on the/dvenfure Galley, proposed that they plunder the vessel anyway. Kidd refused to consider it. “I dare not do such a thing." he said.

"We may do it." cried Moore. "We are beggars already.”

The English ship proved to be theLoyoI Gaptain. outward bound from Madras to Surat. All her papers were in order and Kidd let her go. This infuriated his crew. A few brought out their small arms, but Kidd faced them down. He had not come here to take any Englishmen or lawful traders. "If you desert my ship," Kidd told them, "you shall never come aboard again, and I will force you into Bombay, and 1 will carry you before some of the Council there.”

The mutiny fizzled out. But not the rancor. On October 30, 1697, Captain Kidd and gunner Moore had their final confrontation. According to a teen-age deck hand named Hugh Parrott, the quarrel began as Moore, who had been ill, sat grinding a chisel on deck. When the captain appeared, Moore shouted at him:

"Captain, I could have put you in the way to have taken the ship, and have never been the worse for it.”

According to Parrott, this put Kidd "in a passion”—so much so that the lad took refuge belowdecks. Other hands remained up top. Moore continued to upbraid the captain.

"You have brought us to ruin, and we are desolate,” he railed.

"Have I brought you to ruin?” cried Kidd. "I have not done an ill thing to ruin you. You are a saucy fellow to say those words.”

According to a sailor named Palmer, Kidd did not say "saucy fellow” but "lousy dog.” To which gunner Moore screamed, "If I am a lousy dog, you have made me so!”

All agree about what happened next. The captain, now beside himself with fury, yelled: "Have I ruined you. you dog?” And with that he seized an ironbound bucket (worth eightpence of lawful English money, his prosecutors were to point out later) and crashed it against Moore’s head, a little above the right ear.

The gunner’s shipmates carried Moore below as the captain cried out after them: "Damn him! He is a villain!”

Moore died the next day of a fractured skull.

A stunned and sullen peace descended on the wretched Adventure Galley. Weeks went by. Then at the end of November, four leagues from Calicut, they sighted a sail. Kidd bore down on the vessel and ordered French colors to be run up—a ruse to make the stranger do the same. Sure enough, the ship hoisted a French flag in return. The ship was the Maiden, bound for Surat with a cargo of cotton, quilts, sugar and two horses. Her captain and two officers aboard were Dutchmen; all of the seamen were Moors. The Dutch skipper explained to Kidd that his ship was Moorish, and he also produced a French pass—indicating that she sailed under French auspices. Kidd evidently believed that this French pass made the Maiden a legitimate prize. "By God, have I catched you?” he cried. "You are a free prize to England!”

The Sceptre, a 36-gun vessel belonging to the British East India Company, gave Kidd's Adventure Galley a scorching baptism o//Ire in 1697 when the pirate captain cut into its convoy of Moorish treasure ships. "Had not our ship happened to hove been in theircompany, he had certainly plundered all the headmost ships of all their wealth," surmised the captain of the Sceptre.

Kidd turned the Moors loose in the longboat, and with the connivance of the Dutchmen, he sold the cargo ashore for cash and gold, which he shared out among his men—an act in direct contravention of his contract. He renamed the captured ship November after the month of her capture, and took her along with a prize crew on board.

This was the first money the crew had touched since the Adventure Galley had left London nearly two years before. But it was not money they were entitled to. True, the Dutch captain had handed Kidd a French pass. But the pass was meaningless, since shipowners routinely obtained a pass from every nation operating in the area, and the captain had a number of other passes in his possession. The November was actually Indian-owned, and though it was customary for privateers to take prizes on even flimsier pretexts, according to the strict letter of the law Kidd had committed piracy.

Something must have clicked in Kidd’s tortured mind at this stage in his voyage. It would seem he had finally decided that the lowly men who shared his leaking vessel were a more immediate threat than the few great men to whom he owed allegiance in Whitehall half a world away— and that, though forced to do wrong, he remained morally right. For he was now to commit piracy again and again.

Three days after Christmas 1697, Kidd seized a Moorish ketch off the Malabar Coast, and took some tubs of candy and a sack of coffee. Twelve days later he plundered a Portuguese ship of a quantity of East India Company goods, and some gunpowder, opium, rice, iron, beeswax and butter. So far Kidd’s plunder added up to little more than the contents of an Indian general store. But on January 30,1698, he took his most fateful prize. The Quedah Merchant was a 500-ton merchantman belonging to Armenian owners and commanded by an English captain named Wright. Outward bound from Bengal to Surat with a rich cargo of silks, muslins, sugar, iron, saltpeter, guns and gold coin, she was making heavy weather off the Indian coast 10 leagues north of Cochin when she was spotted from the lookout of the Adventure Galley. Crowding on sail, Kidd pursued her for four hours. When he finally came up with her he fired across her bows and hoisted his French flag. Kidd ordered the merchantman’s master to come on board the Adventure Galley, yet it was not Captain Wright who arrived, but an old French gunner posing as the captain. Whereupon, to the Frenchman’s great surprise, Kidd ran up the English flag and claimed the vessel as a prize.

And so it seemed at first. The old gunner handed him a pass signed by the Director General of the Royal French East India Company in Bengal only a fortnight before. But as with the November, the fact that the Quedah Merchant carried a French pass did not make her a French ship. Her Armenian owners were on board and offered to ransom the ship for nearly ?3,000, an offer Kidd scorned as insufficient. Instead, he sold some cargo onshore for ?10,000, divided the proceeds among the crew, and sailed to Madagascar with both the November and the Quedah Merchant as prizes. It was only when they had been sailing for five or six days that the true identity of the Quedah Merchant’s master was revealed. Captain Wright was brought before Kidd and Kidd was horrified to discover that he had unwittingly broken even his own rules and captured an Englishman's command. Only now, perhaps, did he become fully aware of the extent to which he had compromised himself. He summoned the crew and addressed them from the quarter-deck.

“The taking of this ship would make a great noise in England,” he told them. He proposed that they should hand the Quedah Merchant back to Captain Wright. But his crew would not hear of it, and so the three ships continued on their course.

On April Fool’s Day, 1698, the tiny fleet finally reached Madagascar. Ironically, the harbor they entered was the pirates’ haven of St. Mary’s Island. And for the first time in his two-year cruise, the pirate catcher was confronted with a pirate ship.

Riding at anchor in St. Mary’s was the Mocha Frigate, a captured East Indiaman, whose captain, Robert Culliford, had turned pirate after serving on a privateer. Even now Kidd was torn between his duty and his destiny. Although he had gone pirate, he still dreamed of catching pirates. He urged his men to seize the Mocha. They howled with derision. They told him they would rather fire 10 shots at him than one at the pirates, and began to share out the spoils of the Quedah Merchant. Curi-

IVifcJ with rage, Kidd hurls a bucket at his mutinous gunner, Wittiam Moore, os they cruise off the coast of Indio. This melodramatic 19th Century engraving cost Kidd os vicious blackguard, Moore os his innocent victim. Eyewitnesses never agreed upon who wos to hlome, but Moore’s death provoked o murderchorge that eventually sent Kidd to the gallows.

Ously, it was a privateer share-cut, for Kidd got a full 40 shares of the plunder, not the usual two shares accorded a pirate captain. After that, however, all but 13 of his men deserted to Culliford, including Robert Bradinham and Joseph Palmer, who later testified for the prosecution at Kidd’s trial, sealing his terrible fate. They sacked and burned the November. Next, they clambered all over Kidd’s remaining two ships, stripping them of guns, small arms, powder, shot, anchors, cables, surgeon’s chests and anything else that took their fancy. They burned Kidd’s log, threatened several times to murder him, and almost certainly would have done so had he not barricaded himself in his cabin. There, Kidd was totally trapped and finally compromised.

It is not recorded how long Kidd remained in his cabin. But at some juncture during those sweaty tropical weeks in St. Mary’s, he capitulated to the pirate captain Culliford. “Before I would do you any harm,” he finally swore, “I would have my soul fry in hell-fire.”

Kidd’s surrender had the desired effect: his life was spared, along with that of his brother-in-law (a sick man since the epidemic 15 months before] and the handful of men who had stayed loyal to him, while the Quedah Merchant was allowed to remain afloat with a fair share of booty still on board. In mid-June, Culliford’s Mocha, her crew grown to 130 and her guns up to 40 at Kidd’s expense, sailed out into the Indian Ocean and Kidd began to prepare for his return to England.

The first voyage of the Adventure Galley had proved to be her last. Half full of water and resting on a sandbar in the shallows, she could sail no farther. Kidd had her stripped and her hull burned for its iron. He then fitted out the bulky Quedah Merchant for the voyage home and began the difficult task of recruiting a crew from the nautical flotsam drifting around the islands. He had plenty of time, for he had to wait five months before the northeast monsoons could blow him around the Cape. At last, on November 15,1698, the Quedah Merchant weighed anchor in St. Mary’s harbor. Kidd seems to have had no qualms about the wisdom of returning home. His family awaited him; he had property to attend to; and he undoubtedly believed that he still had enough cargo in goods, jewels, silver and gold to square accounts with his powerful sponsors.

Captain Kidd was only three days out from St. Mary’s when the East India Company wrote a letter from its headquarters in Surat to the Lords Justices in London in which a number of extreme accusations of piracy were leveled against him. The charges fell on receptive ears. To Kidd’s high-placed backers—Lord Somers, now Lord High Chancellor; Lord Orford, First Lord of the Admiralty; Lord Shrewsbury, Lord Chief Justice; and Lord Romney, Privy Councillor—it had long been obvious that their opportunist effort at merchant-venturing was a dismal flop. There had been no decrease in the incidents of piracy. As for Kidd, there had been no news but uncomplimentary rumor. Now, it seemed, their worst fears were confirmed.

The response of the Lords Justices was vigorous and immediate. They ordered a Naval squadron, on the point of sailing to the Indian Ocean, to capture Kidd. At the same time, the Admiralty dispatched a circular letter to the governors of the American colonies ordering them to apprehend Kidd so that “he, and his Associates, be prosecuted with the utmost

Rigour of the Law.” Finally, with the object of isolating Kidd, a free pardon was offered to every pirate east of the Cape except Kidd and two other captains, one of whom was Henry Every.

The news spread like smoke throughout England. A first-class political scandal erupted as Tory opposition politicians ripped into the four Whig Lords who had sent Kidd off in the Adventure Galley. William Kidd had become an archcriminal guilty of the most unspeakable crimes, and in the eyes of the government, the East India Company, the press and the general public he was found guilty before he had set foot on land, or so much as uttered a word.

Such was the situation when, early in April 1699. Kidd made his landfall at Anguilla in the Leeward Islands and sent his boat ashore. It returned with devastating news. In every port of the colonies, in virtually every quarter of the known world. Kidd and his crew had been declared pirates, to be arrested on sight.

For four hours the Quedah Merchant rode at anchor. Some of the men wanted to scuttle the ship against a reef and then disperse rather than sail into a port that was under English control. But Kidd would not run. He had been away too long. He was too old for an outlaw’s life of exile. He would see the thing through. He had powerful friends in London and New York and he had the two French passes from the vessels he had plundered, so he was not a pirate—or so he believed. He decided to make for New York, where he reckoned he could count on the protection of the new governor. Lord Bellomont. one of the first supporters of the Adventure Galley cruise.

As Kidd sailed north, it was obvious to all that the Quedah Merchant had to be replaced. She was too big and distinctive to avoid detection, too barnacled and seaworn to outsail pursuit. In the Mona Passage on the southeast coast of Hispaniola, they came upon a becalmed trading sloop, the Antonio. The Antonio was neat, fast and anonymous. Kidd bought her from her owner-skipper for 3,000 pieces of eight and moored the Quedah Merchant under guard up the Higuey River in Hispaniola. He transferred much of the Quedah Merchant booty, including his own personal treasure—gold bars, gold dust, silver plate, precious and semiprecious stones, fine silks—to the Antonio. And then with a crew of 12, the rest opting to remain, he sailed boldly for New York.

On June 10, the Antonio rounded Long Island and anchored in Oyster Bay. Kidd had been away nearly three years. He had voyaged more than 42,000 miles, a distance greater than the circumference of the earth. The ship in which he had sailed was a ruined hulk on a tropic island; all but a handful of his crew were dead or pirating in the Eastern Seas. And he was an outlaw. Kidd’s desperate gamble for life and freedom now entered its most critical stage. Everything depended on winning over Lord Bellomont, and to do this Kidd pinned his hopes on his two French passes. From Oyster Bay, therefore, Kidd sent a letter to an old friend and neighbor of his in New York, a lawyer named James Emmott, asking him to come out to the ship. Emmott arrived in a day or two, spoke with Kidd, then hastened to Boston, where Bellomont had his headquarters. Emmott saw Bellomont late on the night of June 13, proposed that he should grant Kidd a pardon and handed him the French passes.

Bellomont, who had received unequivocal orders to arrest Kidd, was in a difficult position. His own career was in the balance, and he dared not make any move that would cause Kidd to flee. On June 19, he sent a letter to Kidd by the hand of the Boston postmaster, Duncan Campbell, a friend of Kidd, in which he inveigled the captain into port with a masterpiece of double-dealing.

“I have advised with His Majesty’s Council and shewed them this letter,” wrote Bellomont, ‘‘and they are of the opinion, that if you can be so clear as you (or Mr. Emmott for you) have said, then you may safely come hither. And I make no manner of doubt but to obtain the King’s pardon for you, and for those few men you have left who I understand, have been faithful to you, and refused as well as you to dishonour the Commission you have from England. I assure you on my word and honor, I will perform nicely what I have promised.”

Confided Bellomont in a letter to London: ‘‘Menacing him had not been the way to invite him hither, but rather wheedling.”

Kidd, overconfident, perhaps, as a result of his exchanges with Bellomont, now played his hand badly. Instead of bringing in his cargo for condemnation by Admiralty court, he appeared to regard it as his private property. To Bellomont’s wife he unwisely sent as a ‘‘gift” a number of baubles, including a magnificent enameled box with four diamonds set in gold. Left and right he handed out largess, hoping to ingratiate himself with everyone. Yet he was not so foolish as to discard all precautions. Sloops came and went, carrying away treasure to friends for safekeeping. Finally, in the orchard of Gardiner’s Island at the eastern tip of Long Island, he buried the bulk of his swag—including a chest containing gems and a box of gold—and duly obtained a receipt from the proprietor of the place, John Gardiner. Captain Kidd’s treasure was now cunningly dispersed in a number of widely scattered caches. If he went free, he could pick them up later; if he was taken in custody, they would be a useful bargaining point.

Kidd’s wife, Sarah, and his two daughters joined Kidd on board the Antonio at Block Island. The girls had been only three and four years of age when he left; he had missed nearly half their childhood. After such a long separation it was a heartfelt reunion, given added poignancy by the terrible circumstances of the occasion. Sarah Kidd had suffered through the hue and cry over her husband for months; she could hardly have shared his optimism as to the outcome. The family stayed on board all the way to Boston. They were to enjoy only two weeks together before being parted forever.

The Kidd family landed in Boston on July 2,1699, and took rooms in a boardinghouse. Kidd unwisely sent another bribe to the Governor’s wife. Lady Bellomont, this time ?l,000 worth of gold bars sewed up in a green silk bag. She immediately sent them back. The next day, Kidd was interviewed by Bellomont, sitting in Council in his house. The Captain was coldly asked for a detailed account of his movements since leaving England. He replied, somewhat truculently, that his crew had destroyed his log. The Governor and Council ordered him to prepare a report. Kidd either could not or would not. Finally on July 6, all patience at an end, the Council voted for Kidd’s immediate arrest. The police searched high

World History

World History