There has been eonsiderable controversy over the location of Ipswich Castle and even whether a castle existed at all. The latter we can prove fairly convincingly, but the former will always be open to debate. There are simply no remains to be found.

There are three possible contenders for the castle location, the first being Castle Hill. This must surely have been too far away from the town centre. It does contain the site of a fourth-century Roman villa, but there arc no remains of a medieval castle.

For the second site, I concur with Keith Wade in his article in the Historical Atlas of Suffolk. He says that the castle stood just above the junction of Elm Street and Museum Street. This could then, by extension, make St Mary at Elms Church the site of the original chapel for the castle. (There is some Norman masonry in the church although the majority of the building is 15th-century.) Its location seems logical. The main town was located within the ramparts. On this site, the castle overlooked the bulk of the population and could also sec potential trouble on the River Orwell.

As for the third contender, this is claimed for the site of St Mary Ic Tower church. This is a possibility, but it is not an ideal position. The mottc would have had to be extremely high to sec over the ramparts.

The main threat was not local rebellion but the risk of Viking invasion. For this reason the ramparts were built between 650 and 850 and continually strengthened, the last time in 1205. These were ditches topped with a palisade of pointed stakes and, later, flint rubble. The Viking ships could approach Ipswich quickly, the river being used like a motorway, allowing a fast getaway.

Ipswich was attacked by Vikings at least twice before the Norman conquest. In 991 Olaf landed with 93 ships, and in 1010 Ipswich suffered at the hands of Thorkcl, becoming for a time part of the Scandinavian empire.

In 1069, there was a final raid on Ipswich by the Vikings when Sweyn of Denmark arrived. This was repelled after a concerted attack by Norman soldiers under Roger Bigod, Robert Mallet and Ralph Wader. This had been a bad attack and for the next twenty years Ipswich remained almost desolate, witli only no traders in 1086 and at least 328 homes laid waste. There is however another version of this story. It is said that the Normans used the excuse of the Viking attack as an opportunity to take revenge on Ipswich for the killing of William the Conqueror’s horse by Earl Gyrth at the Battle of Hastings.

Earl Gyrth was King Harold’s brother and had been lord of the manor of Ipswich before 1066. Although this seems a rather fanciful story there may be some grains of truth. Could it be that the Normans became rather over-zealous in their defence of the town and allowed their soldiers free rein?

By around the year iioi, a castle appears to have been erected by Roger Bigod when work was being carried out at Framlingham. It seems likely that stone was used from the outset on a simple motte-and-bailcy design, probably with a square keep.

The castle was attacked and besieged by King Stephen in It'll and the small garrison quickly capitulated. Stephen had given Hugh Bigod the Earldom of Norfolk and Suffolk in 1140 in the hope of retaining his loyalty, but Hugh was not to be relied on and sided with Henry of Anjou. So, from 1153, Ipswich was a royal castle. By 1154, Henry of Anjou was King Henry II and Stephen was dead.

The Bigod family again changed their loyalty, for in 1173 Hugh Bigod had sided with Henry of Anjou, son of Henry II. On 24th September a Flemish mercenary army under the leadership of Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, landed at Walton. Hugh was to welcome them at Framlingham (see p. 45).

Beaumont’s army proceeded to Ipswich, took the castle and awaited reinforcements. From Ipswich the party travelled to Haughley, successfully attacking the castle. The rebellious army was eventually stopped at Fornham St Genevieve near Bury St Edmunds.

Henry’s revenge on Bigod was swift and an attack was made on Bigod at Bungay. Bigod surrendered and only avoided execution by paying an enormous fine. Bigod’s castles at Bungay and Framlingham were ordered to be razed to the ground under the supervision of the king’s engineer, Alnodus. At the same time Henry ordered the destruction of Ipswich, Walton and Haughley. This left the king with only two castles in Suffolk: Eye and the newly constructed Orford.

It seems strange that Henry ordered the destruction of his own castles at this time. Probably he considered their maintenance and modernisation too expensive. They must also have been very badly damaged. Perhaps also Henry was afraid that they might have been used against him in the future.

Lidgate (seven miles south-east of Newmarket) was the birthplace in c. l375 of John Lydgate, the poet monk of Bury St Edmunds Abbey. The church stands within some earthworks which are known as ‘King John’s Castle’.

This is an unusual setting, rectangular in construction with one of the baileys now being used as the churchyard to St Mary’s church. The castle was gone when the church was built around 1250. It is probable that the church was built as an extension to the original chapel and reused building materials from the castle. The walls to the churchyard on the northern side also appear to contain recycled earlier material.

The same bailey is shared with 2, Tinker’s Close. The cutting behind this house is almost certainly not original and was dug out to provide access to the land behind, probably when the house was

Built in the 1890s. There is also an outline impression of a building measuring 43 x 23 feet (13 x 7 m) on the raised part of the garden.

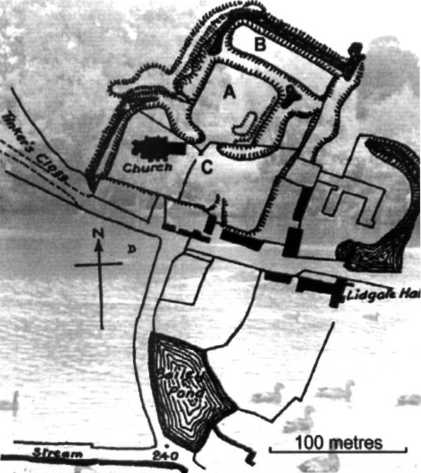

There appear to have been three baileys to the castle. The area marked A on the plan was the site of the main building. This area was divided from C by a flint wall which partially remains on the south-western side. This wall may originally have contained the gatehouse to the main bailey. There appears to have been a square building on the site. B is an extra bailey or court.

C would have contained a chapel, stables, storage buildings and kitchen. Finally we have D which is now filled with housing on a slope down to what would have been the bailey pond. In addition to this pond there is a second on the easterly side by some farm buildings. These would have provided fish for use in the castle.

The site takes advantage of naturally rising ground. The surrounding ditches are extremely impressive and of massive proportions. The ditches are dry, but the fosses on the western side now contain water. The ones on the north-east and south-east would have been filled with water from a brook.

This was certainly an iron age hill fort, reused by the Normans. The Iron Age was between 800 Bc and AD 43 when England was invaded by the Romans. It was constructed for three reasons: first to protect travellers on the Icknield Way (there was a similar fortification at Kirtling in Cambridgeshire); secondly, to protect the Devil’s Ditch or Dyke, the barrier built by the local Iceni tribe, some three miles away; finally, it would have protected the community who would have lived at the top of the hill. We know the site was reused during the Roman occupation as Roman bricks have been found in the churchyard.

The castle or fortified dwelling is said to have been built by Reynold sans Nase who was given Lidgatc by William I for distinguished service at the Battle of Hastings. His name was recorded on a stone tablet in Battle Abbey. (The stones were lost at the dissolution of the monasteries but the names had been copied.) Ownership had been passed to William de Vateville, a Norman knight who was an under-tenant of Reginald the Bretton by 1086. He also had holdings in Hargrave and Lackford. In 1110, Reginald de Scanceler gave Lidgate into the care of the monks of Bury St Edmunds as he was about to depart for the crusades. He never returned and ownership remained in the hands of the abbey.

The castle was no doubt strengthened during the civil war between King Stephen and Queen Matilda under the direction of Maurice de Windsor who was a steward of Bury Abbey. By 1166 it had been leased to William de Hastynges. His name is recorded in a survey of knight’s fees returned to the royal exchequer by order of Henry II for Bury St Edmunds Abbey. Hastynges also had knight’s fees at Blunham in Bedfordshire and at West Harling,

Tibenham and Giss-ing in Norfolk. Each tenant-in-chief, such as the Abbot of Bury St Edmunds, was expected to provide fighting men for the king.

This avoided the need for the king to maintain a permanent army. Hastynges was one of these knights under the abbot.

Bury St Edmunds’ quota of knights was forty. They had to give forty days service when demanded by the king or their tenant in chief, at their own expense. This could be anything from active service to guard duty. Often the service was replaced by a money payment of about ?40 a year, known as scutage. The knight could also sell his services elsewhere.

William’s son, John dc Hastynges, became a hereditary steward for the abbey at Lidgatc. A later John Hastings appears as Earl of Pembroke in 1376.

I am not sure why Lidgate has the title ‘King John’s Castle’. The term is first recorded in the 17th century. King John came to Suffolk at least twice in his reign. The first time was immediately after his coronation in 1199. He and his court enjoyed the hospitality of the abbey in Bury despite the fact that John was not liked by Abbot Samson. Samson was however a great politician and made sure that no breach of allegiance could be levied at himself or his monks.

It must have been a very different John who came to Suffolk in March 1216 to quell Roger Bigod and take Framlingham as part of his campaign in the Barons’ War. In the previous year he had been forced to sign Magna Carta and it was Samson who had allowed the barons to draw it up at their meeting in the abbey. Samson was conveniently absent at the time of the meeting, but blame must have been attached to him, for John sent a contingent of soldiers to damage Lidgate at this time, both as an attack on Hastynges, who had supported the barons at Runnymede, and as a snub to the abbey, whose castle it was. The castle destroyed, the church was built in the 1250s.

Lidgate had a sizeable population in medieval times. In 1086 its population was around 170, and this had risen to 350 in the early 14th century. If the castle stopped being used by 1250, the maintained castle must have been due to the fact that that it had its own market, which we know was taking place every Thursday in 1279. At the first official census in 1801, the population was 323 - not even as much as it had been before the Black Death of 1349-50.

It is a shame there is now so little left of the castle. Even archaeological excavations would likely prove unfruitful, for it is said that most of the castle foundations were dug up in the 19th century to provide hard core for local roads. At least we have a clear outline of the baileys and some walls, which narrowly escaped when bombs were dropped in the fields north-west of the site in World War 2.

One final appeal. Please could the church authorities remove the ivy covering the wall at the east of the church? This deserves preservation and exposure.

World History

World History