These started in the 1560s, when Shane O’Neill began to equip his men with arque-busses, impress large numbers of unfree peasants, and hire extra Scots mercenaries from overseas. By 1569 musketeers and mailed pikemen had appeared in Irish armies.

The ‘New Scots’

These were a new wave of Scots mercenaries, mainly recruited from the Western Isles. They were probably bare-legged (hence their nickname of ‘Redshanks’) and generally dressed like other Highlanders of the period. Organised in companies with a paper strength of 100, they included some cavalry and ‘shot’ with firearms, pikemen, and halberdiers, as well as men with the more traditional Highland weapons, longbows and two-handed claymores. They were found in most Irish armies in the second half of the 16th Century, though they had most of the usual faults of mercenaries and came quite expensive (each man got one bullock per quarter for pay and two for food!).

Tyrone’s army

Hugh O’Neil, Earl of Tyrone, created the first really effective Irish army of the period, using as a nucleus Irish infantry he had kindly offered to train for Queen Elizabeth, and senior officers who had served in the English or Spanish armies. He raised 6,000 disciplined Irish foot, organised in companies of 100 and regiments probably 500 strong, with drums, bagpipes and colours.

And armed with matchlock muskets and pikes (the musket bullets were made out of lead imported from England, ostensibly to re-roof O’Neil’s castle of Dungannon). There were at least two musketeers to every pikeman, probably more.

Tyrone also reorganised the cavalry, equipping at least 300 'in the English fashion’ with light lances and (presumably) stirrups; however, his cavalry, though good at harassing tactics, still could not stand up to the English in the open.

Generally, gallowgiasses had become pikemen, kern musketeers, and dress and armour was probably little changed, though one of O’Neil’s regiments wore red coats (probably his original troops for English service), and his men were said to have plenty of ‘graven murrions’ (morions).

On the flanks of his ‘regular’ forces, numbers of skirmishers with the older types of weapon operated, and there were also ‘New Scots’, including Tyrone’s own bodyguard of 200 musketeers.

Tyrone normally used harassing tactics in difficult country, but at the disastrous battle of Kinsale his forces drew up in the open in three large tercio-style blocks.

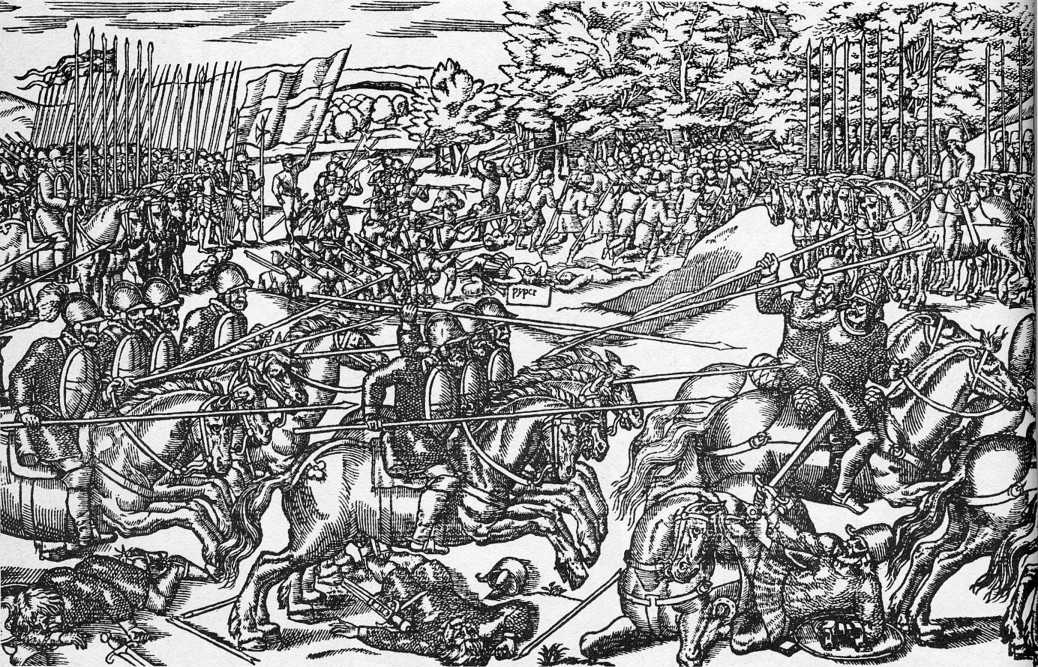

Another Derrick print from the same source showing the English (on left) defeating the Irish. In the foreground 'Northern Horse’ in mail charge the typical Irish cavalry who are very well depicted (including their method of using spears). In the background a 'pyper' lies dead, while axe-armed Gallowgiasses run away from English arquebusiers (British Library).

11

Like the Swiss, the Scots provided a steady flow of mercenaries to richer nations, serving with distinction, most notably in French, Dutch and Swedish armies, where they provided both complete regiments (including part of the French Royal Flousehold) and many distinguished commanders. However, we are here concerned with actual Scottish armies of the period, and their service was confined to the British Isles.

In the 16th Century there was a continuous conflict of raid, counter-raid and minor battle on the Border, punctuated by the great clashes of Flodden (1514) and Pinkie (1547), both Scots defeats, plus internal conflict in the later part of the century, involving the expulsion of French forces with English aid. In the 17th Century the Scots played a notable part in the Civil Wars, raising both the grimly efficient armies of the Covenant, which fought in all three Kingdoms, and the dashing Royalist army of Montrose (in whom Scotland produced arguably the greatest general of the period).

World History

World History