Constructed several cathedrals in England. Durham, one of the best examples of the Norman style, is a massive structure capable of inspiring wonhip but also of withstanding siege. Normans favored geometric designs for their arches. French versions of Romanesque architecture tended to have more elaborate exterior and interior carvings, such as those that can be seen today at Vezelay and Autun. The French also added small chapels in the apse area for private worship. In Sicily, elements of Moslem architecture were added to the arches, making them appear less weighty.

As the laity contributed more to the building of their parish churches and cathedrals, they demanded more from their clergy. They wanted the clergy to know the liturgy (the rites used for pubhc worship), to be able to instmct them, and to remain unmarried and lead exemplary hves. The quality of the clergy did improve. In the spirit of Cluny, the clergy wanted to remove themselves from the control of the ruling ehte, so that they could regulate their own ranks. Most important, of course, was liberating the papacy from the control of the emperors. Ever since Charlemagne’s rule, the emperors had claimed the right to reform the papacy when it became embroiled in local fights. Henry III of Germany was acting on the same tradition when he set up a reform pope in Rome.

To gain its freedom, the papacy needed to develop a way of electing its successors without outside influence. The man credited with working out the details of papal election was a Cluniac monk named Hildebrand, an Itahan who had moved into the Church hierarchy in Rome. He developed

Lasonry ceilings for Romanesque churches were either barrel vaults or cross vaults (groin vaults). Barrel vaults looked like half of a barrel or half of a cylinder of masonry perched on the supporting masonry walls. Cross vaults were composed of two half barrel vaults intersecting at a right angle. A series of these vaults formed the ceiling. The weight was concentrated at the four comers of the

Vault and the two groins. Cross-vaults had the advantage of adding some height and allowing for an arch that could provide space for a clerestory window, which let light in at the ceiling. Cross vaults were well suited for the aisles of a church because the wall of the nave and the outside wall could hold them up. However, the bigger expanse of the nave needed heavier, oblong vaults, and the weight of their

Heavy masonry required large piers to hold up each comer. Clerestory windows were minimal in the nave area. Sometimes wedge-shaped buttresses (supports) were used on the exterior of churches to hold up the masonry. Romanesque churches tended to be rather low and dark because the walls, piers, pillars, and, sometimes, masonry buttresses had to be very thick in order to hold up the ceiling.

Durham Cathedral is one of the most powerful examples of the Romanesque style. It has a massive, austere quality that represented both the piety of the Cluniac reform movement and the substantial conquest of the Normans in England.

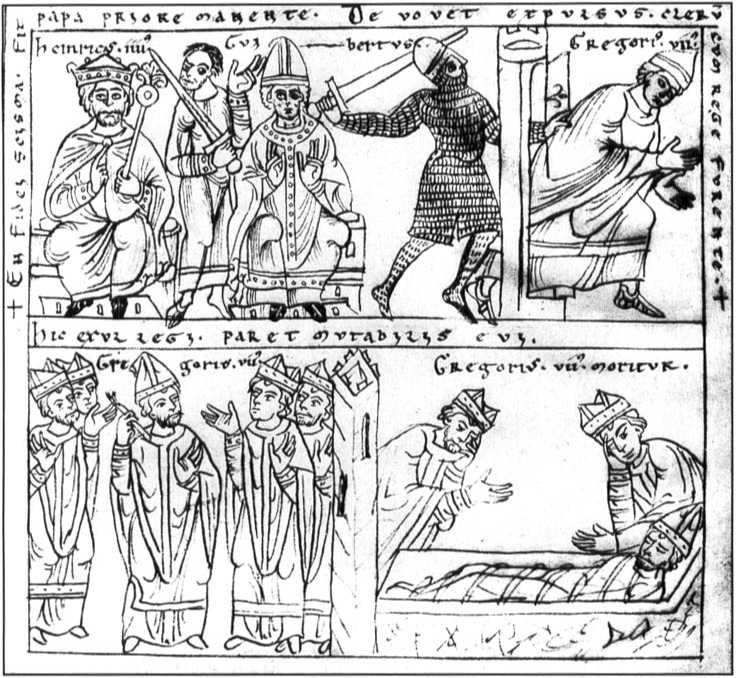

The struggle between Emperor Henry VI and Pope Gregory VII showed the tensions between the secular rulers of European monarchies and the power of the pope. In the famous fight between Henry and Gregory, each used his most powerful weapons. The pope used his spiritual power to excommunicate Henry in the first round, but Henry appeared as a penitent and had it removed. Later Henry used force of arms to set up an antipope, Guibertus, and expel Gregory from Rome. Gregory again excommunicated Henry, but the pope died soon afterwards in exile.

An electoral system called the College of Cardinals. In his plan the pope was to be elected by the most important clergy in Rome, that is, by the bishops, priests, and deacons of the churches in Rome and its surrounding countryside. The plan was an adaptation of the old custom of having the priests attached to a bishopric (or district) elect the new bishop. The College of Cardinals, which stiU exists, was later enlarged to represent all of the clergy by giving some of the archbishops and important ecclesiastical ofScials outside of Rome the tide of Cardinal so that they could vote. Hildebrand’s plan removed the emperor entirely from the process of electing a new pope. The first election went smoothly because Henry III had died, and his son, Henry IV (1056—1106), was onlyaboy and too young to interfere.

In 1073 Hildebrand himselfbecame Pope Gregory VII (1073—1085), but notthrough an election by the College of Cardinals. He was so popular in Rome that the clergy and populace ahke proclaimed him pope. Emperor Henry IV went along with Hildebrand’s elevation to the papacy because he was trying to estabhsh control over his rebellious German nobles.

Contemporaries described Gregory as a small man with a weak voice, but a strong vision of what the papacy should be. He claimed that the mission of the popes was to be the voice of St. Peter on earth and argued that, by the doctrine of the Petrine Succession, the pope was accountable to St. Peter and to God for the sins of humans. If an emperor sinned, the pope had a duty to call even him to account. In Gregory’s eyes, Henry IV had become a sinner because he continued to appoint bishops and abbots in Germany and to invest them with the symbols of their spiritual office—the bishop’s crook (stall) and ring. Investiture by a layman such as the emperor, as Gregory saw it, was unacceptable. From the early days of the church, monks customarily elected their abbots and the clergy elected their bishops—a principle that Gregory had invoked in creating his system for papal elections.

Henry IV had learned the hard realities of politics as a young boy. His mother had acted as regent, ruling in his stead while he was too young to do so, but during this time he became the virtual prisoner of the Bishop of Cologne. After freeing himself from these influences when he came of age, he began an active campaign to form his own power base. Realizing that he needed a wealthy region under his control, he se-

Lected Saxony, in part because it had silver mines. By 1075 he was successful in his campaign and feeling flush with impending victory.

By the same year, however, Pope Gregory VII was also feeling powerful enough to strike at the heart of lay investiture. Although Gregory was adamandy opposed to lay rulers selecting abbots and bishops, he recognized that ecclesiastical authorities might hold fiefs from a lay ruler, and he would permit them to receive those from a monarch, but he would not permit lay ralers to appoint ecclesiastical officers or invest them with the spiritual symbols of that office. In 1075 Gregory wrote several letters to Henry—calling him “beloved son”—in which he praised the emperor for not selling ecclesiastical offices and for upholding the principle of unmarried clergy. But he then attacked Henry for appointing bishops.

In one letter his address moved beyond a firm remonstrance; “Gregory, bishop, servant of God’s servants, to King Henry, greeting and the apostolic benediction— but with the understanding that he obeys the Apostolic See as becomes a Christian King.” He went on to stress his own spiritual power over Henry, “considering and weighing carefully to how strict a judge we must render an account of the stewardship committed to us by St. Peter, prince of the Apostles, we hesitated to send you the apostolic benediction.” Gregory was angry that Henry was appointing and investing bishops in both Germany and Italy against the papal edict and threatened him with excommunication (expulsion from the Church) if he continued to do so.

In 1076 Henry responded in a letter to his bishops. He called Gregory “not pope but false monk” and referred to Gregory’s own assumption of the papal throne as a usurpation because he was neither appointed by the king nor elected by the College of Cardinals. The salutation of one of his letters to Gregory reads, “Henry, King not by usurpation, but by the pious ordination of God.” Henry argued that he too had a sacred trust from God because ofhis consecration during the coronation ceremony. In his estimation, a monarch had a duty to God to cleanse the Church of a false pope. He rallied the bishops of Germany and Italy, who were loyal to him, and with their support closed his letter with the statement; “I, Henry, King by the grace of God, together with all our bishops, say unto you; Descend! Descend!” He was asking that the pope abdicate because ofhis false election.

Gregory realized that he could make no headway with the bishops that Henry had appointed in northern Italy and Germany, so he appealed to the German lay lords. They had resented Henry IV’s conquest of Saxony, and distrusted his plans to curtail their own independence. They were quite willing to listen to Pope Gregory’s suggestion that they rebel against their feudal overlord if he were excommunicated. Excommunication meant that a Christian was not allowed to participate in Holy Communion, but its ramifications went far beyond this religious ceremony. It also dissolved all feudal bonds of loyalty and forbade anyone from serving the excommunicated former member of the Church. In other words, excommunication put the offender outside of the community of believers. If Henry were excommunicated, the German nobles were released from aU feudal vows and could select anyone they wanted as their ruler.

Gregory excommunicated Henry in 1076. The German nobles immediately met and declared that, if Gregory did not revoke the excommunication order within one year, they would depose Henry. Gregory’s triumph was short-lived, however. Because Henry could find no loyal supporters among his nobility, he made a trip to Italy in January 1077 to waylay the pope, who was on his way to a meeting with the German nobility.

At Canossa in the Alps, Henry appeared before the walls of the castle in which the pope stayed, standing barefoot and clad in the rough wool garments of a repentant sinner. After the penitent king had stood in the winter cold and snow for three days, the pope finally relented. As he wrote to the German nobility, Henry “ceased not with many tears to beseech the apostolic help and comfort until aU who were present or who had heard the story were so moved by pity and compassion that they pleaded his cause with prayers and tears. AU marveled at our unwonted severity, and some even cried out that we were showing, not the seriousness of apostolic authority, but rather the cmelty of a savage tyrant.” As pope, Gregory could not refuse absolution to a sincere penitent, so the excommunication order was lifted.

Henry regrouped his power and in 1084 marched into Rome and selected a new pope. Gregory died in exile in 1085, reportedly exclaiming; “I have loved righteousness and hated iniquity; therefore

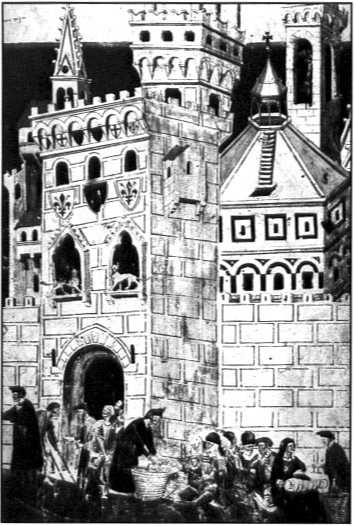

In Florence and other cities, the grain supply was crucial for the survival of the population, so the city regulated it. When grain was scarce, the poor and indigent who did not contribute to the economy of the city were evicted. When the city had abundant grain, officials distributed it liberally to the poor (right).

I die in exile.” But Henry did not triumph, either. Papal reform was by now too strong a movement for the emperors to control, and future popes continued to pressure Henry. While Henry was engaged in Italy, the German nobles again rebelled and supported Henry’s son against him. In 1122, at the Concordat of Worms, the Church was able to persuade his son, Henry V, to agree that only the clergy could invest the bishops with the symbols of their ofEce and that the emperor could not appoint bishops and abbots. But the bestowing of fiefs remained the right of a king or an emperor.

The papacy was not the only institution that reestablished itself in the late 11th century. The surplus of grain and the restoration ofpeace also allowed trade to flourish once again. Both peasants and nobles had surplus grain to sell and, therefore, money to buy practical items such as plowshares as well as luxury goods such as silks and ribbons, and spices to make their bland foods taste more interesting.

With the revival of trade and crafts, towns became an important part of the European landscape, just as they had been during the Roman period. Lords were so interested in attractingpeople to their towns that they offered peasants freedom from serfdom if they migrated. Other serfs took advantage of town laws that promised freedom to those who managed to live for a year and a day in town without their former masters claiming them. “Town air breathed free” is how they put it at the time.

Towns flourished throughout Europe, but none as much as those in Italy, where Venice, Genoa, Pisa, Milan, and Florence became major trading and industrial centers. Milan was known for its fine armor and its control of the overland trade with Germany. Venice, Pisa, and Genoa rivaled each other for their overseas trade in the Mediterranean and even across the Atlantic to countries including France, England, and the Low Countries. As townspeople prospered, they also sought freedom from kings and bishops so they could govern themselves and set their own rules of trade, government, and citizenship. Towns came to be governed by the merchants who dealt in luxury items and bulk shipments. The merchant class, in contrast to the nobility, enjoyed wealth derived from trade as opposed to land. Furthermore, the merchants needed goods to trade overseas. This demand encouraged artisans to produce high-quality cloth, art, and other products that would be valuable in trade. Peasants, who were also enjoying new prosperity because crop yields were improving, wanted to purchase better shoes, plows, tools, and pottery. Town markets and trades flourished, and so did the artisans.

The growing population moved into previously unsettled parts of Europe. As village populations became too large for their old sites, lords who held forests and swamps urged their serfs to clear the trees and drain the fens. To encourage them to take on this extra work, the lords offered serfs better terms and freedom from the servile duties they performed in return for their land on established manors. The new settlements adopted place-names that are still in use. Some of them were named for nearby settlements; for example, Little Horewood was a new settlement whose population came from Great Horewood.

Others had names that indicated a new foundation, such as Newcasde or Villeneuve (literally, New City in French).

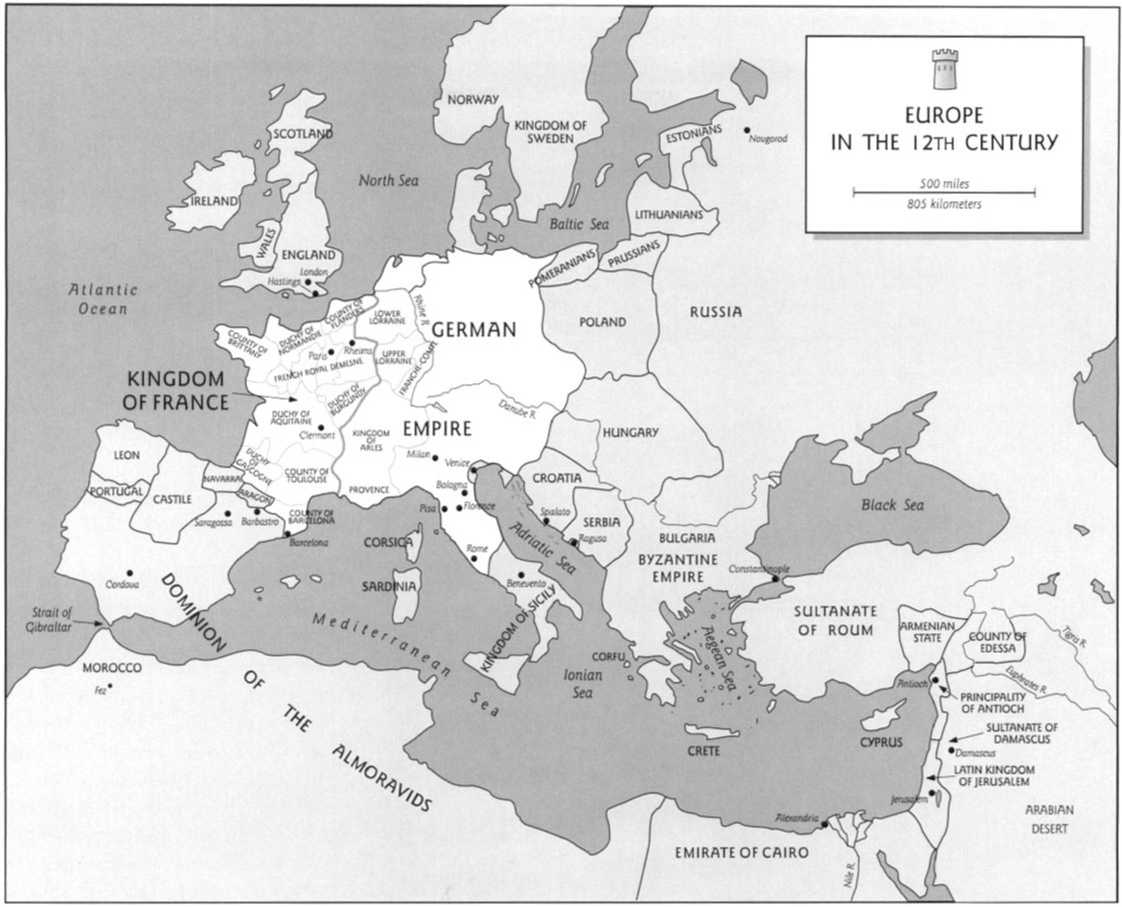

During this period, Netherlanders began to settle the marshes bordering the North Sea, establishing a system of dikes and windmills to drain these areas. The German emperors also conquered more land in the Slavic east in an expansion called the drang nach Qsten (drive to the east). They encouraged people in the heavdy populated areas of the Low Countries to move east and settle along the Baltic Sea and in Hungary and Bohemia. Just as in the United States during the 18th and 19th centuries the call to the adventurous was “Go West, Young Man,” in the 11th and 12th centuries, agents of German lords recmited serfs to go east and settle the new lands, bringing with them their technology ofplowing and draining fens.

If the peasant population was expanding both within the old territories and in newly conquered lands, the nobility was growing at an even faster pace. Noble mothers had a better diet than peasant mothers and produced children who were more likely to survive the dangers of childhood. The sizable family of a minor noble, Tancred de HauteviUe in Normandy, serves as a notable example of the circumstances of this large and aggressive group. He had 12 sons; five by his first wife and seven by his second. Because only one son could inherit the small ancestral lands, the others set out to seek their fortunes.

Three of the brothers—William Iron-Arm, Humphrey, and Drogo—

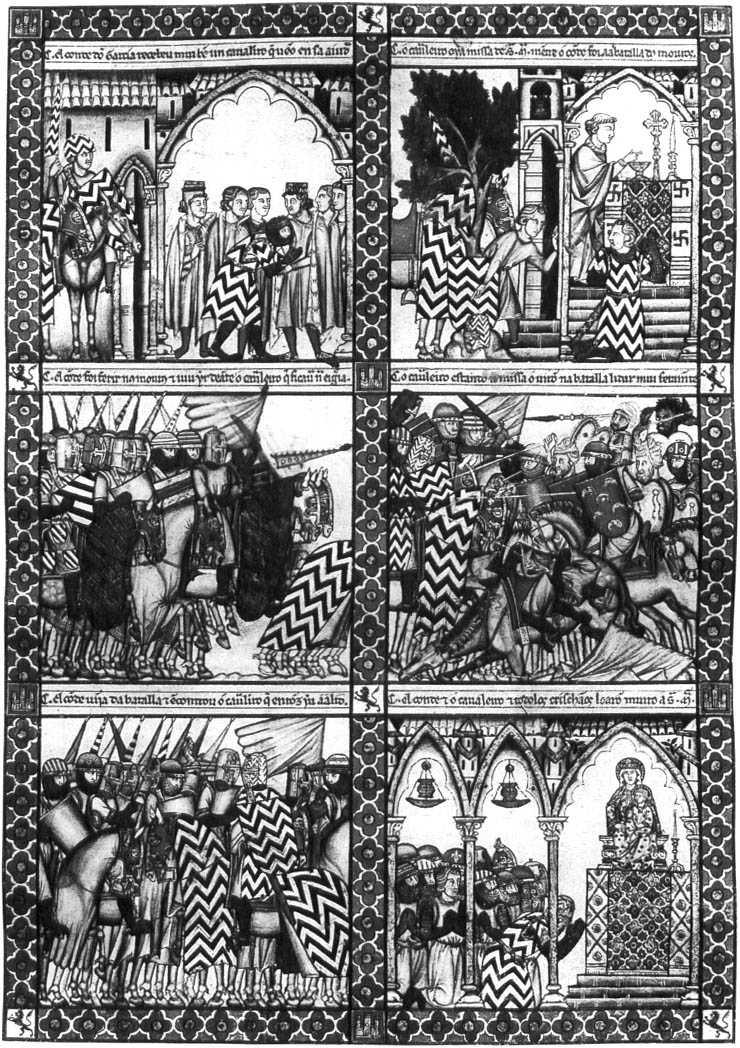

The Reconquista in Spain was part of the armed expansion of Europe in the i 1th and 12th centuries. The knights who sought their fortunes taking land from the Arabs and from each other viewed their wafare as a holy endeavor. A century after the events, a Spanish king who was also a crusader commissioned a book that showed the blessing of the troops before battle (top), the final victory of the Christians (center and bottom left), and a ceremony of thanksgiving for victor)’ before the Virgin and Child (bottom right).

Became warriors, sometimes acting as mercenaries and sometimes as bandits. During their pilgrimage to Jerusalem, they discovered that Sicily and southern Italy were fine places to practice their skills ofwarfare. The Arabs and Greeks who were fighting in these places were both willing to hire mercenaries. Soon the remaining de HauteviUe brothers had joined their kin and began carving out their own kingdoms rather than fighting for local factions. The halDbrother of WiUiam, Robert Guiscard (“the Fox” or “the Sly”), managed to conquer southern Italy and receive papal

Recognition as mler of the territory. His brother, Roger, captured Sicily and held it with papal approval by 1072. The brothers established a Norman kingdom in these two areas similar to the organized state that William the Conqueror had established in England.

Otheryounger sons of the nobility sought their fortunes in Spain by fighting against the Moslems there and carving out principalities. This fight became known as the Reconquista (reconquest) and was portrayed in the epic poem El Cid. The poem’s hero is based on a historical figure, Rodrigo Diaz, a Castilian noble who is born in about 1043. (His nickname, “el Cid,” means “lord” in Arabic.) In the poem, Diaz is a champion of the Christian faith. In reahty he was an opportunist who fought both Christians and Moslems, plundering both churches and mosques. By the early 12th century, Moslem control in Spain started to crumble, and the kingdoms of Aragon, Castile, and even Portugal began to expand.

During this period, the Arab world began experiencing reverses that would lead to its decline. While the French and Norman nobility were creating separate kingdoms in Sicily and Spain where the Arabs had previously ruled, the Seljuk Turks (a nomadic tribe that had converted to Islam) were making major conquests in the east. The Turks conquered Baghdad and moved west, where they defeated the Byzantine army and acquired Anatolia (part of modern Turkey), which they called the sultanate of Roum (an adaptation of“Rome”). Jemsa-lem and other areas of the Christian and

Jewish heritage came under the Turks’ control. Thus, when western Christians began to make extended pilgrimages to the Holy Land, they were greeted at inns and shrines not by the tolerant Arabs, but by the Turks, a group newly converted to Islam. Pilgrimage thus became more difficult and much more dangerous, and the native Greek Christian population complained to the pilgrims of persecution.

Relations between the Greek-speaking church in Byzantium and the Latin-speaking church in Rome also were strained. Although both parties believed that they were part of the same Christian church, the Roman Church, flexing its muscles during the reform movement, sought to dominate the patriarch ofConstantinople. The “Great Schism” of 1054 was the culmination of a number of clashes over the centuries. Controversies had arisen over such issues as the use of the Roman or Cyrillic alphabet among the Slavs, the wording of the Nicene Creed, the question of whether Christians should use two fingers or three to cross themselves, and the position of the pope in Rome as the titular leader of Christianity. These tensions led to a split between the two branches of the Church.

The increasing strength and belligerence of the European nobility and the papacy, together with the Turkish threat to Constantinople, led to an explosive clash of cultures called the Crusades. Literally, the word crusade meant “pilgrimage,” but the pilgrims were armed men from Europe who sought to retake the area around Jemsalem and any other rich territory that they could conquer, including the Byzantine Empire. While the ideal of crusading— to make Jerusalem a Christian city—lived on for centuries, many crusaders simply wanted to gain territory.

A volatile combination of interests, ambitions, and religious feeling gave rise to the first crusade. Pilgrims complained that they risked their lives going to Jerusalem, and that the Greek Christians, even though they were erring in their ways, were in grave danger of being killed. The merchants of Italian towns maintained that they were being ill-treated in Constantinople because of the schism and that trading in the former Byzantine and Arab territories had become increasingly dangerous. The economy of the Italian towns was suffering as a consequence. The Byzantine Emperor, Alexius Comnenus, wrote to the pope in consternation after a defeat suffered by the Byzantine army and asked that he send mercenaries, perhaps some of those fierce and footloose Normans. In return for such help, the emperor hinted that he would mend the schism by investing Rome with greater power than that of the patriarch of Constantinople.

The pope at the time. Urban II, held a council of French clergy and nobility at Clermont in 1095. There he preached a sermon that was a stirring call to arms to liberate the Holy Land. Addressing the French laity, he flattered them by praising their fame as warriors and called on them to avenge the Christians in the east. He noted that the Turks, followers of Muhammad,

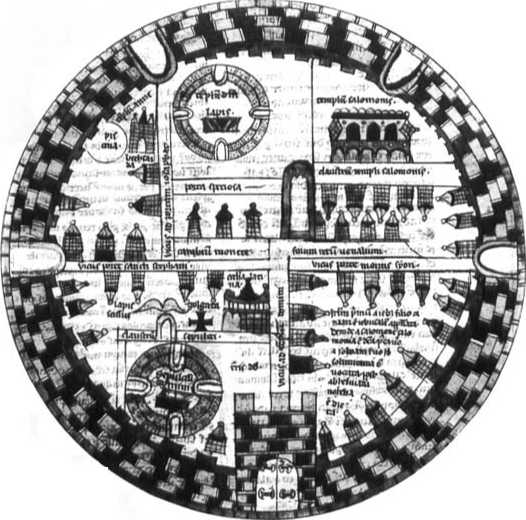

The liberation of Jemsalem from the Turks became the goal of the Crusaders. A map of the city drawn at the time of the Crusades showed the city wall with its five gates. The three major religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, all had their sacred structures in the city: the Temple of Solomon, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, and the Dome of the Rock.

THE FLOWERINB OF MEDIEVAL EUROPE • 79

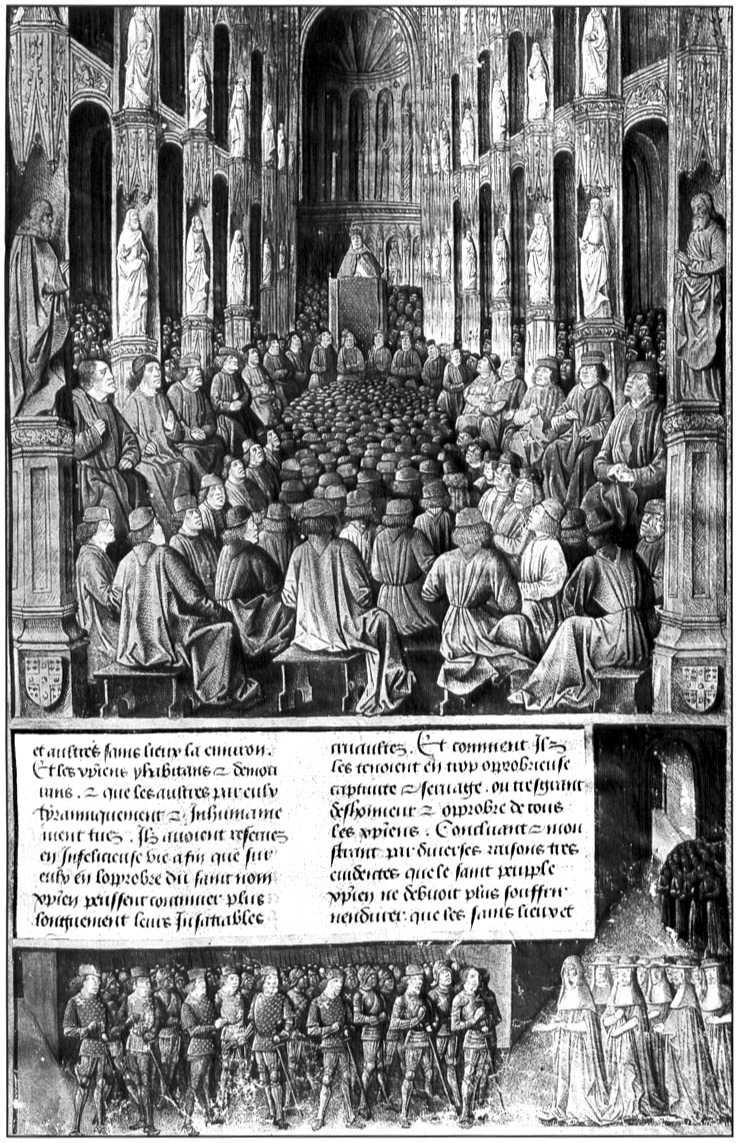

Pope Urban II met with the French nobility at Cleremont in 1095 and gave a stirring sermon calling upon his audience to recapture the Holy Sepulcher from the Turks, relieve the Byzantine Empire from the threat of annihilation, and enrich themselves by conquering fiefs for themselves in the biblical land of milk and honey. He called upon them to undertake a glorious holy war—which became the First Crusade.

Had killed Christians, destroyed churches, and dismembered the Greek empire. The Franks could liberate the Holy Sepulcher (the tomb in which Jesus had been buried) and aid the Greeks. The pope also alluded to the overpopulation of France; “This land which you inhabit, shut in on all sides by the seas and surrounded by the mountain peaks, is too narrow for your large population.” He pointed out that instead of fighting one another for land, they could go to the

Holy Land, the traditional land of milk and honey, and carve out estates there. For those who went, he promised remission of their sins so that they would go to heaven, for this was to be a glorious pilgrimage.

The audience responded enthusiastically, crying out “Dieu le veut!” (“God wills it!”). But Urban quickly reahzed that too much enthusiasm would not raise an army but a rabble. He cautioned that “we neither command nor advise that the old or feeble, or those incapable of bearing arms, undertake this journey. Nor ought women to set out at all without their husbands, or brothers, or legal guardians. Let the rich aid the needy; and according to their wealth let them take with them experienced soldiers.” Clergymen were not to go without the consent of their bishops.

Urban had, indeed, anticipated the problems that might arise. He and Emperor Alexius Comnenus needed an army of knights under the direction of a western king or at least a duke. But the pope’s first appeal inspired a mob of second sons, peasants, poor knights, and members of the clergy. Persuading the nobility to join up took more time. Finally, the Duke of Normandy (Robert, son of William the Conqueror); Count Raymond ofToulouse; Bohemund, son of Robert Guiscard; and several other French nobles agreed to go on the crusade.

While the main army of nobles and knights took time to organize themselves, amass supplies, and negotiate with Itafian merchants for ships, the popular crusade set off by foot across Europe. It was led by an impoverished knight, Walter the Penniless, and a preacher, Peter the Hermit. Their followers believed that the year 1100 would bring a second coming of Christ, and they wanted to be in Jerusalem when this happened. They also believed that the walls of Jerusalem would come tumbling down like those of Jericho, when they marched around them and blew their horns. Some people argued that they did not even need to go to the Holy Land to fight infidels; they could do just as well by attacking Jews in Europe. The first pogroms—in which Jews were rounded up, robbed, killed, and burned—occurred in Cologne. Most of the popular crusade, however, headed on through Hungary and the Balkans. The crusaders also believed that, as an army of God, the local inhabitants should feed them. When this charity was not forthcoming, they stole food. When they finally arrived at Constantinople, the emperor was so disgusted with them that he forced them to camp outside the city. Even so, they committed petty thefts and harassed the local population. Finally, the emperor agreed to ferry them over the Bospoms. There the Turks attacked them, and most were killed. Peter the Hermit, however, managed to return to Constantinople.

In the meantime, the main body of crusaders assembled in Constantinople. Relations between Emperor Alexius and the westerners were not cordial. A remarkable account of the Greek viewpoint was written by Alexius’s daughter, Anna Comnena. Anna claimed that the crusaders could not be trusted: “There were among the Latins such men as Bohemund and his fellow counselors, who, eager to obtain the Roman Empire for themselves, had been looking with avarice upon it for a long time.” Anna was right about Bohemund. She described an incident in which her father greeted Bohemund and invited him to a feast. Knowing that Bohemund would be suspicious of this, Anna’s father had his cooks bring raw meat to his guest and told Bohemund to have his own cooks prepare it if he preferred. With a great gesture of liberality, Bohemund divided up the cooked food and gave it to his followers, but did not take any for himself The next day he asked them if they were feeHng well or if the meal had been poisoned. They were all well. Anna concluded: “Such a man was Bohemund. Never, indeed, have 1 seen a man so dishonest. In everything, in his words as well as his deeds, he never chose the right path.”

After numerous squabbles between the cmsaders and the Greeks, Alexius and the leaders of the cmsade reached an agreement. Alexius would supply the cmsaders with the provisions necessary for their warfare, and in return the crusaders would dehver to him the cities of Asia Minor, which the Byzantine Empire had lost to the Turks. The emperor would also continue to supply the cmsaders with food and drink. The first town the cmsaders captured was Nicaea. Anna wrote that they did not, however, turn over the city as promised, but forced Alexius to pay for the city once again.

The cmsaders’ real test came at the siege of Antioch in 1098. Alexius stopped their supplies just as they attacked the city. The situation became desperate as food ran short

Medieval bestiaries described animals, both real and fictional. Sometimes the animals were characters in fables written to teach the readers moral lessons about covetousness and other sins. Other times the descriptions are of animal behavior, habitats, and origins of names.

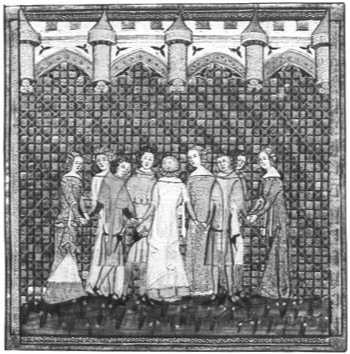

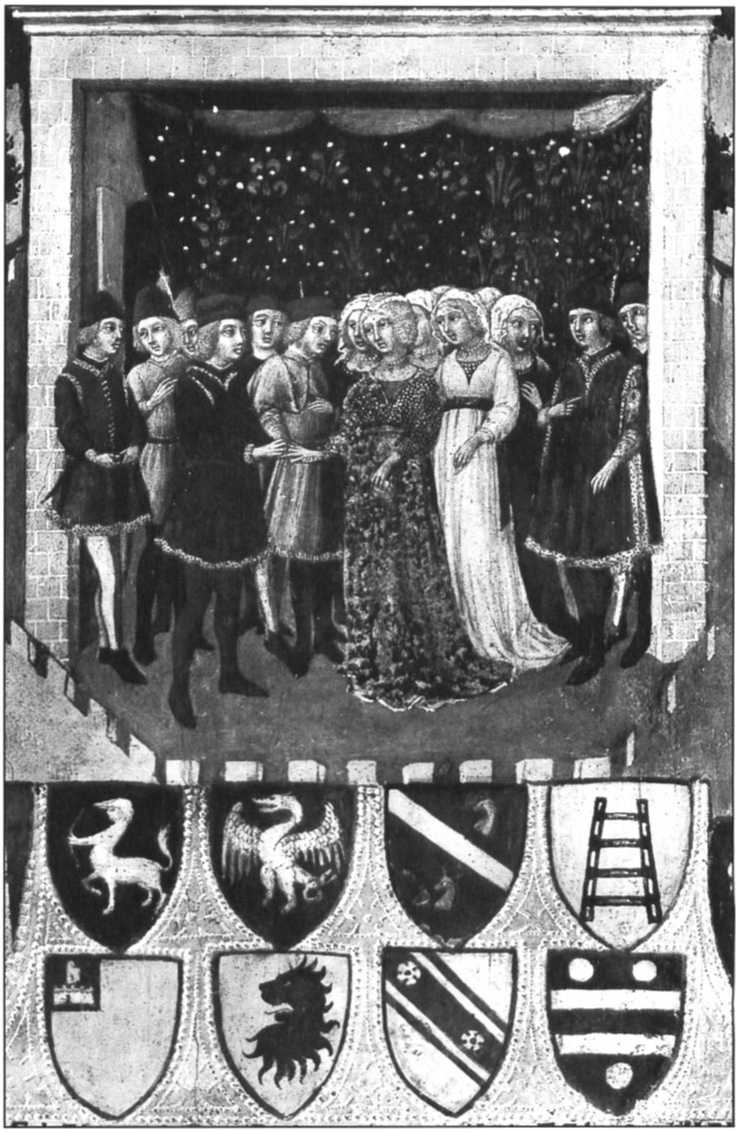

The refinements in court culture that courtly love brought to Europe included round dancing.

That winter. Finally, in the spring, an Italian fleet arrived with more supplies. According to the accounts of a person who was there, Bohemund suggested that whoever broke the siege and entered the city would be allowed to keep it. But the chronicler went on to say that Bohemund had already made contact with a Christian inside the city walls, who let him climb up at night and open the gates for the crusading army. The crusaders were victorious, but the victory was short-lived. The Turks soon recovered and sent a large force against Antioch. Now the crusaders were stuck between a castle in the city center stiU held by Turks, and the Turks outside the city walls. They were reduced to eating rats. In desperation, Bohemund suggested that they try to drive off the Turks encamped outside the city walls. The crusaders won this battle, and Bohemund claimed the city for himself in defiance of Alexius.

The other nobles accompanying Bohemund were so angry with him that the crusade nearly fell apart at that point. The leaders resolved their differences, however.

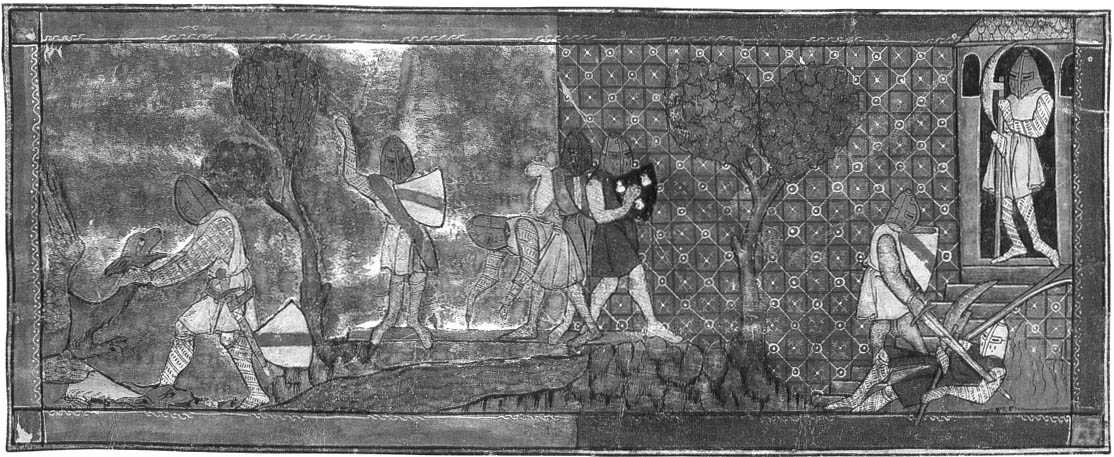

The assault on Antioch was long and brutal. The Turks held the city while the crusaders tried to attack it from the outside. The crusading army suffered from hunger and disease that decimated their ranks and led to fights among the leadership.

And continued on tojerusalem. The Italian cities sent fleets to supply food and siege equipment. In the summer of 1099, the crusaders took Jerusalem. It was a terrible defeat. One eyewitness said there was so much blood in the streets that it came up to the knees of the horses.

The leaders of the crusade discussed what to do with the territory. The petty fighting and land-hunger that had characterized the conquests seemed inappropriate in the holy city itself So they selected Godfrey of Lorraine, the only noble who had not participated in the internal dissensions, to be the first king of Jerusalem.

The Latin conquests in the Near East established the Latin Kingdom of Jemsa-lem, and several principalities were given as rewards to the nobles who fought. The whole experience of colonizing the region also had an enormous impact on Europe. Among the things that the crusaders returned home with were a better knowledge of building stone castles and machines to besiege them, a taste for more highly spiced foods, an appreciation of the luxury of silk and cotton garments, and a number of relics of saints from the early days of Christianity.

Life in Europe, particularly for the nobility and merchants, was becoming more refined even without the influence of the crusades. Contact with the Arab population of Spain had taught them to appreciate lyrical poetry as opposed to the heroic poetry of the chansons degeste and the sagas. Internal warfare decreased because younger sons went to Spain to fight Arabs or joined the crasades, and the resulting peace brought about a remarkable change in the nobles’

Anna Comnena, Byzantine Princess and Historian

Anna Comnena, born in 1081, was the firstborn daughter of Emperor Alexius and the oldest of his 11 children. Because of the long gap between her birth and that of her oldest brother, John, she harbored the idea that she would become empress. In her book, the Alexiad, she wrote that her real troubles with John began when she was eight. She was to be married to the rightful heir to the throne, who was then a boy of about her age. She assumed that together they would take over from her father, who had usurped the throne. But the marriage never took place, and she was eventually married to

Another man. Thereafter, she blamed her brother, John, for her failure to become empress. With a male heir, Alexius did not need her for the succession.

Anna received a fine education that included the study of literature, medicine, astronomy, and the mechanics of siege equipment. She wrote in the introduction of her book: “I, Anna, daughter of the Emperor Alexius and the Empress Irene, bom and bred in the Purple [born and raised as a princess], not without some acquaintance with literature—having devoted the most earnest study to the Greek language, in fact, and being

Not unpracticed in Rhetoric and having read thoroughly the treatises of Aristotle and the dialogues of Plato, and having fortified my mind with the Quadrivium of sciences (these things must be divulged, and it is not selLadvertisement to recall what Nature and my own zeal for knowledge have given me, not what God has apportioned to me from above and what has been contributed by opportunity).” She not only observed firsthand the events of her father’s reign, but also had access to men who had advised him and to other writings, including those of her husband who also wrote history.

Manners. The knights who went on the crusades had been warriors, trained to fight in battle. Those who remained in Europe, however, imbibed a new culture of military virtue called chivalry, from the French term for a mounted warrior, the chevalier. According to the code of chivalry, a knight was to be courageous (sometimes to the point of foolhardiness), loyal, trustworthy, generous to a conquered foe, and eager to defend the Christian faith. But chivalric behavior was to be practiced only by nobles and, for the most part, by males. The 12th-century refinements in living led to additional requirements for knights’ behavior: Noblewomen became objects of respect and elaborate courtesy; religious ceremonies surrounded the initiation of knights; and tournaments, or ritualized combat and warfare, became an entertainment.

Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, established a court in which the new noble values flourished. Her grandfather, Duke WilHam of Aquitaine, was a romantic figure known both for his love affairs and for the lyrical poetry he sang to his mistresses. Eleanor became the Duchess of Aquitaine upon her father’s death when she was a teenager. The adviser to the French king. Abbot Suger of the monastery of St. Denis outside of Paris, had arranged a marriage, with her father’s blessings, between Eleanor and the young king of France, Louis Vll (1137-1180).

The marriage was not a happy one because the two were so different. Eleanor had come from a sophisticated, worldly court in the south of France and dishked the damp chill of Paris. Louis had been raised to become a member of the clergy, perhaps even abbot of St. Denis, and was more clerical than knightly in temperament. He was forced to take the throne on the death of his elder brother.

The real difficulties between the couple occurred during the Second Crusade. Eleanor had given birth to two daughters but no sons, so she accompanied her husband on the crusade in the hopes of conceiving an heir to the French throne along the way. Dressed as female warriors, she and several other noble French ladies set off in high spirits. As if this behavior did not

THE FLOWERINS OF MEDIEVAL EUROPE • 83

Battling dragons (left) and fearsome knights (right), the legendary knight Lancelot fulfills his chivalric duties. In the Middle Ages, romances about the feats of the nobility were popular in the courts, and the most popular subjects of all were the stories that related to King Arthur, Queen Guinevere, Lancelot, and the other knights of the Round Table.

Cause enough scandal, when the couple arrived in Antioch Eleanor announced to Louis that she would remain there with her uncle, Raymond. Rumor abounded that she and Raymond, a handsome man and great warrior, were having an affair. She was said to have commented of Louis, “I thought to have married a king, but I married a monk.” After their return to France, she stiU had not produced a male heir, and Louis agreed to solicit the pope for an annulment of their marriage. The marriage was dissolved and she returned to being Duchess of Aquitaine.

But as an heiress, Eleanor remained a very desirable marriage partner. She was pursued by Henry, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy, who had met her in Paris when he had come to pay homage to Louis VII. He was only 18 and she was nearly 30, but marrying her would make him the Duke of Aquitaine. Furthermore, he was in line to become the king of England. They were wed barely eight weeks after the annulment of Eleanor’s first marriage. It is hard to imagine a bigger blow for Louis VII. Henry was his greatest rival, and now his rebellious vassal had combined his inheritance of

Normandy, Anj ou, and England with that of Eleanor. Together these counties and duchies were larger than the land that Louis personally controlled in his kingdom. As a further wound to Louis’s dignity, Eleanor produced four sons by Henry. A mighty feud arose between Henry and Louis.

Her marriage to Henry left Eleanor with responsibilities for maintaining his interests in the duchy of Aquitaine, but it also gave her a considerable amount of free time. Henry had political responsibilities in England, Normandy, and Anjou, so Eleanor was often alone in her own duchy. Her court was one of the most cosmopolitan in Europe. Her personal understanding of the world included the learned philosophy of Paris, the ways of Norman and English nobility, the exotic culture of the East, and the traditions of her grandfather, the poet. Poets and nobles were attracted to her brilliant court at Poitiers.

The combination of poets and young courtiers with the time to pursue refinement produced new standards of polite behavior around the court (courtoisie, or courtesy), a new emphasis on the importance of women as epitomized by courtly

Love, and new lyrical poetry and tales of romance that celebrated the changing relations between men and women of the noblility. Under the patronage of Eleanor and her daughter, Marie (daughter of Louis VII), rules of behavior in love were established. Men were instructed concerning in how to address ladies and were punished in a “court oflove” if they offended a woman. Poets known as troubadours composed lyrical poetry in celebration oftheir love for women and wrote tales called romances, in which the love of the hero and heroine were tested by a number of separations and adventures. Many of the romances retold legends from the past about King Arthur, Lancelot, Guinevere, and the knights of the Round Table. Troubadours traveled widely seeking patronage from various nobles, and in this way the poetry, tales, and rules of behavior of courtly love became fashionable all over Europe.

Troubadours could be either professional musicians or nobles. Bernard de Ventadour, for example, was the son of a servant in a castle. Viscount Ventadour was his patron, but Bernard was very attracted to the viscountess and addressed a number of his love poems to her. When her husband became jealous, Bernard sought the patronage of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Other poets included a noble man, Bertran de Bom, who wrote with tenderness about his love of war. He wrote of his enjoyment of the lusty spring with the songbirds singing and of the sight of the tented armies in the field. But what he liked most was to hear the cries of batde and the din of swords on armor and to see “ hones mad, with rolling eye, who frenzied through the batde fly.” The warrior, he wrote, thinks “but of blood and butchery and yearns for death or victory.”

Authors of romances included Marie de France, an educated woman living in England. She told the story of one of Arthur’s knights who had never known love. He was out hunting one day and shot an arrow at a white doe, but the arrow glanced back and strack him in the thigh. The doe told him that he would not be healed until he won the love of a lady. He then took to the sea, but his boat was shipwrecked on the shore of a beautiful garden. There a lady, who was imprisoned in a tower by her cmel husband, found him and nursed him back to health. But the husband discovered the knight and sent him off again. After a long separation, the husband was slain, the knight and his lady love were reunited, and they lived happily together. Having found love, the knight's leg healed.

The music for lyrical poetry differed from church music. The plainchant, in which all voices sang the same parts in unison without instmmental accompaniments, had been common in church services since the time of Gregory the Great. But the chansons degeste were sung to the accompaniment of a harp, and the troubadours played a stringed instrument with a bow— probably in imitation of Arabic musicians. Polyphonic compositions, which include parts for different voices such as tenor and bass, gradually became part of both religious and court functions.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, one of the most influential figures of the day, contributed hymns to the Virgin Mary to the music and poetry ofthe period. Bernard was raised with the traditional values of a nobleman.

Stringed instruments, perhaps adopted from the Arabs, accompanied lyric songs and played carols for round dances. The fiddle was an oval instrument with three strings that was played with a bow. The guitar was also a popular instrument in court

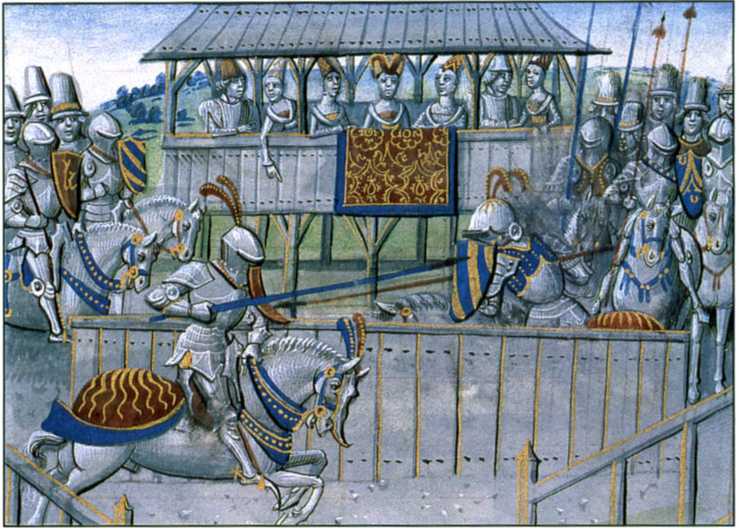

Tournaments, or mock battles, became both a way of keeping up fighting skills and of entertaining the nobility. They were an opportunity for rich display of fashions, feasting, horses, and armor as well as feats of fighting prowess. Ladies attended, cheering on theirfavorite knight. The fghting was highly ritualized, with lists (wooden barriers) to confine the fighting space. Heralds made sure that the rules of fighting were followed.

The worship of the Virgin Mary became very popular in the 12th century as hymns and churches were dedicated to Mary. Mary was shown as a gentle mother with the infant Jesus on her lap. People found it easier to direct prayers to this motherly figure than to the more distant God orJesus.

But had a conversion experience during an outing with some of his companions and joined a monastery at Citeaux, where he entered the new Cistercian order. Although they followed the Benedictine Rule, Cistercians tended to be stricter in their observance than the Cluniacs, and emphasized manual labor. By the time ofBemard’s death in 1153, the same year that Eleanor established her court in Aquitaine, the Cistercian order had spread throughout Europe. It was Bernard who had persuaded Louis VII to undertake the Second Crusade, and he had been an adviser to Louis and Eleanor. But he could not prevent their separation, and he grieved at the failure of the crusade.

Bernard was a great leader in theology as well as an inspiration for monks and mon-archs. Among his major accomplishments were the hymns to the Virgin Mary, which greatly increased her popularity in the Church at the time. More and more, churches were dedicated to Mary, and ordinary worshipers found that addressing prayers to Mary was more comforting than addressing them to Christ the lawgiver, as he was depicted in the apses of cathedrals. Mary became the subject of popular veneration and was often addressed in the same terms of adoration as the noble ladies were in love lyrics.

Noble men organized tournaments, or war games, that were suitable to the new court culture. Knights who did not go on crusades or engage in combat for long periods saw tournaments as an opportunity to exercise their skill with arms with minimal potential for loss oflife and limb. Tournaments were organized by nobles to celebrate the knighting of a son, the marriage of a daughter, the coronation of a king, the heroic entrance of a prince into a city, or as part of yearly urban celebrations. In fact, any excuse was a good one for these mock battles. If single combat was the order of the day, then lists were set up in such a way that the combatants could charge each other on horseback with lances. Ifa mock battle, or melee, was planned, then a field for two opposing sides was laid out. Elevated seating permitted spectators, including women, to view the fights. In elaborate contests, whole towns were turned into fighting quarters, and the streets were filled with sawdust or sand so that the horses would not slip on the cobblestones. The mock battles were fought from street to street.

Every noble had his own distinctive coat of arms and ref sieved it in a book of heralds. Heraldry terminology was an elaborate language of symbolism that included such terms as chevrons (peaked stripes), rampant lions (on their hind legs), feur-de-lis (lily flowers), and various bars drawn left to right or right to left.

The tournaments not only permitted the knights to display their fighting prowess, but also included a number of other rituals that emphasized courtly behavior. Observance of the rules of the game was crucial. First, weapons and horses were inspected. The participants then presented a coat of arms declaring the origin of the fighter to the assembled dignitaries and ladies. (Anonymous fighters could display false coats of arms. Sometimes kings used these, because no one would knowingly fight against his king in open combat for fear of being charged with treason.) A fighter might also wear some favor from his lady, such as a scarfor sleeve, and fight in her honor. Although the knight might have wanted to gain the love of a lady, he could win material rewards as well. Organizers offered winners a piece of armor, a horse, or the right to take the suit of armor and horse of the knights they defeated.

This remarkable period also saw a revival of learning in Europe. Boethius’s translations of parts of Plato and Aristotle received new attention in the schools that grew up around the cathedrals. Students flocked from all over Europe to listen to famous teachers lecture. Lectures were given in Latin, the common scholarly language, so that students from all reaches could understand them. By far the most famous teacher was Peter Abelard (1079—1142). He wrote an autobiography, Historia Calamitatum or The History of My Misfortunes, thus much is known about his life. He was bom into a knightly family in Brittany. He could have inherited his father’s lands, but instead became fascinated by theological and philosophical arguments, and traveled

Throughout France to listen to various teachers. Paris was the center for these debates, and Abelard soon developed a reputation as the most subtle of thinkers. He had a number of students who paid fees to hear him lecture. He became famous throughout Europe, but especially in Paris. His book Sic et Non {Yes and No) presented arguments for and against a whole range of difficult questions, such as whether faith can be supported by reason, whether good angels and saints who enjoy the sight of God know aU things, and whether God is a substance.

In relating the history of his misfortunes in his autobiography, Abelard told of his romance with Heloise. The uncle of this very bright and beautiful young woman was a high official at Notre Dame cathedral. Wanting to provide the best instruction for his niece, he engaged Abelard as her tutor. Abelard’s description of their lessons recounted how they moved from reading books to kissing each other. The affair became more serious, and she became pregnant. The couple was faced with a dilemma. If they married, he would not be able to pursue a career in the Church, because the clergy had to remain unmarried. Heloise, not wanting to ruin his career, refused to marry him. But when their son was born, they were secretly wed. Not knowing that they had married, her uncle was outraged when he learned of the birth, and arranged for a group of thugs to assault and castrate Abelard. Abelard retired to a monastery and urged Heloise to do the same.

Although Abelard continued to write and lecture, some people, such as Bernard of

Clairvaux, believed that his thinking was close to heretical. While living in the monastery, Abelard wrote his autobiography. It was circulated widely, and Heloise read a copy. She, like Abelard, had by now become the head of a religious community. Reading the account oftheir love reopened the old wounds. She wrote a letter to Abelard in which she sympathized with his misfortunes but reminded him that she too had suffered. She did not think oftheir love affair as a sin and recalled that he was a singer oflove songs in those days. Heloise wrote: “But in the whole period of my life I have ever feared to offend thee rather than God; I seek to please thee rather than Him. Thy command brought me, not the love of God, to the habit of religion.” She felt like a hypocrite for loving Abelard and becoming a nun only to please him. Abelard wrote back as a father confessor rather than as a former lover.

The remarkable flowering of the arts in Europe had lasting effects, even into our own time. Courtly love and chivalry became the basis for polite relations between men and women and in society in general. The crusades marked the first major expansion of Europe into Asia since the Roman period and brought Europeans into contact with new products and ideas. The spirit of expansion and conquest never left people’s imagination and led to the age of discovery in the 16th century. The revitalized Church and the intellectual developments of the 12th century came to further fruition in the 13th century as lay governments—of both towns and monarchies—also began to prosper as peace prevailed.

World History

World History