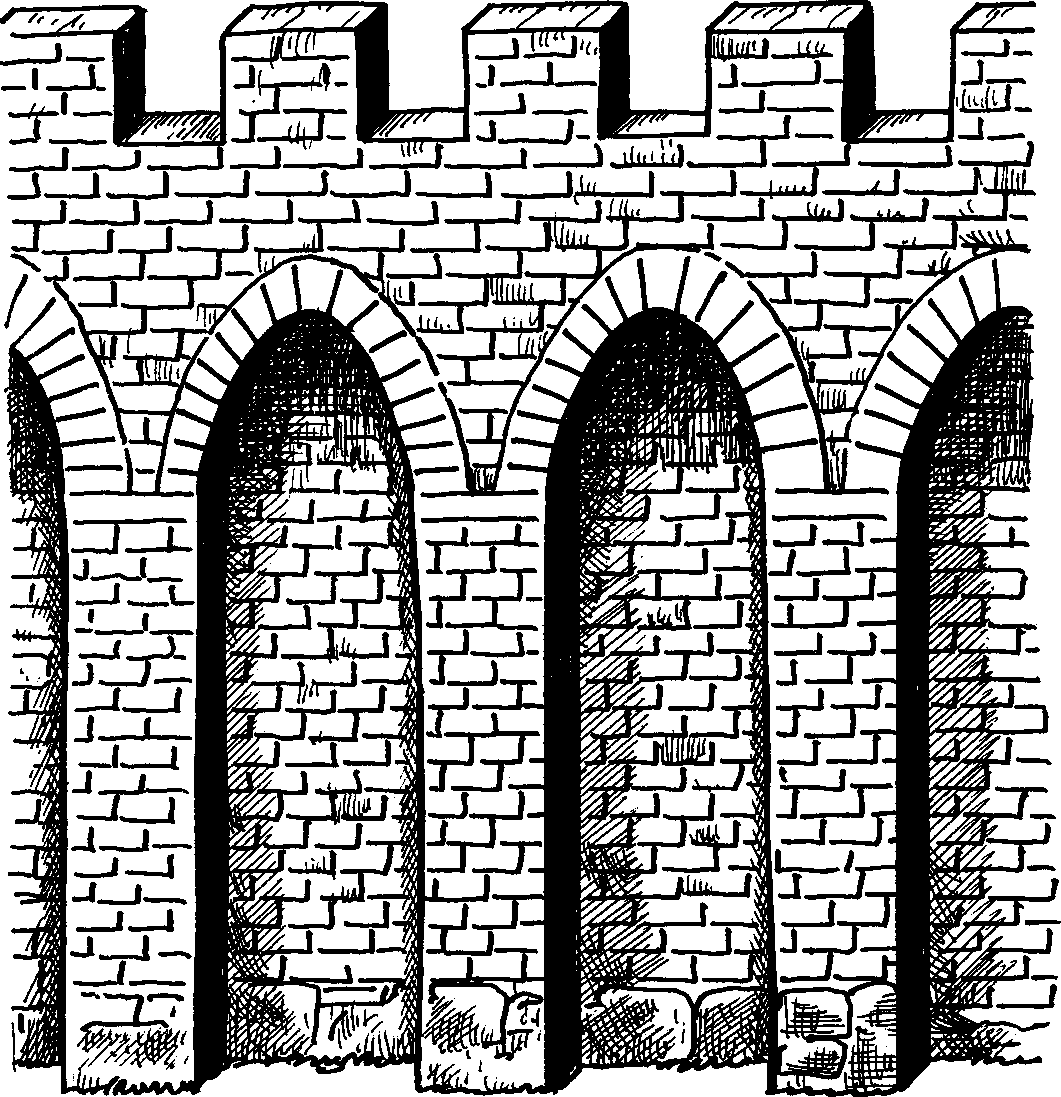

Beyond the drawbridge, the entrance to the castle was further defended by outer works. The barbican, originating in Arabian fortification, was placed on the far side of the moat in front of the gate. It concealed the entrance and protected it from enemy strike; it worked as a filter and formed an additional defense line. Usually a fortified outer ward, a low square stronghold or a masonry U-shaped tower, it was always fitted with crenellated parapet, its own ditch and its own gatehouse with drawbridge. As an exception, the barbican might be a round tower connected to the main enceinte by a double crenellated wall as can be seen in Carcassonne (southern France). The gatehouse to the barbican was usually placed not in line with the main portal but on a flank, so as to check a direct rush upon the latter. Possibly a barbican was fitted with sluices and water-gates allowing control of the water level in a wet moat.

Another outer-work was the so-called bastille. This was a large barbican which might have the dimensions of an independent castle with walls, towers, gatehouse, drawbridge and sometimes even its own garrison. It was usually built at the gate of a town. An example is the castle Saint-Antoine (the famous Bastille stormed in 1789), constructed over the period 1370-1382 (during the reign of Charles V) to defend the eastern access to Paris.

The Hundreds Years’ War was also marked by the drawing together of broad fortified fronts composed of castles, isolated watchtowers, strongholds, tower-houses, fortified farms, hamlets, villages and towns. Entrusted to loyal vassals, these fronts enabled both sides to conduct a wide strategy with supply-bases holding passages and controlling whole regions.

A significant innovation at the end of the 14th century was the creation of the so-called block-castle. This kind of stronghold was characterized by the absence of external walls, the abandonment of isolated combat emplacements, and the construction of a massive core in which towers were at the same level as the enceinte, creating a vast terrace on the summit of the fortress. This design facilitated communication from one part of the castle to another and allowed defenders to deploy their hurling machines (later firearms). Examples of this sort of disposition were to be seen in the Bastille in Paris and in castle Tarascon.

If 14th century castles were military strongholds, they were dwelling places, too. There was an increasing emphasis on the more domestic aspects of the accommodations. Castles had always been domestic to some degree, but domestic considerations came in a poor second to those of defense from the 11th to the 13th century. In the 14th and subsequent centuries, however, the demand

For more space and greater comfort was quite evident in the plan of new castles and the additions to existing ones. In the new structures the appearance was still very much that of a fortress, but internally they were houses. New foundations in the 14th and 15th centuries fully reflected the period’s attitudes with regard to domestic comfort in fortified premises. Such new castles were, however, greatly outnumbered by existing ones where, for simple economic reasons, it was not possible to build entirely afresh. In such cases the demand for greater domestic

World History

World History