In the hot, dry, and often rocky lands of the Mediterranean, gardens were both interludes of beauty and the status symbols of the wealthy few who could ignore agriculture's first claim on fertile soil.

Shown on a papyrus (left) dating from 1300 BC, an Egyptian scribe and his wife salute the god Osiris in a garden whose essential features—water and trees arranged in a regular fashion—provided a

Pattern for later developments such as those overleaf. Creek residential plots were rarely large enough to accommodate private gardens, but their public meeting places were adorned with fountains and shady trees. Interior gardens were a common feature of the town houses of wealthy Romans, who also practiced topiary and built conservatories in which to nurture foreign plants and grow roses out of season.

State decided who would survive, and unwanted female babies, as well as the weak and deformed, were exposed at birth or thrown over a cliff. Elsewhere, exposure might not mean death if the child was found and taken away, although it would probably end up as a slave. Children could also be intentionally given away or sold; a childless noble who craved an heir might supplement the income of a poor family by buying its unwanted children.

A Roman father signaled his acceptance of a newborn child simply by lifting it from the floor where the midwife had placed it after the birth. There would then follow a period of about ten days before the child was named, in case some new reason emerged for not accepting it. Then, provided its health was good, the Greek or Roman child could often look forward to a happy five or six years before its education began. In the case of Greece, large numbers of vase paintings and literary references testify to the undoubted affection in which children were held.

The education of Greek and Roman children was organized along similar lines, differing only in detail. In most of Greece, children were reared by the mother: The father's outdoor life kept him away from the house. The care of grandparents was considered to be valuable and was easy to manage since they frequently lived in the same house. At about the age of seven, boys were put into the charge of a tutor who either was hired for the purpose or was a responsible slave who was already a member of the household. He would supervise a boy's education until adolescence. How much teaching a boy received would depend on the wealth of the household. By the fifth century BC in Greece, especially in Athens, teachers who were specialists offered their services in such subjects as grammar and music; outside the home, in the agora, itinerant professional teachers made a living by teaching rhetoric and argument to those who could afford to pay. Youths also practiced military and athletic skills, such as wrestling.

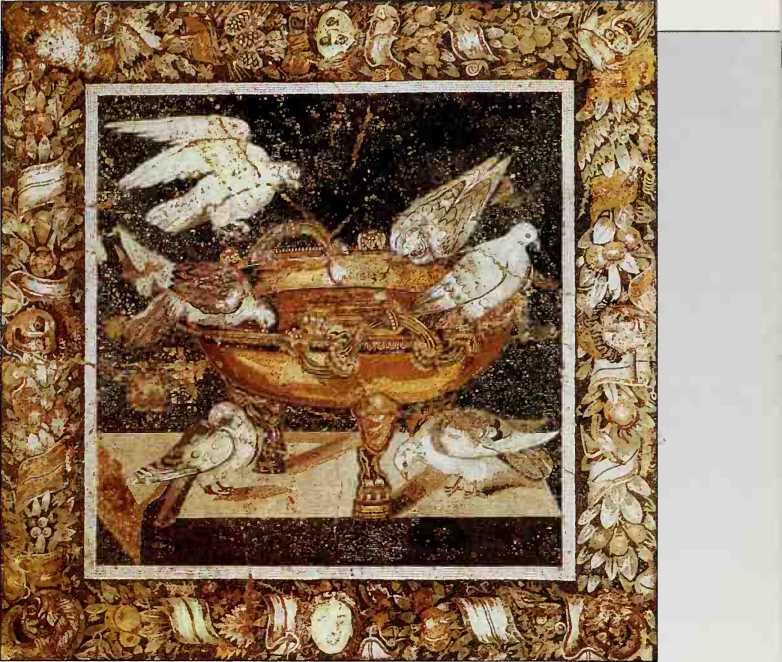

This first-century-BC painting of a garden wall, from an underground room in the villa of Livia, wife of the Roman emperor Augustus, was designed to give an impression of cool luxuriance during the heat of summer. At right, women on a painted Greek vase play ball, and birds sip from an ornate garden bowl on a Roman mosaic from Pompeii—scenes suggestive of the freedom from daily chores and the natural tranquillity that only gardens provided.

As in so many other areas of life in classical Greece, Sparta was an exception. The most important values of Spartan culture were discipline, courage, obedience, modesty; the intellectual aspects of life were not considered important. Boys lived at home with their families until they were seven years old and then left to enter a strict, communal military life until the age of thirty. Toward the end of his training, a Spartan youth spent a period of time living alone in the countryside, where he preyed on the unfortunate slaves who worked the land; he was required to kill at least one of them before being admitted to manhood. Then he resumed his barracks existence as part of Sparta's standing army.

Spartan girls and women were allowed to indulge in naked exercise in the gymnasium, an exclusively male pastime in most poleis. Elsewhere, however, Greek girls received no education other than in housekeeping skills, probably at the hands of a trusted slave. Secluded in the women's quarters, girl children were brought up to be good wives and mothers, and competent housekeepers—the only fit roles for females in the eyes of Greek society.

In Rome, where many teachers were Greek immigrants, part of the purpose of an expensive education was to set the elite apart from the common people. Teachers sought to inculcate a knowledge of both Greek-inspired culture and an appropriate superior manner—right down to the smallest physical gesture—to fit the wellborn for future power. The emphasis on this rigid notion of cultural attainment did not completely overshadow the still-'alued athletic and martial skills, but these were no longer designed to prepare every citizen for military service.

Wellborn Roman girls, like their mothers, enjoyed a little more freedom than was thought proper in Greece, but they too were reared with only one eventual aim in mind: a good marriage. These were usually arranged without consulting the parties: The closeted Athenian bride, for example, probably saw her future husband for the

First time only on her wedding day. Throughout, the woman was treated virtually as property; she would pass from the "ownership” of her father's family into that of her husband's kin and would become the responsibility of her husband. With her came a dowry of cash or possessions, an important and expensive consideration for a man with a daughter.

As a girl passed from one family to another, so she also passed from virginity to wifehood, a transition marked by various rituals in the wedding ceremony. After a day of feasting in the separate houses, the bride was symbolically seized from her old home and taken at night in a cart—its quality appropriate to her station—to the groom's house. Once across the threshold, the bride and groom moved to the hearth, the symbolic center of the home. There, in the Greek version of the ceremony, they were showered with nuts and small cakes for good luck. At last, the marriage could be consummated. The terrors that this might hold for a girl—often no more than twelve or thirteen years old, and away from her childhood home for the very first time—can only be imagined.

Rich or poor, a wife had little opportunity to vary her family's diet or experiment with new foods. Barley was the mainstay of ancient Greece, and because the grains had a coarse outer husk they had to be roasted and then pounded in a wooden mortar before being ground between the two stones of a quern, a simple hand mill. Barley meal found its way into cakes and a porridgelike gruel, but did not make good bread—"fodder fit only for slaves,” as one Greek commentator put it. The Romans preferred wheat, much of it imported from North Africa and other parts of the empire to satisfy the enormous demands of Rome and other major cities. So great was the importance of wheat in keeping the populace of Rome well-fed and contented that emperors organized free distribution of grain to Roman citizens. The emperor Tibe-

Rius warned the Roman Senate in the early decades of the first century AD that if the wheat dole were discontinued, "the utter ruin of the state will follow." At that time around 330,000 tons of grain were being shipped yearly to the port of Ostia at the mouth of the Tiber River, from where it was ferried about twenty miles upstream to Rome by a shuttle service of specially built flat-bottomed boats. Even so, there were constant grain shortages in Rome and other major cities.

Two kinds of wheat were in general use. The superior husk-free varieties that could be ground without prior processing, and that made good bread, were reserved for the rich. Poorer people still lived on a kind 6f porridge, usually eaten with vegetables, that was made from a primitive and inferior husked wheat that had all the drawbacks of barley. After the first century AD, flour and bread were increasingly produced by donkey-powered stone grinding mills and public bakeries, and the strenuous pounding of husked grains fell to gangs of prisoners shackled together.

The Greek and Roman diet was supplemented by vegetables and fruit, meat and fish. For the Greeks, the olive was as important as it had been as early as the third millennium BC for the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete. Valued because of its resistance to the droughts that killed off cereal crops and its ability to thrive in barren soil on hillsides where little else could grow, the olive tree's berries yielded oil that—as well as fuel for lamps and a basis for perfumes and cosmetics—provided a nutritious food that was far more dependable than grain. The Romans, in their turn, began to develop better varieties of fruits and nuts, including walnuts, sweet chestnuts, cherries, and apples. The elaborate network of paved Roman roads that crisscrossed most of the empire also made it possible for a much wider range of produce, including exotic spices from distant provinces, to find its way to Roman tables. Under favorable conditions, reasonably fresh fish could be enjoyed by Romans living fifty miles from the sea; most Greeks living away from the coast, however, had had to be content with dried or salted fish.

Throughout the classical period, meat was eaten in large amounts only on special occasions such as religious festivals, which usually involved the sacrifice of animals. The celebration of the founding day of a city, for example, held in honor of the town's patron god, would warrant at least one ox. All the gods needed was the smoke from the roasting fire; the officiating priests sometimes reserved a share of a sacrificed animal for their own private use, but most of the carcass was divided up among the crowd. Women and slaves attended public festivals even in Greece; for the latter, and for the poorest among the free citizens, these celebrations provided what was probably the only meat they tasted. When the festival was over, the priests would leave a small selection of poorer cuts of meat on the altar, ostensibly for the gods. Under cover of darkness these would be spirited away by beggars.

If grain was the staple food, the most important drink, after water, was wine. The milk of sheep and goats was quickly made into cheese, which gave it a longer life; beer was known to the Romans after their conquest of the beer-drinking Germanic tribes to the north, but wine remained the principal drink of all classes in both Greece and Rome. Beer had been a common drink in early civilizations such as Sumer in Mesopotamia, where it had been used to form part of the army's pay, and where a significant proportion of the grain production had been reserved for brewing into alcohol rather than making food. Vines had grown wild on the island of Crete, where the stimulating effects of the fermented juice of their grapes were discovered by the Minoans, for whom wine became one of their chief exports. The grapes were usually

On a fifth-century-BC gravestone from the island of P6ros, a girl cradles two tame pigeons. Although offerings of food were left on family graves at certain times of the year, the official religions of Greece and Rome prescribed no set beliefs concerning an afterlife. Many citizens commissioned private memorials such as the one shown here, portraying with affection the deceased enjoying the pleasures of everyday life.

World History

World History