Theories of 'representation' and 'consultation' appear in European writings from about 1000 together with the belief that consultation in government was natural and desirable. Early consultative assemblies were essentially enlarged royal councils, where matters touching the kingdom in general could be discussed. These were ill-defined bodies where membership was non-elective and 'representative' only in so far as the magnates who attended them were deemed to act on behalf of the wider populace. There was no suggestion that 'representation' derived from election, nor that it stemmed from any association with particular areas or social groups. In the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries the shifting burden of government, particularly of taxation, produced significant change in the range of consultation. Growing royal requirement for revenue to meet the costs of increasingly sophisticated government stimulated demands for wider consultation before the granting of taxation. Behind such developments lay recognition of the wealth and rising economic power of classes such as the townsmen and the royal desire to tap that wealth as a source of revenue.

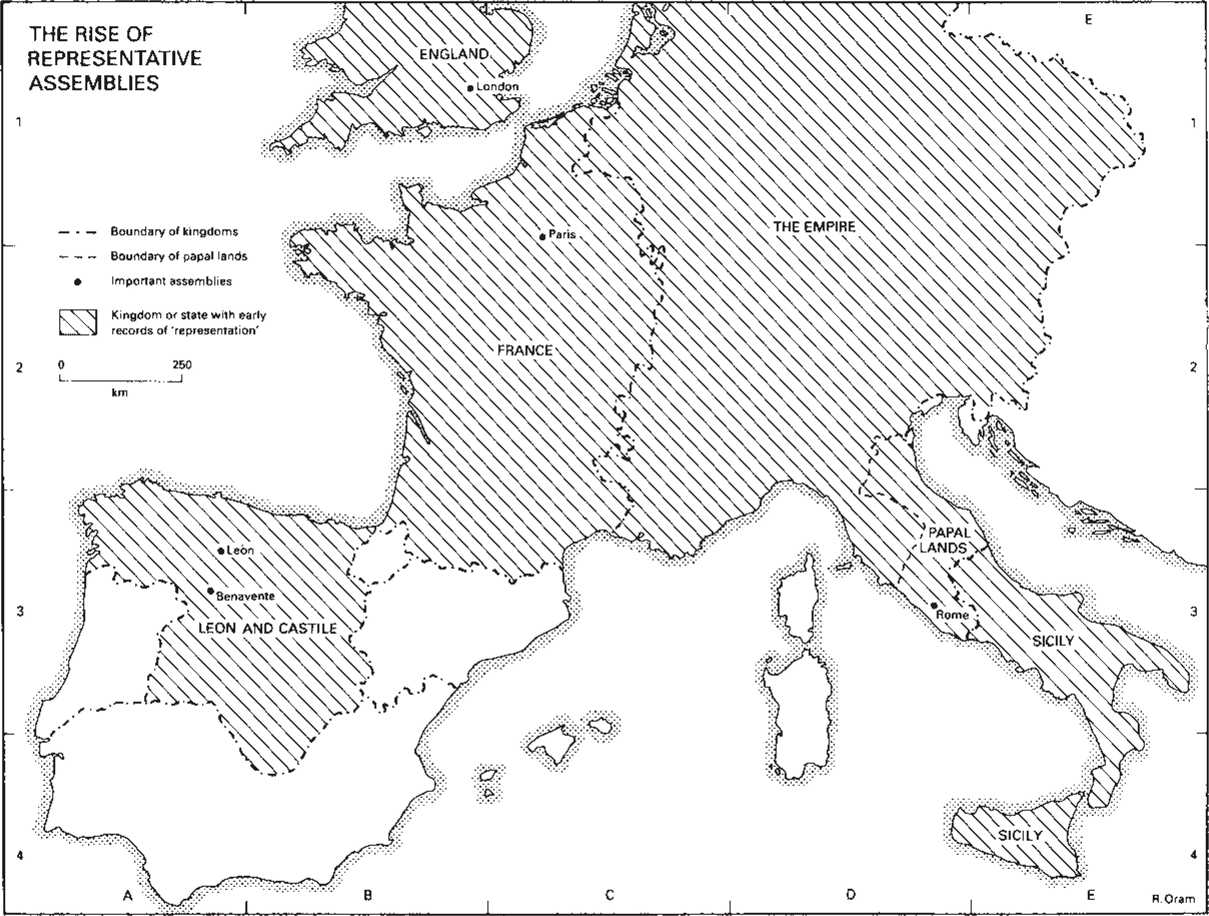

First evidence for a widening of representation in royal councils to include non-aristocratic or clerical members comes from Spain. There the process arose from Alfonso IX of Leon's search for broad popular support to strengthen his hold on his throne. To an extraordinary meeting of his curia at Leon in 1188 he summoned town representatives as well as the bishops and magnates, initiating the type of wide-based assemblies referred to as 'cortes’. This innovation recognized the power which the wealth of the towns commanded and which the king sought to harness to his own needs, fiscal and political.

In subsequent cortes, as at Benavente in 1202 or Leon in 1208, townsmen were summoned specifically to assent to a tax. Similar developments in Sicily under Frederick II were also tied to the levying of taxes, such as that granted in 1231 by a wide-based council, and the need to secure broad-based support to facilitate collection. Summonses to townsmen were again issued in 1232 and the practice had become so deep-rooted that in 1267 Pope Clement IV instructed Charles of Anjou to consult his subjects before raising a tax. The military and financial demands of the struggle with Frederick II on the papal lands led there to increased consultation over the issue of taxation, with negotiations in assemblies coming to be dominated by the townsmen. Within the empire proper, royal power was considerably more circumscribed after the upheavals of the reign of Frederick II, but in the later thirteenth century under Rudolf I, regnal assemblies composed of men from all areas and social ranks were used as a means of re-establishing royal power through collective endorsement of legislation on a national level.

Moves towards increased representation in England arose largely from conflict between crown and baronage in the early thirteenth century. At the root of the conflict were basic economic issues, taxation and lack of consultation, and in 1215 clauses of Magna Carta were devoted to resolving such matters. In England, however, although the principle of no taxation without the 'common counsel' of the realm was established, the scope of consultation was restricted at first to the nobility, and only from the late 1260s were the boroughs represented in parliament on a regular basis. Increased representation in France arose from

A different response to the same issue of taxation. There the king was for long able to levy taxes with the assent of his usual restricted circle of advisers, without any attempt to widen membership or make it more representative. Instead, there were moves towards negotiations between separate social groups and royal officials. In the thirteenth century towns negotiating payment of taxation sent representatives to regional meetings, while the nobility and the Church treated separately.

Despite the widening of the range of

Representation in royal assemblies throughout the thirteenth century there appears to have been no corresponding development of a theory of estates. Although society was seen as being composed of 'orders' there was no assumption that the orders needed separate representation. Moves towards divisions such as the three 'estates' of France, or the two 'houses' of parliament in England, although stemming from earlier circumstances, were largely developments of the fourteenth century.

R. Oram

World History

World History