In the 12th century, most Norman castles in Britain consisted of the motte-and-bailey castle made of earthwork and wood. They were also built in Denmark, Norway, the Low Countries, the Rhineland and South Italy, all regions which came under Viking influence, and it has therefore been suggested that the motte-and-bailey castle was perhaps a Norman invention, or if not, one which the Vikings took up and exported. At that time England was a densely forested land and large parts of the low-lying districts were covered with oak trees. Oak was the traditional building material.

There was, of course, no standard design, as each motte-and-bailey was built by a private owner. Dimensions could vary a lot, but basically a typical motte-and-bailey castle, as the name implies, comprised two main parts.

The Motte

First there was the motte, a site which at once was both elevated and difficult to access, as the Normans were no less willing than the Celts before them to take advantage of height provided by natural features. If there was a suitable hill in the area it could be adapted by scarping, steepening the sides by cutting away the lower slopes in order to make a flat-topped cone. If no escarpment was provided by nature, an artificial mount (10 to 15 m) was erected. Part of the material for the motte derived from the ditch that surrounded it, but additional earth was required to bring the mound up to any appreciable size. The motte was more than a simple dump of earth. In many cases it was composed of several alternating horizontal layers of material, including stone, peat, chalk rubble and rammed or beaten-down earth, and a final coating of clay in order to resist erosion. The top of the motte was flattened and surrounded by a palisade. In the middle of this enclosed platform there was a building, usually a squat rectangular or square timber tower (often called the domus) topped off with a pitched or sloping roof. The domus was sometimes on stilts to allow for free movement of the garrison, or it rested on heavy timber posts, forming a strong foundation anchored in the motte. The domus had two or three floors. The lower level was a storehouse for supply and provisions. The upper floor, whose door was accessible to the ground by means of a strong removable ladder or a light timber bridge, served as a permanent dwelling place for the lord of the castle. It could also be reserved mainly for use in time of siege as a place of withdrawal from which, when the bailey had been taken, the defense could be continued. Direct assault up the steep slopes under a hail of missiles would have been daunting to the attackers, but starvation was also a potent instrument of war and the tower on the motte could have been little less than a trap unless outside help was certain and speedy. Besides, it was vulnerable to fire. The motte was often surrounded by a deep ditch, which could be filled with water. The timber tower on the motte was reached from the lower bailey either by a bridge carried over the ditch or by steps climbing the mound. Of course all the actual work — chopping down trees, digging ditches and throwing up earth, for example — was done with very primitive tools by the Anglo-Saxon villeins and serfs who were right at the bottom of the feudal social system. It should be noted that the French term motte (mound) has been transferred and limited in English to the ditch and transcribed as moat.

The Bailey

Second there was the attached bailey, placed at the foot of the motte. The bailey, in fact the largest part of the castle, was a subordinate courtyard sheltering the wooden subsidiary buildings of the lord’s household: hall, chapel, stables, byre, granary, service buildings, and accommodation, huts and workshops for retainers, servants and craftsmen, as well as corrals for animals, training ground for the soldiers, and gardens and orchards. The number, size and arrangement of baileys were infinitely variable and as can be imagined no two sites were exactly the same. The simplest type of bailey was usually oval-, D - or U-shaped. A motte could also have two baileys (as in Windsor Castle). In Old Sarum in Wiltshire, the bailey was an ancient Iron Age Celtic hill fort, which had been reused. The motte could be built on one side of the bailey or in the middle of it. The bailey formed a sort of small village enclosed by a ditch, another earth wall and another palisade, which formed a complete circuit around the whole site. This outer embankment served as the first line of defense, and the bailey was used as a refuge by the peasants of the neighborhood and their cattle in case of attack.

The motte-and-bailey castle could withstand the type of attack that could be mounted in the 11th century, except for the danger of fire.

Function of the Motte-and-Bailey Castle

The motte-and-bailey castle was a fortified residence, a stronghold to deter or repulse aggression from external foes, and a base from which the lord could launch raids and attacks on his enemies. The motte-and-bailey castle was designed with defense firmly in mind. At first it was merely a castle of subjugation, but it soon became a small political, economical, juridical, administrative and tax and toll collecting center, the very image of collective security, but also the symbol of oppression and seat of power for the military command through all the surrounding villages. It was the visible form of feudal social relations. A castle could not function for long without its locality. The peasants of the vicinity were burdened with a multitude of tasks. For example they were required to work on buildings and earthworks, and to find wood for the fireplace.

The appearance of a motte-and-bailey castle must have been strikingly impressive and picturesque, particularly as all the woodwork was brightly painted and the tower undoubtedly decorated. As it was rather small, cheap and quickly built, the motte-and-bailey castle was within the means of most junior lords, but it could not withstand a long siege. It was too small to hold a large volume of supplies or to

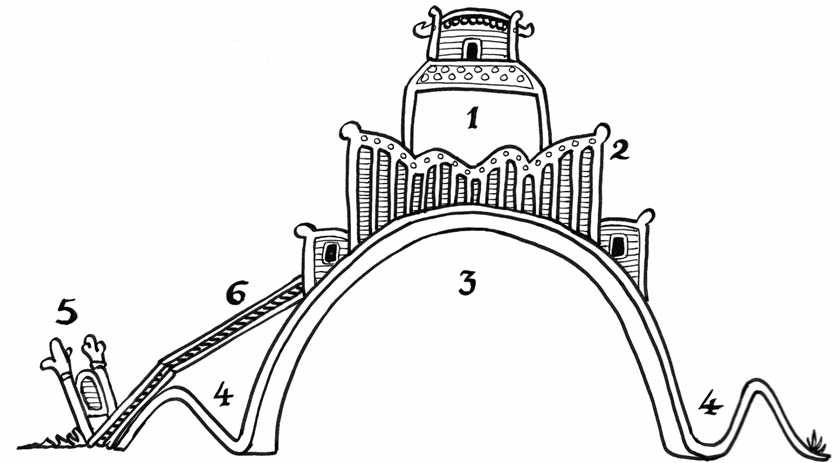

Top: If we are to trust the Bayeux Tapestry—whose accuracy is in other matters thoroughly borne out by all contemporary evidence—the motte-and-bailey castle of the Dinan, Normandy, France, included the following: the tower (1), and the palisade (2) on top of the motte or mount (3), the ditch (4), the gate (5) and the bridge (6) connecting the tower to the lower bailey.

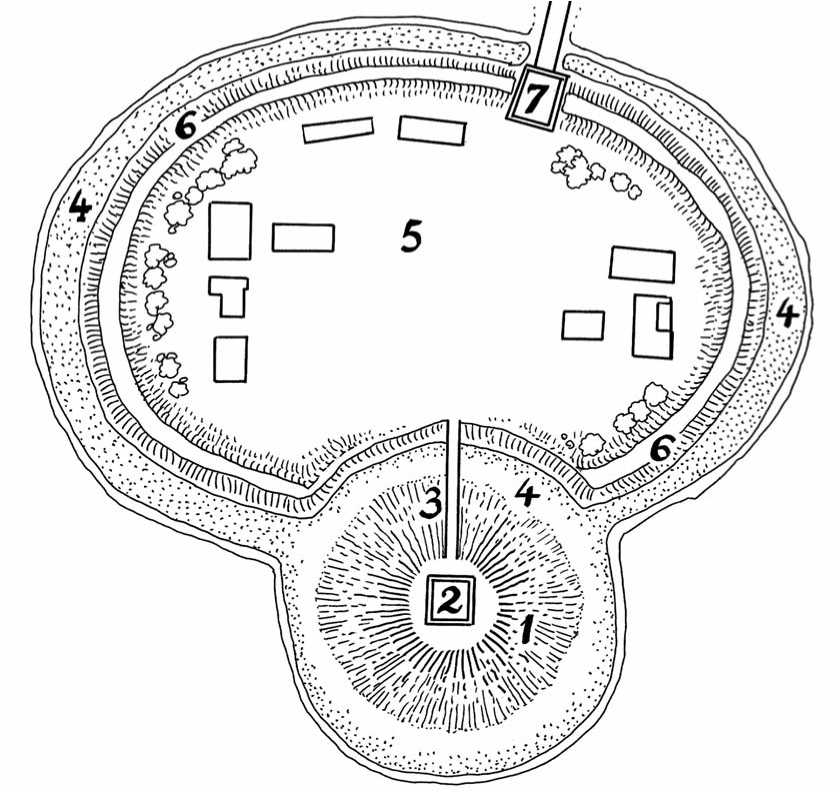

Bottom: The early medieval motte-and-bailey castle, in its simplest form (here based on Dinan motte-and-bailey castle as shown on the Bayeux Tapestry), consisted of a timber tower (1) on an earth mound or motte (2) with a palisade on top. The bailey (3) was a protected space featuring various service buildings. It was surrounded by a palisaded outer wall and a ditch (4).

Accommodate a significant garrison and the wooden defenses could be set on fire or chopped up relatively easily. Sadly, like the Alfredian Saxon burhs, none of these structures have survived. Timbered earthwork being highly vulnerable to the attrition of time, no motte-and-bailey castle has come down to us in complete preserved form, but we can see pictures of them on the Bayeux Tapestry.

In the landscape, only a few remnants of motte-and-bailey castles have been preserved in the parts of Britain into which the Normans penetrated. Several thousand were built during the century and a half following the conquest in 1066. In terms of distribution, motte-and-bailey castles are spread widely over England, Wales, Lowland and eastern Scotland, and the eastern half of Ireland — as a result of the invasion in 1167. A very large number of motte-and-bailey timber castles were built in

Laughton-en-le-Morthen is located to the south of Rotherham, South Yorkshire, England. 1: Motte; 2: Tower; 3: Bridge; 4: Ditch; 5: Bailey; 6: Earth wall with palisade; 7: Gatehouse and entrance.

The motte-and-bailey castle of Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire gives a good example of a Norman stronghold. The motte is 13.7 meters high and 55 meters in diameter while the bailey measures 137 meters by 91 meters.

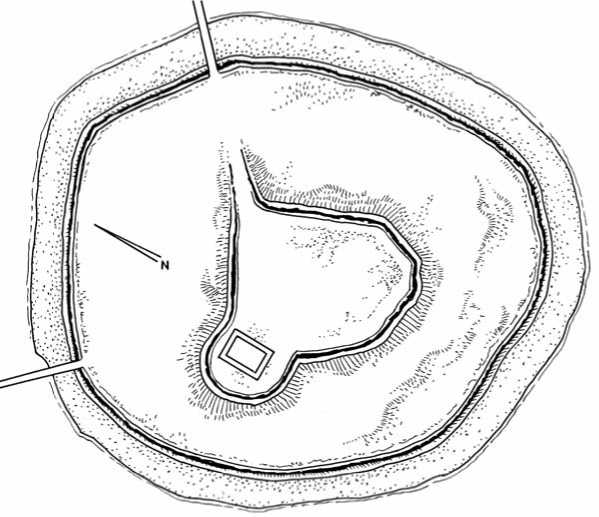

Duffus Castle, near Elgin, Moray, Scotland, was a motte-and-bailey castle built by a certain Freskin (probably a mercenary from Flemish origin) in c. 1140. The motte was a large man-made mound with steeply sloping sides hemmed by a wide and deep ditch. Over time the original earth and timber motte-and-bailey castle underwent many alterations, notably the replacement of palisades with stone walls, and the construction of stone buildings. The castle was occupied until 1705.

The early days of the conquest when the Norman lords established themselves in alien and hostile territory. There was another outburst of building during the civil wars known as the Anarchy during the reign of King Stephen (1135-1154) when many timber castles were constructed as temporary expedients, only to be abandoned and destroyed when order was re-established.

There is no point here to listing all British timber castles, but in England the more impressive sites are Rayleigh Mount in Essex, Pickering and Tickhill in Yorkshire, Berkhamstead in Hertfordshire, Thetford in Norfolk, and Tonbridge in Kent. In Scotland remnants of such fortifications may be seen at the Mote of Urr in Galloway, the Peel of Lumphanan and the Doune of Invertnochty in Aberdeen, and Duf-fus Castle in Moray.

World History

World History