The mismatch between administrative weaknesses and ideological aspirations in Charlemagne's empire gave rise to problems in the reign of his son Louis the Pious (814-40). Although his early rule was conscientious, personal and party conflicts provoked civil war between the king and his sons from 830. After Louis' death in 840 his eldest son, Lothar, whose power-base was Italy, sought to impose his power as emperor north of the Alps and deprive his half-brother Charles the Bald of his inheritance in west Francia. This encouraged Charles to make an alliance with his other halfbrother, Louis the German, and together they defeated Lothar at Fontenoy in 841. The alliance was consolidated by oaths taken by each king's followers at Strasbourg in 842. Lothar was compelled at Verdun in 843 to agree to a division of the empire into three approximately equal parts. Lothar kept his imperial title and lands stretching from the North Sea to Italy, which incorporated the imperial centres of Aachen, Pavia and Rome, while Charles obtained the west Frankish lands and Louis those east of the Rhine.

This arrangement was not envisaged as replacing the empire by nascent nation-states, but in practice centrifugal pressures were increased by rivalries between the rulers and the pressures of aristocratic supporters to regain offices and lands lost in the division.

Lothar's kingdom lacked viability and was divided in 855 among his three sons, none of whom had male heirs. As a result the kingdom of Lothar II (855-69) in the low countries was carved up between his uncles, Louis and Charles. In west Francia Charles fought manfully against Viking invaders and aristocratic separatism and succeeded in becoming emperor after the death of his nephew, Louis II, in 875. However, after his death (877) his descendants proved incompetent and short-lived. Louis the German proved the strongest king, but on his death (876) his kingdom was divided, and his sons died in rapid succession, apart from the youngest, Charles the Fat, who ruled a reunited empire fortuitously and ignominiously from 884 until his deposition in 887.

T. S.Brown

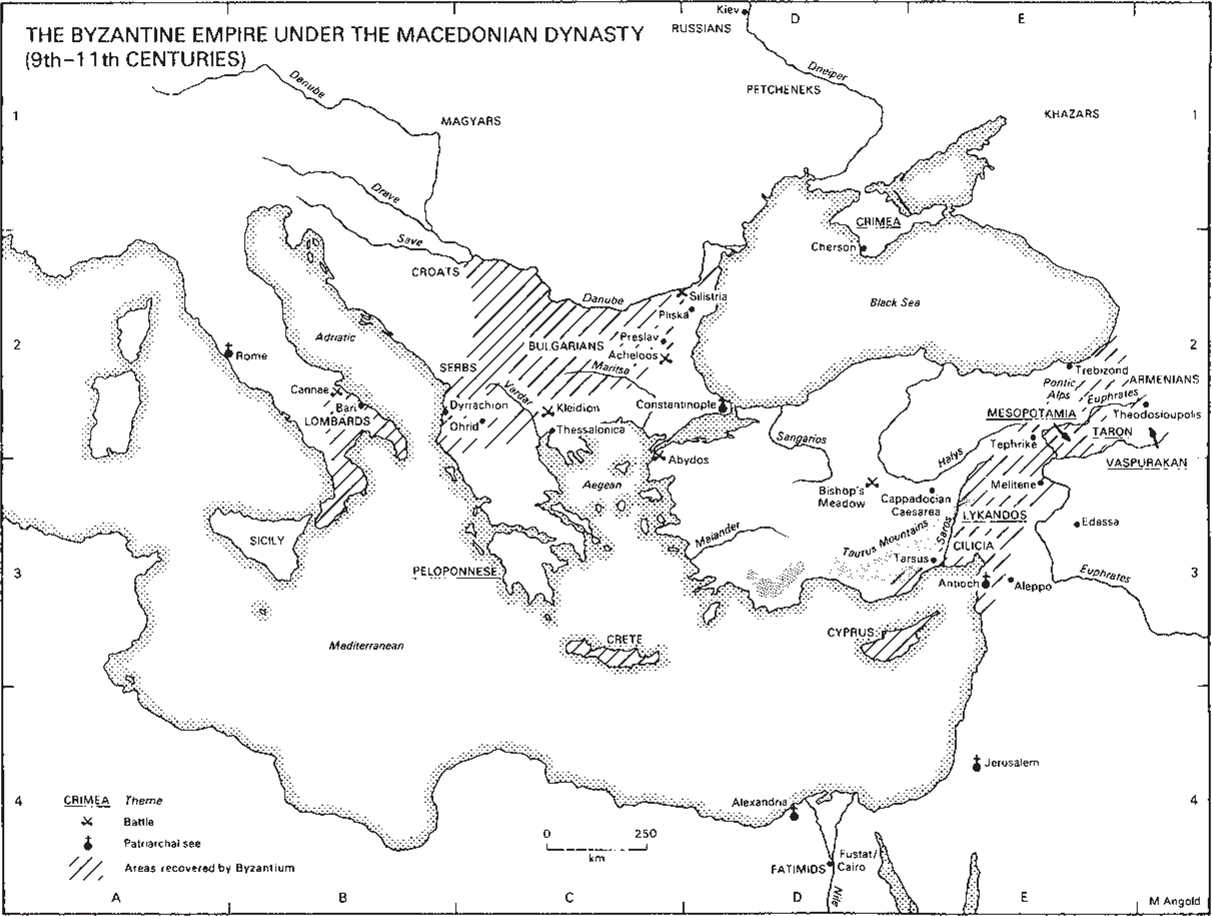

The Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian Dynasty (9th-11th Centuries)

From the mid-ninth century Byzantium took the offensive, responding to changes beyond its frontiers. After the battle of the Bishop's Meadow (863) the Arabs were never a real threat to Anatolia. Along the eastern frontier petty emirates emerged, not all of them in Muslim hands. Tephrike, for example, was held by the heretical Paulicians. Its capture in 878 brought the Byzantines within striking distance of the upper Euphrates. Care was taken to consolidate advances by creating new border themes, such as Mesopotamia and Lykandos (c. 900). Melitene, key to the middle Euphrates, fell in 934, and Theodosioupolis (Erzerum) in 949, allowing the

Byzantines to exercise more influence in Armenian lands, where a policy of piecemeal annexation was pursued. In 968 the Armenian principality of Taron was annexed and turned into a theme. These advances were complemented by the conquest of Tarsus and of Cilicia (965). Antioch fell in 969 and the city of Aleppo was put under tribute. The eastern frontier thus advanced from the Taurus mountains and the Pontic Alps to northern Syria and the lands of the middle and upper Euphrates.

In the Mediterranean the Byzantines were still on the defensive in the early tenth century, but the Arab corsairs of Crete were driven out in 960/

61 and Cyprus was taken in 965. Further successes in the eastern Mediterranean were checked by the arrival of the Fatimids in Egypt (969). They quickly extended into Palestine and Syria.

Conditions had also changed rapidly to the north of the Black Sea. Ever since the seventh century Byzantium had relied on alliance with the Khazars. From the early ninth century, however, a new people appeared in the shape of the Russians, who controlled the rivers leading from the Baltic Sea and the Caspian. Byzantium reacted by creating a theme in the Crimea centred on Cherson (833). This did not prevent a Russian attack nearly taking Constantinople by surprise (860). Other Russian attacks followed in 907 and 941, but Byzantium countered by offering the Russians valuable trading concessions.

The Russians also had to contend with the Petcheneks, the dominant power on the steppes. Byzantium cultivated them—they could cut the Russian trade route down the Dnieper from Kiev, and they also threatened the Bulgarians across the Danube. The conversion of the latter to Orthodoxy in 865 promised to bring them within the Byzantine orbit, but the Bulgarian tsar, Symeon (c. 893-927), was a more able opponent than his pagan forebears. He won notable victories over the Byzantines, including the battle of Acheloos (917), and in 921, 922 and 924 advanced to the walls of Constantinople. He mastered the Balkans and even penetrated the Peloponnese. He died in 927 and Byzantium hastened to make peace with his son Peter (92769). Over the next forty years the balance of power swung towards the Byzantines. In 967 the Russian prince of Kiev, Svjatoslav, was called in against the Bulgarians, but he determined to conquer Bulgaria himself. The Russians were finally defeated by the Byzantines at Silistria on the Danube (971) and Bulgaria was annexed. The returning Russians were caught by the Petcheneks and Svjatoslav was killed. It was a text-book demonstration of Byzantine diplomacy. Svjatoslav's death prepared the way for the conversion of his son Vladimir to Christianity.

Vladimir helped the Emperor Basil II (9761025) deal with a rebellion by the eastern themes, thus contributing to his victory at Abydos (989). These internal problems allowed the Bulgarians to establish a new state centred on Ohrid in Macedonia. Basil II concentrated on reducing the Bulgarians. Victory at Kleidion (1014) was decisive and by 1018 all resistance had collapsed. Basil II now extended Byzantine control in Armenia, annexing Vaspurakan (1021). He also strengthened Byzantium's hold in southern Italy, defeating the Lombards at Cannae (1018). It was an imposing achievement, but his successors found it hard to defend the new frontiers.

M. Angold

World History

World History