The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were the heyday of the religious image. Image-based devotional practices and image-inspired mystical visions penetrated all sectors of Christian society; specific images came to be associated with every important liturgical feast; pedestals, niches, tabernacles and brackets for the display of images were added to churches around the Continent; and mass-produced religious images assumed unprecedented propagandistic and commercial significance.553 Nonetheless, as Margaret Aston has noted, 'even in this image-filled period, attitudes toward images remained ambivalent'.554 Although clerics and the institutional church promoted and sought to profit from these trends (for example, by writing prayers to recite before images, by using prints to propagate pilgrimages and by issuing indulgences for veneration of specific sculptures and paintings), they also expressed discomfort with the emotional excesses such images often inspired, and could be suspicious of artistic innovation.555 The laity both embraced image devotion and, in the form of the Lollard movement, spearheaded resistance to it.556 By the late fourteenth century, complaints that there were too many images began to be more frequently voiced.557

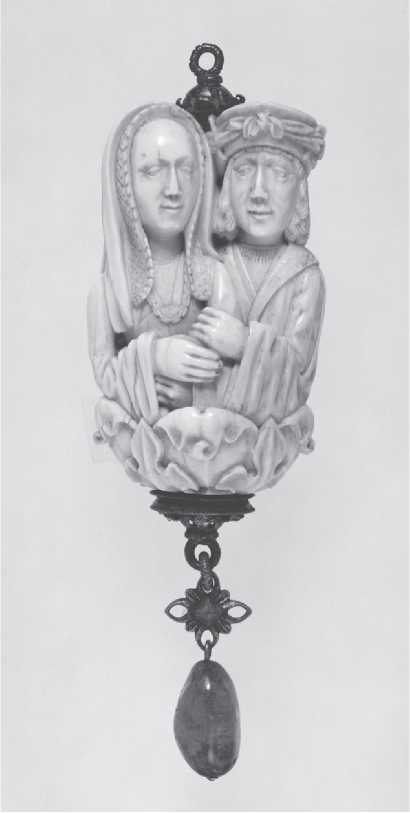

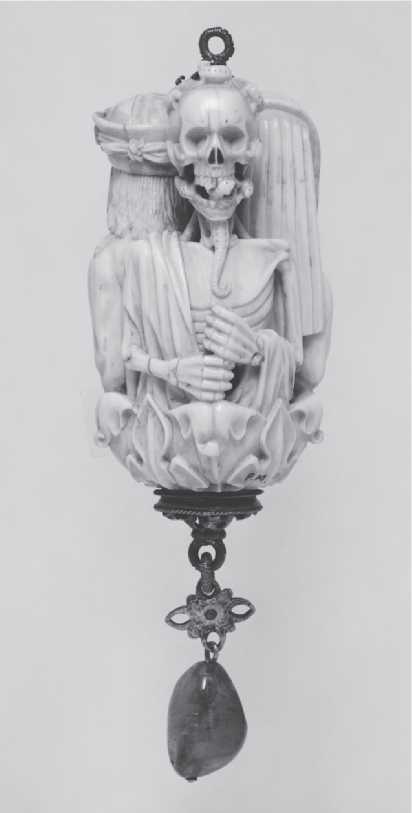

Like late medieval devotional literature, the devotional imagery of the period was characterised by intense pathos, often achieved through visual 'ugliness'.558 A late ffteenth-century 'Coffin of Christ' from Garamszentbenedik (Hungary) not only features elaborately carved and highly dramatic scenes of the Passion, but also became the resting place for a life-sized movable corpse of Christ during Easter processions. The Man of Sorrows (a half-length figure of the wounded Christ) became the most popular of all devotional images; in contrast to the Byzantine icons on which they were based, which connected the dead body of Christ to the Glory of God, western versions emphasised Christ's very human suffering. Vulnerability and pain likewise characterised late medieval crucifixes, and in pietas Christ's body became ever more gruesome, and Mary more deeply grief-stricken. The closely observed representation of physical and emotional suffering in such images may have helped their viewers to identify viscerally with their saintly subjects.559 Other images mirrored other forms of late medieval anxiety: themes such as the Three Living and Three Dead, the Dance of Death (first recorded in 1423) and decomposing skeletons served as vivid reminders of the perishability of the flesh (and, by implication, the immortality of the soul).560 Even luxurious decorative objects could have sombre undertones: a sixteenth-century ivory bead with entwined lovers on its front conceals a hideous skeleton on the back (see Figure 17.6).

The visualisation of anxiety and pain was designed to instill piety and penitence, but it also had its dark side in a concomitantly sharpened rendering of evil: late medieval art became a powerful vehicle for the conflation of religious fervour with social hatred. In representations of the Passion the tormenters of Christ became ever more hideous and cruel, and in illustrations of martyrdoms the number and ferocity of the

Fig. 17.6 Ivory rosary terminal bead with embracing lovers on the fTont and a hideous skeleton crawling with worms on the back. Germany, sixteenth century. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917, 17.190.305. (Photo: © Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Executioners increased.561 Many of these evil-doers were portrayed as extravagantly dressed ribalds, gross-featured peasants, turbaned Muslims or caricatured Jews - swarthy, hook-nosed and grimacing.562 In this period, too, libels accusing Jews of desecrating the Host and murdering Christian children began to be popular subjects for painting, prints and pamphlets.

Such images did more than merely reflect growing anti-Jewish sentiment - they almost certainly worked to intensify and channel it.563

By no means was all religious art of the period grim. Fifteenth-century Netherlandish and Italian painting combined complex symbolism with the latest developments in perspective and oil painting technique to create remarkably lifelike and brilliant holy tableaux. In Jan van Eyck's painting of the Madonna with Canon van der Paele in Bruges (1436), rich brocades, furs and silks, and the donor himself, share centre stage with an exquisitely lovely Madonna, an elegantly chivalrous Saint George and a luxuriously accoutred bishop-saint Donatian; the reality of the donor's mystical vision seems to be confirmed by the tangibility of the textiles. And many religious images doubled as luxurious household decorations, their holy subjects embodying the latest in elegance and style, while their vivid narratives simultaneously entertained and edified. The remarkable Unicorn Tapestries of c. 1500 at The Cloisters, for example, can be enjoyed as a spirited rendering of a late medieval hunt, as an allegory of Christ's Passion, and as a paean to courtship and fertility. So exquisite were many late medieval religious artworks that Jean Gerson felt compelled to instruct Christians not to worship an image just for its beauty.564

Image-based devotions had always had a strong tactile element, and in the later Middle Ages art more than ever facilitated the physical expression of religious feeling. Cribs containing sentimental images of the baby Jesus allowed nuns to treat the figure like their own child. While on pilgrimage, Margery Kempe would mark each important stop by reverently clothing an image of Christ; many people left money in their wills to pay for jewellery or clothing with which to adorn images of saints.565 The venerable devotional practice of embracing and kissing statues and crucifixes grew for some people into a daily habit.566 Genuflecting before a statue became an important demonstration of orthodoxy, and the failure to do so, cause for suspicion. Nor was physical interaction merely one-sided: increasingly images moved too. Late medieval northern altarpieces were furnished with moveable wings to be opened and closed during strategic moments of the liturgical year, and crucifixes and other sculpted figures were endowed with moveable limbs.567 By the end of the Middle Ages, one no longer had to be a gifted mystic to see religious art 'come to life'.

In the High Middle Ages religious pictures and objects served a dizzying array of purposes. They were used to glorify self, family, polity or institution, to exemplify virtue and/or embody vice, to bestow authority or authenticity, to protect a city or individual, to reinforce communal cohesiveness or corporate identity or to demonstrate their breakdown, to create a mood, to work miracles, to publicise a programme or pilgrimage, to raise funds, to spawn hatred, to stimulate the imagination or to trammel it. They could serve as gifts, containers, figureheads, signs or markers. Many of these functions remained common during the entire period in question; others waxed and waned according to social and religious needs and/or the prevalent artistic forms and media. But a few basic observations hold true across the Continent and throughout the centuries of the High Middle Ages. First, there is no simple categorisation of image use according to rank, gender or spiritual status: lay people, clerics and monks, men and women were all able to learn from and be moved by images. Second, the word-image opposition implicit in the cliche 'Book of the Simple' breaks down under scrutiny: images rarely if ever 'replaced' words, many images prominently featured words, images could be 'read' allegorically, just as words were, and by the end of the Middle Ages few if any liturgical or biblical words would have been totally free of visual associations. Third, artistic, theological and social change seem to have unfolded according to a delicate oscillating rhythm. High medieval images of Christ are often regarded as the most perfect visual expressions of the Catholic conception of a loving and compassionate God-Man. But Rupert of Deutz managed to see love and compassion in a crucifix well before such feelings came to dominate artistic renderings of Christ Crucified. Thirteenth-century devotional emphases on Jesus' scars and wounds anticipated more extreme later medieval images, which then in turn inspired further devotional excesses. And sometimes viewers encountered artistic change before they were fully ready to accept it. The history of Christian imagery suggests that ideas and images, doctrine, art and society existed in a complex relationship, with innovation appearing in sometimes one and sometimes the other realm. Finally and most basically, the manifold, overlapping and conflicting uses of images surveyed here confirm the centrality of the religious image in the lives of high medieval Christians. This centrality was acknowledged at the close of the Middle Ages in the ritual for visiting the infirm known as The Bake of the Crafte of Dying.83 Because moriens may be unable to hear, speak or understand, the Bake instructs, the priest should help him or her take solace in God's love by displaying an image of the crucifix. In the end, this text suggests, what is left to a soul deprived of all other means of access to the divine is sight. And art.

83 Carl Horstmann, ed., Yorkshire Writers: Richard Rolle ofHampole, an English Father of the Church, and his Followers, 2 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1895-96), vol. 2, 409-10.

World History

World History