The most obvious characteristic of Roman Britain was the development of towns, which were the basis of Roman administration and civilization. Many grew out of previous Celtic Britton settlements, but also from Roman military camps or market centers. Basically there were three different sorts of towns in Britain: a few coloniae— towns peopled by a majority of Roman settlers and discharged veterans; the municip-iae—a number of cities in which the whole native population was given Roman citizenship; and a majority of civitates (singular civitas), which included the old Celtic tribal communities, their towns, villages and settlements, through which the Romans

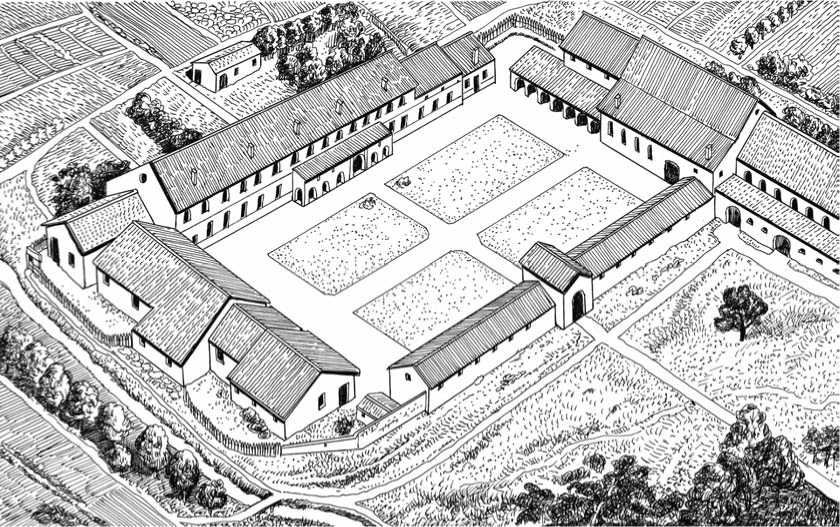

Roman villa. The illustration (based on Chedworth, England) shows how a villa might have looked around a. d. 350. A villa was a self-contained agricultural community, the focal point in many rural areas of the Roman Empire. A villa could have included hundreds of people living there, surrounded by hundreds and even thousands of hectares of fields. Located in or near the villa were orchards, herb gardens, flower gardens and vineyards. Animals kept here included horses, sheep, goats and pigs. The villa was often built around a central yard with buildings made of stones or bricks covered with a tile roof. Buildings included many different farm structures and workshops, such as a blacksmith, bake ovens, stables and so on. The owner and his family could either live at the villa in a residence or in a nearby town, in which case he had his estate managed by a foreman or overseer who conducted the work of gardeners, maids, nannies and other household servants, most of them being slaves. Some peasants would live at the villa, but most would live in small huts with their families in the fields surrounding the villa. Some would be slaves, others would be free farmers renting land from the land owner. A number of villas survived the collapse of the Roman Empire and grew into permanent settlements that eventually came to be called villages.

Administrated the native population in the countryside. Many coloniae and municip-iae were at first army camps and the Latin word for fortified camp, castrum, has remained part of many town names, indicated by the suffixes - chester, - caster or - cester; for example Gloucester, Doncaster, Winchester and many others. Soldiers and officials did their best to reconstruct the backgrounds of sunny Italy in this misty and wet climate. The newly created towns were built with stone as well as wood, and their streets intersected at right angles, forming regular blocks occupied by dwellings, markets and shops, a forum, baths, temples and a basilica. Towns were connected

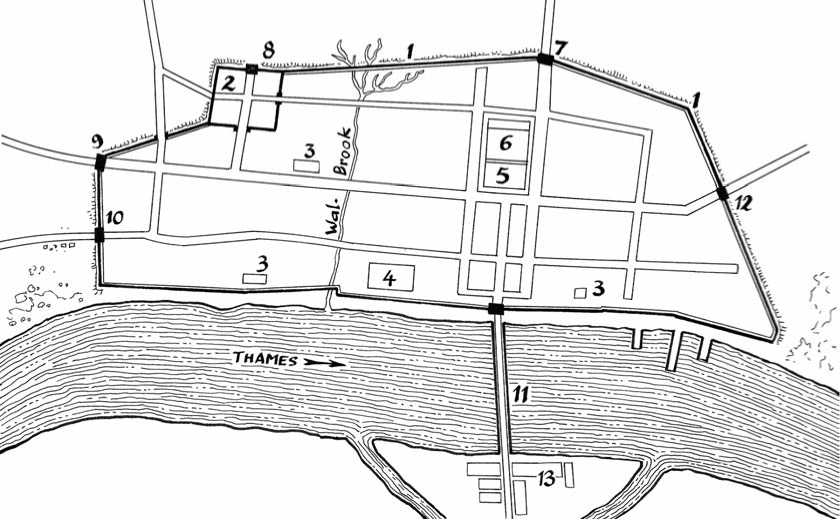

Roman London. Londinium was founded by the Romans in a. d. 50, at the point where the Thames was narrow enough to build a bridge, but deep enough to take seagoing vessels. Some ten years after its foundation, the town was sacked by the Iceni, led by their queen Boudica. Londinium was rebuilt, expanded rapidly, and soon became Britannia’s largest city, and an important commercial and trading center. By the end of the 1st century, Londinium had replaced Colchester as the capital of Roman Britannia. In the early 2nd century a large part of the city was destroyed by fire. London appears to have recovered, however, and by about a. d. 140 Londinium had reached a population estimated at 50,000. By the middle of the century Londinium included the following fortifications and major public buildings.

1: The wall, built about a. d. 200, enclosed an area of about 330 acres (130 hectares), was 6 to 9 feet (2 to 3 m) wide and about 18 feet (5 m) high, with a ditch (or fossa) measuring some 6 feet (2 m) deep by between 9 and 15 feet (3 to 5 m) wide. It included a number of walltowers (at least 20) spaced about 70 yards (64 m) apart; 2: Arx (built in c. a. d. 120, a citadel for the city garrison); 3: Public bath; 4: Praetorium (administrative palace); 5: Forum; 6: Basilica; 7: Bishops-gate; 8: Cripplegate; 9: Newgate; 10: Ludgate; 11: London bridge; 12: Aldgate; 13: Southwark suburb. In the second half of the second century Londinium appears to have shrunk in both size and population; the cause was possibly a plague epidemic and economic recession. The Romans abandoned London in a. d. 410.

By a road network, and six of them met in Londinium (London). Here the Romans chose a place on the north bank of the Thames where ships could lie in safety, and they built a walled trading city, which became later the capital city of about 20,000. The former capital of Britannia was, however, Camulodunum (Colchester).

Outside the towns, the most significant change during the Roman era was the growth of large agricultural demesnes named villas. These self-contained productive units included the master’s house, laborers’ dwellings, farm buildings, livestock, fields, meadows, orchards and vineyards. Villas belonged to some discharged Roman veterans, and to the local wealthy Briton chieftains, who, like most city dwellers, were more Roman than Celt in their manners and way of life. Admittedly the accommodations of the villas’ masters were lightly fortified. Some had a vallum (wall) and a fossa (ditch) of military appearance. Not that Britannia was particularly lawless, but it is easy to imagine that a retired Roman legate or centurion could not escape the need to continue his civilian life according to his army background, and that wherever he lived, there had to be a ditch and a wall around his dwelling, and his villa would not be an exception to that rule. The villas were generally close to towns so that their products could be sold easily.

At first Roman towns had no defensive walls, but that changed after the revolt led by the queen of the Iceni tribe, Boadicea (or Boudica) in a. d. 61 in what later became East Anglia. The Britons at first had great successes. They captured the hated Roman settlement of Camulodunum (Colchester). The warrior queen Boudica and

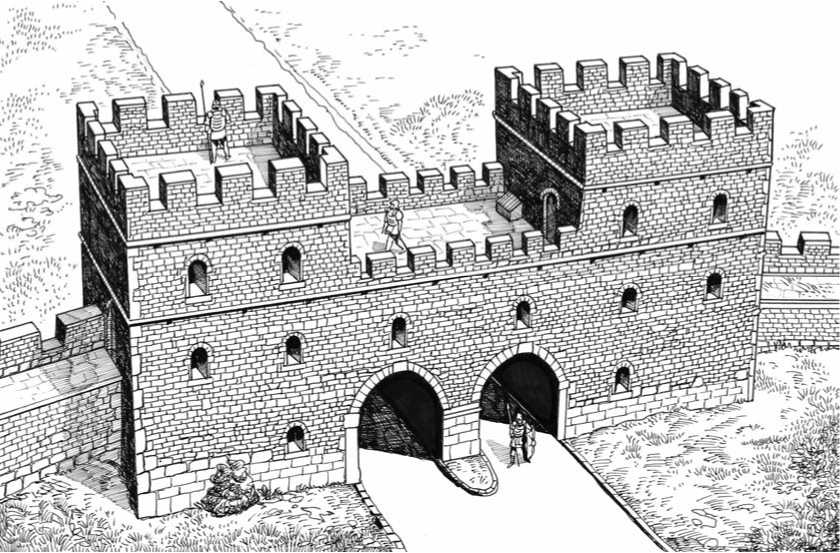

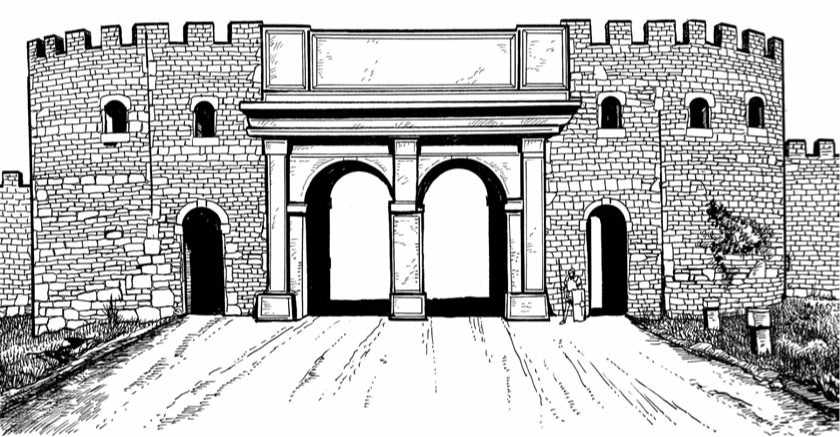

Aldgate, London, c. a. d. 200. The reconstructed gate shown here is seen from within the town.

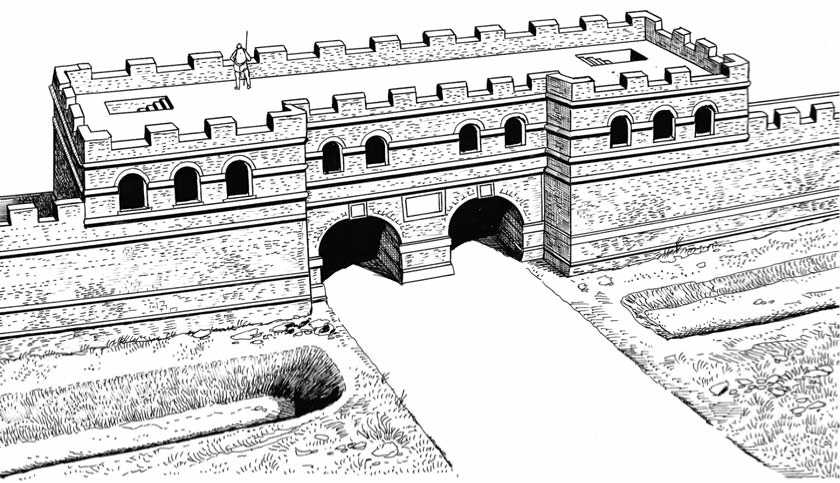

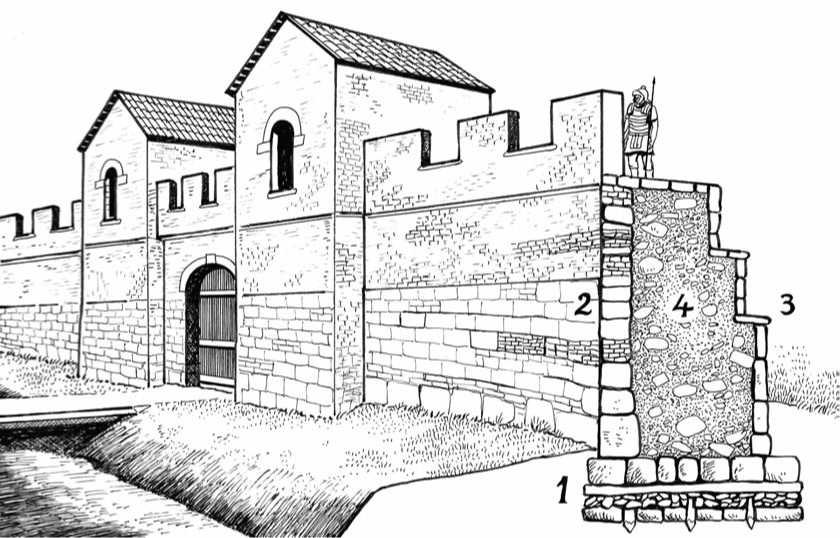

Gatehouse Chester (reconstruction).

Her allies gave no quarter in their victories and when Londinium and Verulamium (St. Albans) were stormed, the defenders fled and the towns were sacked and burned. Finally the Romans assembled an army of 10,000 regulars and auxiliaries, the backbone of which was made up from the XIVth Legion. The Roman historian Tacitus in his Annals of Rome gives a very vivid account of the final battle, which was fought in A. D. 61 in the Midlands of England, possibly at a place called Mancetter near Nuneaton. The rebellion was crushed, but important damage had been done to a number of towns deprived of defenses. Soon most veterans’ coloniae — the most reliable towns—became semi-militarized fortified centers. Then, from the end of the 2nd century to the end of the 3rd century A. D., almost every town in Britain, as well as many villas in the countryside, were fitted with fortifications, suggesting a policy decision taken at the imperial level. At first many of these were no more than palisades and earthworks, but by A. d. 300 many towns had stone walls with towers and gatehouses. Colchester, for example, was hemmed with a wall 3 km in perimeter (of which over 900 m can still be seen today), fronted by a 6-meter-deep and 3-meterwide ditch. The wall, fitted with walltowers, was made of rubble and mortar with inner and outer revetments of bricks alternating with layers of squared stone. The wall was about 3.7 m high, and featured a 1.8 m crenelated parapet. The city had seven gates.

As long as the Pax Romana (Roman Peace) reigned, urban fortifications apparently had, however, more a symbolic function than a real military significance. The gate generally had more the appearance of a triumphal arch than that of a fortified point, a fact particularly noticeable at the Balkerne Gate in Colchester. As for the

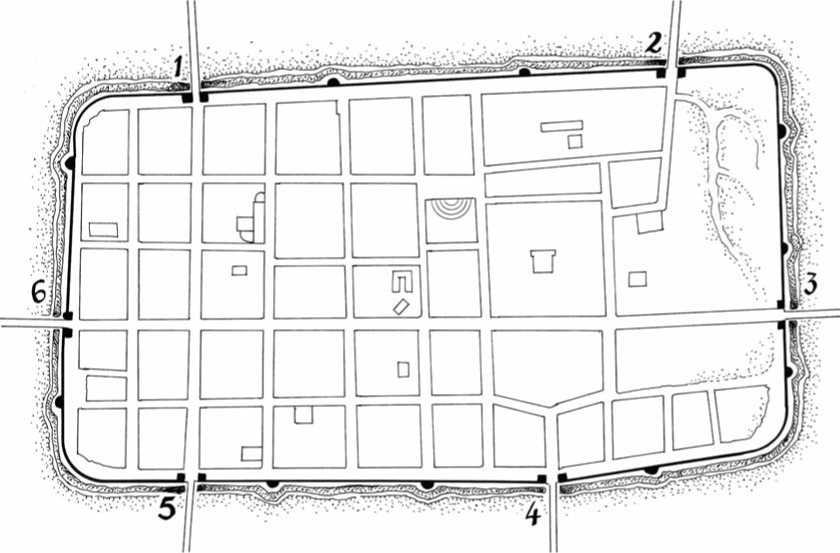

Roman Colchester. Colchester in Essex was one of the most important Iron Age settlements in Britain. It was the capital of the major pre-Roman power, King Cunobelin of the Catuvellauni and the Trinovante tribes. After the Roman invasion, it was established as a colonia named Camulodunum for retired Roman military officers and soldiers, and the city retained this high status throughout the four centuries of Roman rule. The map shows the town in the 2nd to 4th centuries. 1: North Gate; 2: Duncan’s Gate; 3: East Gate; 4: South Gate; 5: Head Gate; 6: Balk-erne Gate.

Towers, they were often constructed against the rear of the wall, which means that they did not protrude in the ditch, and therefore could not provide flanking fire along the outer curtain. Besides some important and large buildings such as arenas, theaters and amphitheaters were often built outside the defended perimeter.

In A. D. 367 the Picts, Scots and Saxons joined forces in a well coordinated revolt, which seems to have taken the Roman authorities by surprise. The fortified towns seem to have formed islands of refuge in an otherwise turbulent and unsafe countryside. This suggests that the reorganization of urban defenses had been carried out by that time. Already in a. d. 343 there had been trouble on the northern frontier, and forts and towns had been sacked beyond Hadrian’s Wall. There was evidence of destruction as far south as Great Casterton in Leicestershire in the Midlands, and the Emperor Flavius Julius Constans I (reign 337-350) visited Britain in person. The realization that raiders and possibly invaders from the north of Hadrian’s Wall could penetrate so far south may have impelled Constans to order a complete reorganization of urban defenses along more military lines. This was in keeping with the general pattern on the continent and reflected the growing defensive attitude of the 3rd

Top: The Balkerne Gate (Colchester) is one of the most impressive surviving gateways to a Roman town in Britain. It was built in the 1st century a. d., around a. d. 55. It began as a dual archway over the road to London. Ten years later, when the town walls were built, the gateway was adapted into these new defenses. In the 4th century a. d., most of the gateway was blocked with rubble, leaving only an arched footway open for pedestrian traffic. This was done to strengthen the defenses of the town when it was threatened by Saxon raiders.

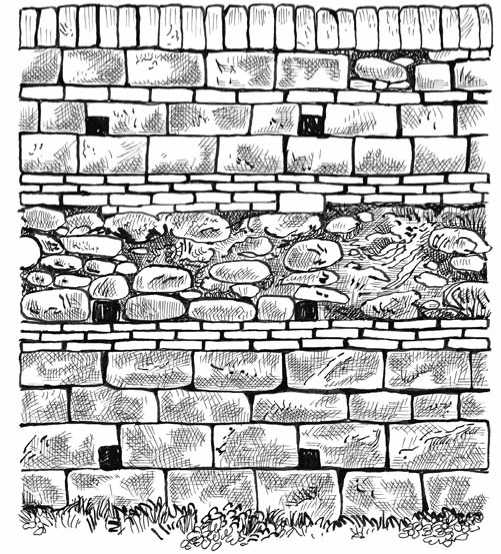

Bottom: Close-up of a Roman masonry wall. Towards the end of the 3rd century, offense was no longer possible, and this change in mentality was clearly reflected in stronger fortification designs, and heavy stone walls which represented a departure from simple earthworks of the preceding centuries. The close-up shows courses of large stone blocks forming the plinth, above which was the exposed rubble core of chalk, flint and sep-taria (beetle stone). Between them, brick bonding courses provided horizontal stability by running from the facing into the center of the core. Square holes were spared to hold the scaffolding.

Cross-section of a Roman wall. The foundations (1) consisted of large blocks, flint cobbles, and vertical wooden piles. The external revetment (2) was made of stone and brick bonding courses. The offset stone internal revetment (3) was larger at the base than at the top for increased stability. The core of the wall (4) was made of rubble and mortar.

And 4 th centuries in the western Roman Empire as a whole. In the first two centuries confidence and aggression were the hallmarks of Roman policy along its huge borders. In the 3rd and 4th centuries, however, due to the ever-increasing pressure of the barbarian tribes beyond the frontiers, and due to the enormous burden of maintaining large military forces, the forts, fortresses, and fortified towns were no longer springboards for attack and conquest, but purely defensive strongholds which might survive in a sea of aggression.

During their occupation of Britain the Romans founded a number of important settlements, many of which still survive. The main cities and towns which have Roman origins, or were extensively developed by them, include the following: Alcester (Alu-ana); Bath (Aquae Sulis); Caerleon (Isca Augusta); Caernarfon (Segontium); Caerwent (Venta Silurum); Canterbury (Durovernum Cantiacorum); Carlisle (Luguvalium); Carmarthen (Moridunum); Colchester (Camulodunum); Corbridge (Coria); Chichester (Noviomagus Regnorum); Chester (Deva Victrix); Cirencester (Corinium); Dover (Portus Dubris); Dorchester (Durnovaria); Exeter (Isca Dum-noniorum); Gloucester (Glevum); Leicester (Ratae Corieltauvorum); London (Londinium); Lincoln (Lindum Colonia); Manchester (Mamucium); Newcastle-upon-Tyne (Pons Aelius); Northwich (Condate); St Albans (Verulamium); Towcester (Lactodorum); Whitchurch (Mediolanum); Winchester (Venta Belgarum); and York (Eboracum).

Feet

N

4oo

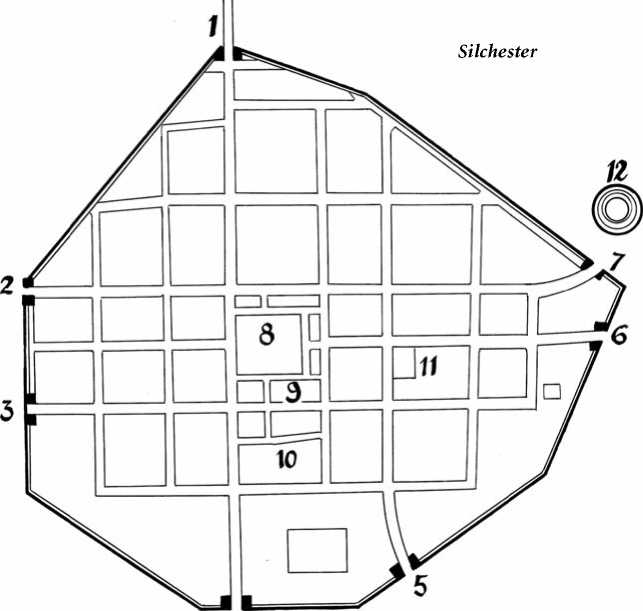

Opposite top: Silchester, located southwest of Reading in Hampshire, is best known for the adjacent archaeological site and Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum, which was first occupied by the Romans in about a. d. 45 and includes what is thought to be the best-preserved Roman wall in Great Britain.

1: North gate; 2:West gate; 3: West postern; 4: South gate; 5: Water gate; 6: East gate; 7: Postern to amphitheater; 8: Forum; 9: Church; 10: Temple; 11: Bathhouse; 12: Amphitheater.

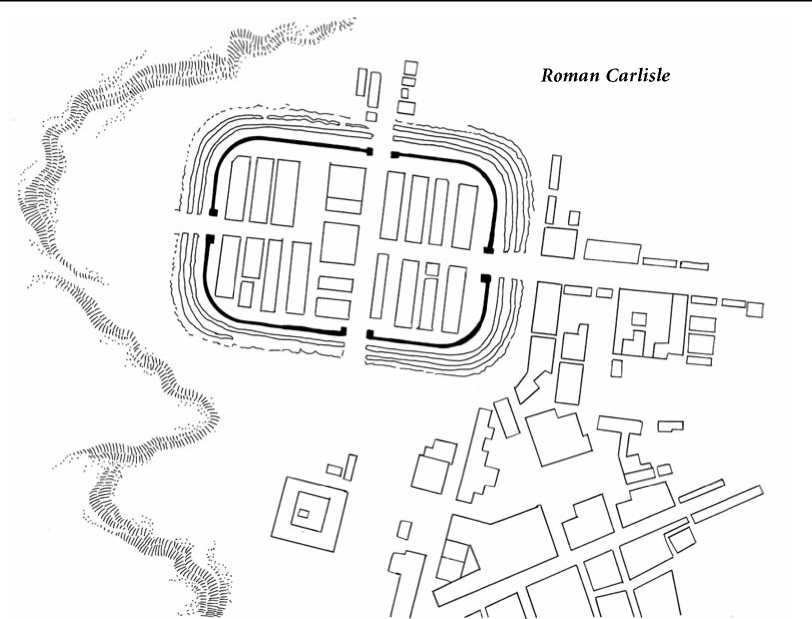

Opposite bottom: Roman Carlisle. After the Roman invasion in a. d. 43, governor Agricola built a wooden fort on the site of Carlisle in Cumbria about a. d. 78. Called Luguvalium, the fort attracted civilians and soon a settlement grew up nearby with a market and probably a forum with public buildings around it, including baths. By the 4th century Roman civilization had declined, troops were withdrawn from Hadrian’s Wall in a. d. 399 and the last Roman soldiers left Britain in about 407. Soon afterwards the Roman way of life broke down and most Roman towns were abandoned. Carlisle may not have been deserted completely. There may have been some peasants living inside the walls and farming the land outside. However, it seems certain that Carlisle ceased to be a town and all its Roman buildings fell into ruins. Carlisle was part of a Celtic kingdom until the 7th century, when it fell to the Saxons. The Celts gave Carlisle its name. They called it Caer Luel, the fortified place belonging to Luel. In 876 the Vikings captured Carlisle and sacked it. They occupied the town until the 10th century, when the Saxons once again captured it. Carlisle was rebuilt and revived by King William Rufus in 1092. He built a wooden castle, which was rebuilt in stone in the 12th century.

World History

World History