Members of all the social classes, with the exception of slaves, could take part in some aspect of government. The king was technically the head of a local government and was expected to do what was right for the people, including making sure that justice was served. According to The King's Mirror:

His chief business [is] to maintain an intelligent government and to seek good solutions for all the difficult problems and demands which come before him. And you shall know of a truth that it is just as much the king's duty to observe daily the rules of the sacred law and to preserve justice in holy judgments as it is the bishop's duty to preserve the order of the sacred mass.50

It would have been difficult for a Norse king to become a ruthless dictator, because many of his important decisions had to be approved by an assembly of freemen. Such an assembly was called a thing. Essentially a big meeting, it was held in the open air once, twice, or several times a year, depending on local custom. There were small-scale, town-level things, which dealt with land rights, local construction projects, and disputes among neighbors. Larger, regional-level things handled more important matters, such as choosing a king if the old one had died or deciding the region's defensive policies. Of all the Viking lands, only Iceland had a national-level assembly (the Althing).

One of the several functions of a thing was to deal with legal matters. First, at some point during the meeting an elected official known as the Lawspeaker read aloud a portion of the local laws. (In Iceland it was a third of the laws.) Then, a person could come forward and accuse someone else of wrongdoing. There were no lawyers, police, or other formal legal personnel, so the accuser prosecuted the case himself, and the accused ran his own defense. The accuser called witnesses to back up his charge. And the accused could and often did call a number of character witnesses to testify that he was of good character and therefore likely innocent. In a minority of cases, the accused endured an ordeal. For example, he might carry a hot iron from one point to another, and if he suffered no burns he was proclaimed innocent.

If the members of the thing found the accused guilty, punishment was meted out. The Vikings had no prisons like those in modern societies. Instead, convicted criminals most often paid a fine. This system not only satisfied the accuser, since he received tangible compensation for his losses, it also reduced the level of violence in Norse society. Any disputes that could not be settled in this civilized manner could result in the accuser and accused fighting a duel

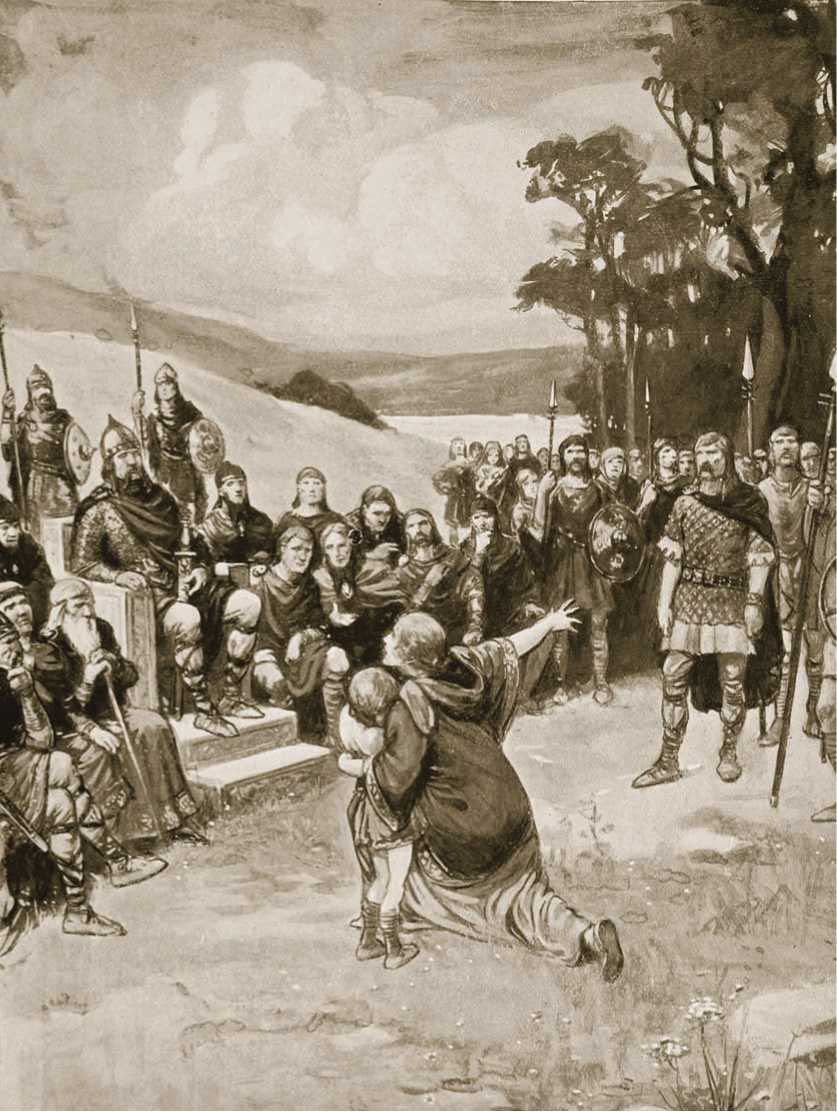

A woman accuses a man of wrong-doing in a local thing. Dealing with legal disputes was only one of several communal junctions of a Viking thing.

To the death. Another common custom (one the justice system sought to avoid), consisted of the accuser's family exacting blood vengeance by killing one or more members of the accused person's family.

If the local society viewed a crime as particularly heinous, the guilty person might be branded an outlaw. Murder, for instance, might result in outlawry (although sometimes the thing instead imposed a heavy fine for murder). It was forbidden for anyone to give aid or shelter to an outlaw, even a member of his own family; also, it was perfectly acceptable for anyone to kill an outlaw on sight. In some Viking lands, including Iceland, outlawry was the ultimate punishment. In others, including parts of Denmark, a guilty person could receive the death penalty. Common forms of execution included hanging, burning, stoning, drowning, and burying alive.

World History

World History