Coins were an essential element of Roman state administration and always played a key role in the process of extraction of resources, maintaining the government and its apparatus, and maintaining and supplying the armies. Coins provide information about prices and values, and they are also political objects, bearing symbolic imagery and inscriptions which reflect political values, official ideology and the propaganda and claims of a state or ruler. They cast light on methods and technologies of production, imperial fiscal policy, and on the relationship between centre and provinces, and between taxation and economic life in general.

The fiscal and economic crisis which beset the Roman empire during the third century was resolved in respect of monetary policy by the reforms of Diocletian and Constantine I. The older gold and silver coinages, along with the minor bronze and copper coinages of account, had become unmanageable. In the 280s, Diocletian inaugurated an important reform. A new gold coin, the aureus, worth 1/60 of a Roman pound, was introduced,

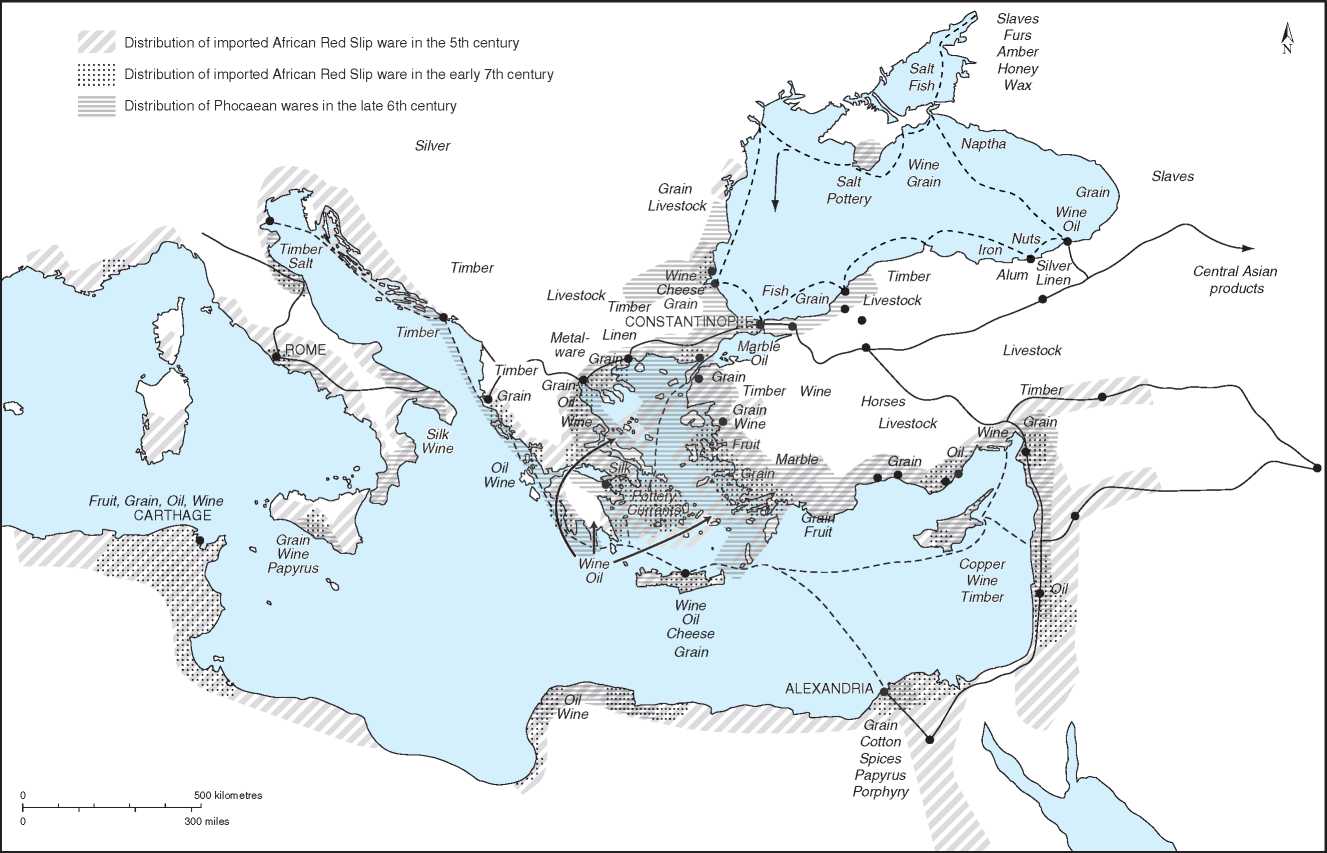

Map 3.5 Movement of goods as evidenced by ceramics.

Map 3.6 Mints, c. 527-628/9 (After Hendy, Studies).

Accompanied by a silver coin, of which there were 96 to the pound, and by a reformed billon coinage, the nummus (copper with a small silver content). Between 312 and 324 Constantine I transformed this system: the value of the gold coin was changed to 1/72 of a pound, and a second silver coinage, slightly higher in value than the Diocletianic coin, was introduced. During the fourth and fifth centuries, while the billon and silver coinages suffered a series of reforms and fluctuations in value and weight, the gold remained relatively stable. But by the reign of Anastasius the silver coinage was little more than vestigial, and the billon suffered from such a degree of instability that it became too cumbersome and inflexible to be employed in normal exchange. Anastasius (491-518), while modifying only slightly the gold:silver ratio and maintaining the stability of the gold, introduced a radically reformed copper coinage to replace the older base-metal coinage, with weights and values clearly marked, facilitating exchange across the whole system. While it did suffer from considerable fluctuations, especially during the seventh and eighth centuries, the reformed coinage remained the basis for copper coin until the later eleventh century. The reforms of Anastasius mark a convenient historical point from which the establishment of a specifically east Roman imperial coinage can be said to have taken place.

Silver, especially in the form of the miliarensis (Hellenised as miliaresion), a heavy coin struck at the rate of 72 to the pound, played a relatively minor role during the later fifth and sixth centuries, except in the empire’s western regions (especially those reconquered from the Vandals and Ostrogoths) until the reign of Heraclius, when the hexagram was introduced, a silver coin worth 1/12 of a gold solidus.

The administration of coin production and circulation was complex. From the fourth century into the early seventh century mints were under the authority of the comes sacrarum largitionum, the count of the sacred largesses, one of the leading financial officers of the empire, who also had responsibility for mines and bullion. There were a large number of mints across the empire producing gold and bronze coins until the early seventh century. Between 296 and 450 some 17 permanent and temporary mints stretching from London to Alexandria struck imperial coinage. The location of the mints reflected primarily political and military concerns - provincial mints in particular were mostly located in regions that had substantial military needs, such as garrisons and frontiers. After the disappearance of the western half of the empire, seven mints continued to operate, although that at Heraclea in Thrace was shut down due to barbarian pressure in the 490s. Gold was struck at Constantinople and Thessalonica, and with Justinian’s reconquests it was also struck at Carthage and Ravenna. Altogether there were at the end of the sixth century some ten permanent and two temporary mints. During the protracted Persian wars, from 603 to 626, minting in the enemy-occupied provinces and in other regions affected by the fighting stopped or was severely disrupted, and a number of temporary mints were set up with the specific aim of coining money with which to pay the army. As a result of some of these developments, the Emperor Heraclius undertook a major reform of the mints, probably in 628-629, a reflection both of a straitened state budget and ongoing changes within the state fiscal administration, in particular the gradual absorption into the various levels of the praetorian prefecture, on the one hand, and of the imperial vestiarion, the household administration, on the other, of many of the key activities and functions of the sacrae largitiones. The result was the closure of a number of mints and the concentration of the striking of gold at Constantinople, Carthage and Ravenna, the rest being permitted to strike copper only. While this structure changed slightly later in the seventh century (see below), it sets the pattern for the highly centralised medieval Byzantine production of imperial coinage in the Balkans and Asia Minor.

World History

World History