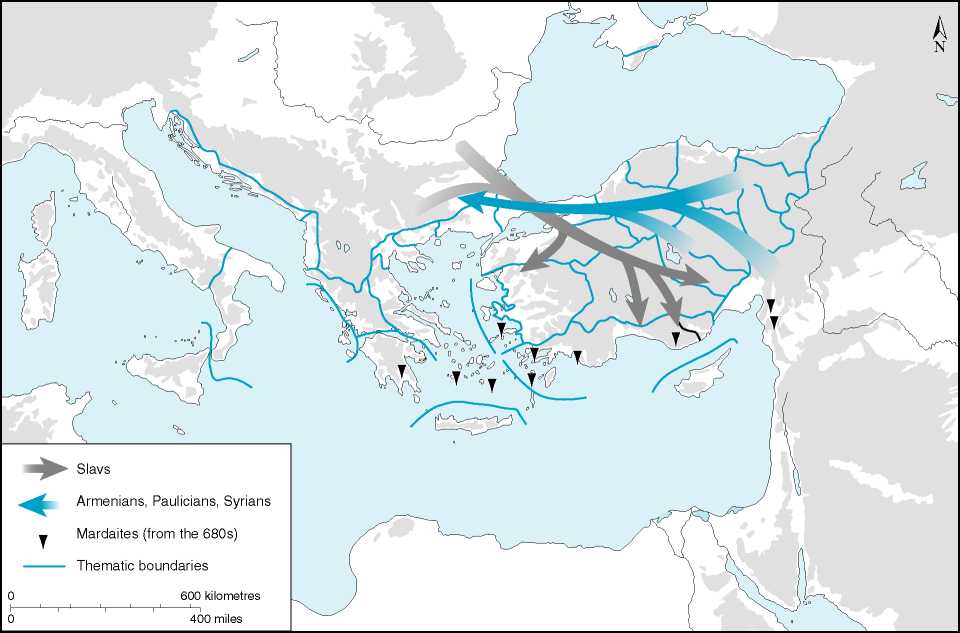

In its efforts both to cope with demographic and fiscal problems, as well as to eradicate religious opposition, and from the later sixth century and well into the ninth century, the government followed a policy of moving populations - sometimes in huge numbers - from parts of Asia Minor to the Balkans, especially southern Thrace, in order to re-populate that devastated region. The first large-scale transfer seems to have been under Maurice, when arrangements were made to settle a number of Armenian soldiers and their families in Thrace in order to boost the number of potential recruits for the army in the impoverished and devastated Balkan provinces. Apparently on a much grander scale, the Emperor Constans II moved large numbers of captive Slavs into Asia Minor, a precedent also followed by the Emperor Justinian II. Of these, the latter recruited his own special army from the settlers in 690 or 691, but it proved unreliable when put to the test of battle, many of the soldiers deserting to the Arabs or running away. Further transfers of population from the Balkans to Asia Minor took place under Constantine V as a result of the captures made during his campaigns into Bulgaria, and on at least two occasions, in 759 and in 762. These efforts reflect the destruction wrought by the constant incursions of the Islamic raiders, and the need felt by the central government to stabilise the situation. The Slav populations of Bithynia in north-western Asia Minor retained an identity as such for several centuries thereafter.

The movement was not all in the same direction. Justinian transferred the Mardaites from the Lebanon to the Balkans and Asia Minor. The Mardaites were a warlike people who had caused particular difficulties for the Caliphate, and were removed under treaty in the 680s; and a considerable number of people were removed from the region around Germanikeia in northern Syria under the same emperor, to be settled in Thrace. In the mid-750s Constantine V settled considerable numbers of forcibly removed emigrants from north Syria and the Anatolian region in Thrace, and this appears to have caused the Bulgar leadership some concern, no doubt increased when Constantine constructed a chain of fortresses and forts to protect them. At the same time, the emperor seems to have pursued a deliberate policy of depopulating the frontier zones to establish a no-man’s land through which smaller raiding parties would pass with difficulty. Imperially-decreed transplantations of populations from the north Syrian frontier region occurred in 745/746, for example, after a successful attack on Germanikeia. These people, reportedly mostly Monophysite in belief, were removed to Thrace; similar deportations occurred in 750-751 and 754-755 from the regions of Melitene and Theodosioupolis. The policy served both to strengthen the no-man’s-land of the north Syrian border zone and the Christian population in Thrace, which had suffered from Slav and especially Bulgar raids and attacks. Large numbers from the same regions were again seized and transferred to the Balkans under Leo IV after an expedition in 776, and Constantine VI deported mutinous

Map 6.7 Population movement c. 660-880.

Soldiers from the Armeniakon thema to the western provinces in 793. Michael I (811-813) deported heretical members of the sect of the Athinganoi to western provinces also.

The transfers affected not just captives, however: under Nikephoros I many soldiers from Asia Minor registered on the military rolls of their region were forced to move to Thrace, with their families, for similar reasons. Under Basil I again the defeated Paulicians were removed in considerable numbers from eastern Anatolia to the Balkan provinces, to which they brought their own version of a dualist heretical system which, on new ground, seems to have prospered and eventually given rise in the Bulgarian territories during the tenth century to Bogomilism. During the eleventh century and after there was a large-scale migration of Syrians and especially Armenians into south-western Asia Minor, partly a result of imperial expansion eastwards in the tenth century, partly a result of the Seljuk threat in the middle of the eleventh century.

This policy, carried on intermittently over some four centuries, had the effect of introducing significant changes into the demographic and cultural composition of many provinces (and also the placenames of some regions), and it emphasised the multi-ethnic character of the orthodox Byzantine state. It may also have played no small part in the continued flexibility of the empire when faced with substantial economic and military challenges from its enemies over the same long period. But the changing demographic structure of the east Roman state was not all a result of official policy, or at least of compulsory transfer. Considerable numbers of Goths, for example, settled by treaty agreement in north-western Asia Minor during the fifth century, and this group was strengthened by further additions of soldiers and their families in the later sixth century, probably making up the division of the Optimatoi in the Opsikion army, represented perhaps also by the so-called Gotthograikoi (Goth-Greeks) who appear in this region in the early eighth century and who had their own fiscal administrator. Many soldiers of the army of Illyricum were likewise settled in the same region, to become part of the imperial field army in the first half of the seventh century and later constitute a separate thema. The ethnic make-up of Asia Minor was further complicated by the arrival and settlement in the eleventh century of small numbers of Frankish mercenaries and their families and, much more significantly, of the nomadic Turkmen.

World History

World History