It has been suggested (by Michael Roberts in A Revolution in Warfare) that this period saw a ‘catastrophic’ diminution in infantry firepower through the introduction of infantry firearms, and others have implied something similar. Any view which suggests that, over a century and a sub-continent, virtually all governments spent vast sums reducing the effectiveness of their armed forces, must be open to question, and the facts do not seem to support this one. In Europe, the only earlier weapon which had any claim to outperform firearms was the longbow, which only one nation used, nor was it probably as effective in practice as ‘best’ rates of fire and ranges would seem to suggest. Even at its peak, the longbow required stake barricades and support from dismounted men-at-arms against cavalry, just as the firearms of our period required the support of pikes.

A Polish writer similarly suggests that the replacement of crossbows among the Polish infantry with firearms reduced their firepower to 1/40th of what it had been, but again available information on the performance of crossbows and firearms does not support this.

Of the earlier, pre-gunpowder weapons, there were three of any significance, not counting javelins or ‘darts’, which were used by Irish and Eastern irregular infantry as well as various light cavalry.

The Longbow

The traditional English weapon; though the last great battle in which it was the sole weapon was Flodden, up to the 1560s most English shot were still archers, especially on the Border, where the bow was preferred to the heavier and clumsier arquebus. Statutes to promote the use of the bow (and discourage evil substitute recreations such as shove-ha’penny) were passed up to 1569. After 1589 archers were dropped from the standard company organisation, and they had officially disappeared by the 1590s, though there are a few signs of their use in England in the early 17th Century.

Longbows were often of yew, six foot to six foot four inches overall, and fired arrows up to 37 inches long (though the only surviving example, which comes from our

Period, is 30V2 inches).

There has been much debate about the performance of the longbow, but it would seem that the absolute maximum range, using the lighter ‘flight’ arrow (which was used in battle, there being usually eight light arrows in each ‘sheaf of 24), was around 300 yards; with the heavier sheaf arrow used for armour-piercing it would be more like 170 yards, while to be accurate against individual targets or to pierce mail it would come down to 80 or 100 yards. The weak points of plate armour could only be picked out at very close range.

The high rate of fire of the longbow was one of its chief advantages — up to six shots a minute was certainly possible, and this was far above the performance of contemporary firearms (in fact Ben Franklin thought the American army of the 18th Century would do well to go back to the longbow). Its decline in the 16th Century seems hard to explain in view of this very good performance, but one basic cause would appear to have been a growing lack of really well-trained archers — it took a lifetime to make an archer, a few weeks at most to train an arquebusier.

The other major factor, one easy to overlook, is that this is essentially a case of mechanisation — perhaps the earliest example of a major substitution of chemical for muscle-power; a longbow had a pull of some 80 pounds, and the performance of the bow depended entirely on the strength of the archer, whereas a puny and exhausted arquebusier could shoot just as hard and far as a fresh one. Sir Roger Williams wrote that not one in five was ‘a good strong archer’, and after three or four months’ campaigning, not one in ten. Lesser problems were the difficulty of getting fresh ammunition supplies, and the fact that bowmen had to expose themselves to enemy fire when shooting from entrenchments; an advantage was cost — bow with arrows 6s 8d, caliver 16s 8d!

Certainly the longbow in practice seems to have made a fairly poor showing against firearms; the French captain Monluc, for

Crossbows and a German crossbowman of the early 16th Century, showing firing position.

German two-handed swords (Tower of London).

Two arquebusses. Above An early model. Below A 17th Century matchlock heavy arquebus. Both in the Tower of London.

Example, claimed that his men had acquired an exaggerated idea of English courage because archers had to approach so close in order to fire! Even enthusiasts for the bow had to admit that Frenchmen and Reiters in battle were apt in contempt to 'turn up their tails and cry: “shoot English!”,' though maintaining that an archer of an earlier generation would have had ‘the breech of such a varlet nailed to his bum with one arrow, and another feathered in his bowels, before he should have turned about to see who had shot the first’.

In the late 15th Century the French still used the longbow, which they had adopted earlier, to some extent, and similar bows were used by the Scots and the Irish (in the former case being used well into the 17th Century).

The composite bow

The traditional weapon of the East, used by the Turkish infantry at least to the 1680s, and by their cavalry and other Eastern horsemen until much later times. Constructed of laminated horn, horn and wood, or later apparently sometimes of metal, this type of bow was very effective. With halfounce flight arrows distances of over 600 yards could be achieved, but these were not employed in war, and with the two-ounce, 24 inch war arrow, range would be much reduced — an Arabic archery manual of the period says 175 yards, but Sir Ralph Payne-Galway states that a three-foot composite bow had a 118 pound pull, would shoot a war-arrow up to 300 yards, and would pierce a half-inch plank at 100 yards; for accuracy and armour-piercing, range would be similar to a longbow, and rate of fire would be at least as good.

The crossbow

Crossbows were still in very widespread use at the beginning of this period; found in nearly all European armies, they were used both in siege warfare and, by skirmishers, in battle. They were gradually replaced by firearms, which had much the same sort of performance. Marignano (1515) was the last battle in which they played an important role, though the French infantry preferred them to guns until at least 1523, and some remained in use up to the 1560s.

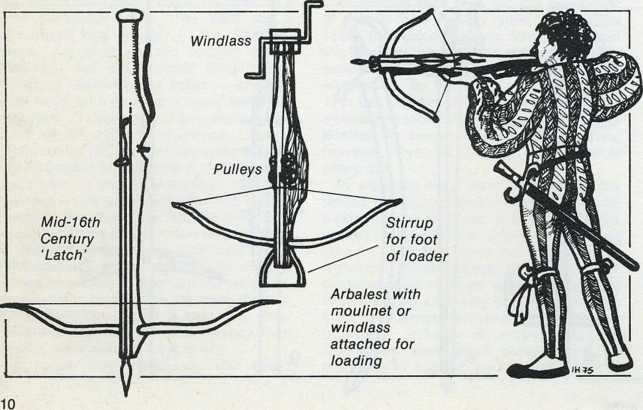

The usual 16th Century type was the heavy ‘arbalest’, which had a steel bow (often blued) and wooden rifle-type stock, and was ‘spanned’ or drawn with the aid of a separate windlass. Lighter types or ‘latches’, spanned with a lever, or a ratchet rather like a car jack, were also in use and would probably have been used by the mounted crossbowmen who were popular during the Italian wars.

The arbalest was as fjeavy as a gun (the bow could weigh nine pounds, the windlass another five pounds) and almost as slow-firing, at one or two rounds per minute. Like an arquebusier, the crossbowman could take cover behind a wall or parapet, and benefit by resting his weapon on it while firing.

A crossbow was very accurate up to some 60 yards, and might have an absolute maximum range of nearly 400 yards; the armour-piercing performance of its short, heavy bolts, while probably not up to that of firearms, would be much better than the other bows, especially against plate.

World History

World History