A Latin psalter, which is the most significant illustrated manuscript produced in the kingdom of Jerusalem in the twelfth century (MS London, British Library, Egerton 1139).

The psalter is usually attributed to the patronage of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem (1131-1152), on several grounds. A luxury manuscript, it can only have been produced for a very high-ranking individual, who must have been a woman, according to the formulation of the prayers. The only other possible candidate is Melisende’s sister Yvette, abbess of the convent of St. Lazarus at Bethany, but Lazarus’s name does not appear in the calendar. Also the litany before the prayers is written for a layperson. Though it is undated, the psalter is presumed by most scholars to have been produced between 1131 and 1143. Supporting this dating is the fact that neither the dedication of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (1149) nor the death of Melisende’s husband, King Fulk (1143), is mentioned in the calendar. Among those who are commemorated in the calendar, however, are Melisende’s parents, King Baldwin II of Jerusalem (d. 1131) and her mother Morphia, an Armenian princess. The taking of Jerusalem in 1099 during the First Crusade is also commemorated.

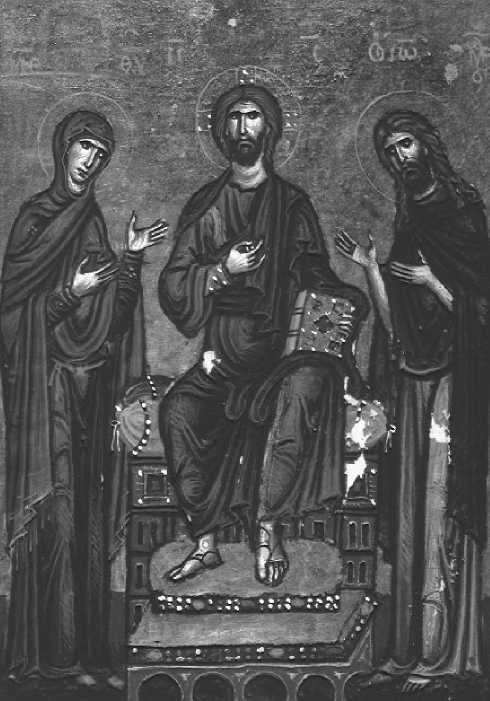

The book, comprising 218 folios and measuring 21.6 by 14 centimeters (c. 81/2 by 51/2 in.), is the work of several artists and craftspeople; the scribal work is attributed to a northern French scribe. Accordingly, the book gives an insight into the collaborative working practices of the scriptorium of the Holy Sepulchre and the diverse manuscript resources it had at its disposal. The book opens with twenty-four full-page miniatures of New Testament scenes collected together at the front of the book, preceding the psalter text. Although the artist who painted the New Testament scenes signed his name (Basilius) in Latin on Christ’s footstool in the Deisis picture (see figure), many of the features of his work are Byzantine or Eastern Christian. These include the

The Deisis from Queen Melisende’s psalter, twelfth century. (By permission of the British Library)

Byzantine intercessionary image of the Deisis image itself, painted in bright contrasting colors against a gold background. A second artist produced the eight full-page ornamented pages that mark the liturgical divisions of the text. Here the initial letter of the first word is drawn in black ink on a gold ground, with the few following lines written in gold on purple. The rich patterning effect in several of the designs is reminiscent of metal work from Edessa (mod. fianliurfa, Turkey) in Upper Mesopotamia. These Eastern and Western elements could be seen as being reconciled in the person of Melisende herself, whose Armenian mother, Morphia, was a Melkite Orthodox Christian from Melitene (mod. Malatya, Turkey). Given her background and political sympathies toward Eastern Christians, it is quite possible that the second artist of the psalter and even Basilius himself were Eastern Christians. Melisende’s befriending of

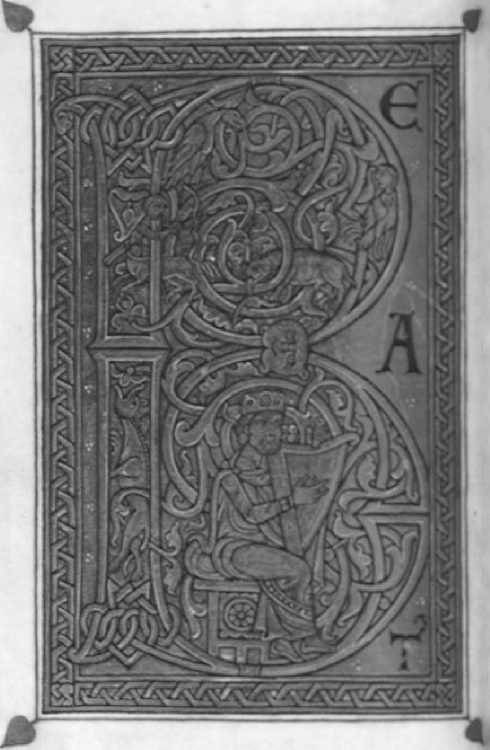

Initial B of Psalm 1 from Queen Melisende’s psalter, twelfth century. (By permission of the British Library)

Refugees from Edessa and defense of the property rights of indigenous Christians, including Syrians, in Jerusalem is consistent with this. But other motifs employed in the manuscript’s decoration are Romanesque and can be traced to the medieval West. The B of the Beatus initial of Psalm 1 (see figure) shows King David playing his harp, surrounded by climbing figures of animals and a bird within foliage with, in the upper part, a siren being shot at by a centaur-sagittarius. There are gold initials throughout the text of the psalter. The calendar, listing saints and church feasts, is English, not Jerusalemite, in origin. Unusually, it celebrates the name of the French saint Martin of Tours in golden letters. It is adorned with medallions, one for each month of the year, with the signs of the zodiac. The prayers at the end of the book emphasize veneration to the Virgin Mary and St. Mary Magdalene, as well as to the cross. This has prompted the suggestion that the book was associated with the abbey of St. Mary of Jehosaphat in the Kidron Valley outside Jerusalem, of which Melisende was a benefactor. She was perhaps a member of its noble lay confraternity and was ultimately buried there, as had been her mother. A fourth artist completed the psalter’s illustration with portraits of standing saints illustrating the prayers. The manuscript has an embroidered silk binding on the spine. Small red, green, and blue crosses are sewn onto the silver embroidered off-white Byzantine silk.

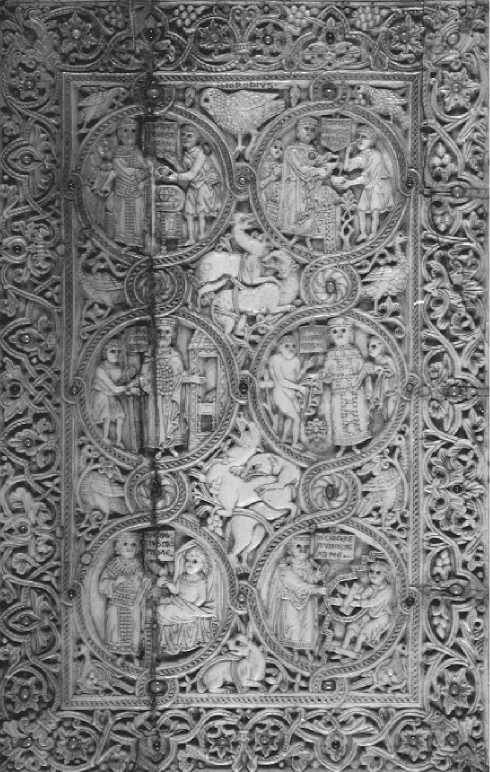

The original ivory covers of the book, also housed in the British Library, were carved in Jerusalem. These retain traces of polychromy and gilding, with precious stones in the eyes of some figures and in the borders. The covers are carved with scenes appropriate to kingship, providing the Christian and moral justification for Latin rulership. The front cover depicts scenes from the life of King David from the Old Testament, in roundels. Occupying the interstices between these are female personifications of virtues overcoming vices, the subject of a Latin poem, the Psychomachia by Prudentius. The reverse (see figure) shows the six Acts of Mercy of St. Matthew’s Gospel (25:35-36), each performed by an emperor in Byzantine ceremonial dress, with animals and birds in the interstices.

The presence of the falcon (Lat. fulica) labelled Herodius at the top of the panel is generally accepted as providing identification with Melisende’s husband King Fulk, formerly count of Anjou. It has even been suggested that Fulk presented the book to Melisende within a couple of years of their reconciliation, which had taken place late in 1134. This theory is based on the presence of Fulk’s rebus on the back cover, as well as the several French and English features in the manuscript. It does, however, problematically presuppose the replacement of Melisende as the prime mover behind the commissioning of the manuscript. If Fulk was indeed involved in this way, given Melisende’s assertive personality, it is likely that the commission was a genuine collaboration between them. The subsequent influence of the Melisende Psalter was considerable, particularly on Eastern Christian manuscript illumination, as in the case of the Syriac lectionary in MS Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, syr. 355, illustrated in Melitene at the turn of the thirteenth century.

Lucy-Anne Hunt

Ivory cover (back) from Queen Melisende’s psalter, twelfth century. (By permission of the British Library)

See also: Art of Outremer and Cyprus

Bibliography

Boase, Thomas S. R., “Mosaic, Painting, and the Minor Arts,” in A History of the Crusades, ed. Kenneth M. Setton et al., 2d ed., 6 vols. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969-1989), 4:117-139.

Buchthal, Hugo, Miniature Painting in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem (Oxford: Clarendon, 1957).

Folda, Jaroslav, The Art of the Crusaders in the Holy Land, 1098-1187 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Hunt, Lucy-Anne, “The Syriac Buchanan Bible in Cambridge: Book Illumination in Syria, Cilicia and Jerusalem of the Later Twelfth Century,” Orientalia Christiana Periodica 57 (1991), 347-348; reprinted in Lucy-Anne Hunt,

Byzantium, Eastern Christendom and Islam: Art at the Crossroads of the Medieval Mediterranean, 2 vols. (London: Pindar, 2000), 2:39-41.

Kuhnel, Bianca, “The Kingly Statement of the Bookcovers of Queen Melisende’s Psalter,” Tesserae: Festschrift fur Josef Engemann, ed. Ernst Dassmann (Munster: Aschendorff, 1991), pp. 340-357.

Norman, Joanne S., “The Life of King David as a

Psychomachia Allegory: A Study of the Melisende Psalter Bookcover,” Revue de l’Universite d’Ottawa / University of Ottawa Quarterly 50 (1980), 193-201.

World History

World History