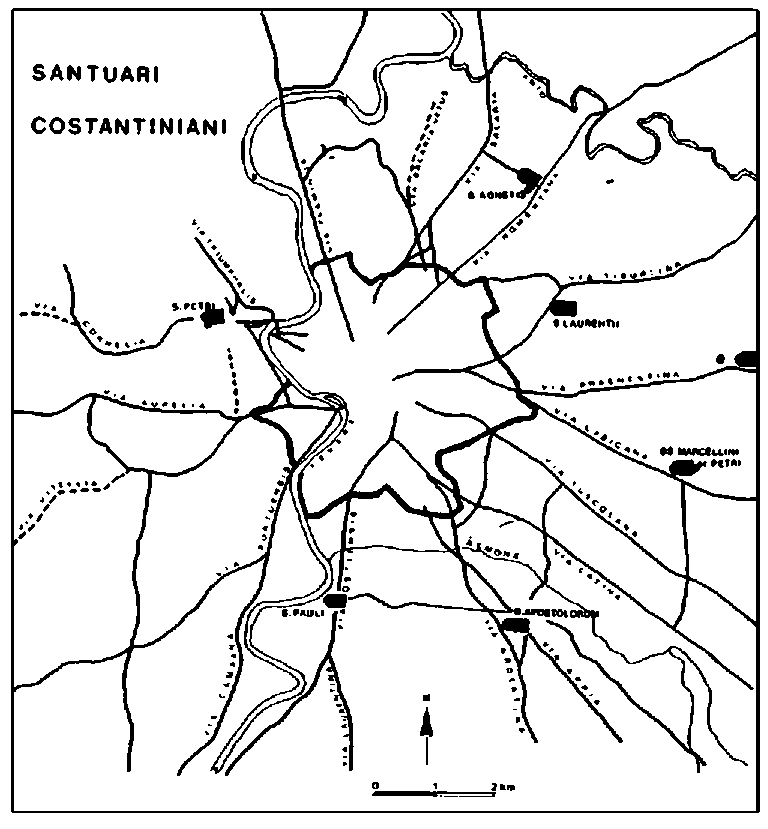

The desire to emulate, indeed to surpass, the games in celebrating the martyrs may find its expression in one peculiar characteristic of Roman ecclesiastical architecture of the Constantinian and post-Constantinian periods. The suburban martyrs’ basilicas, and only these (apart from St. Peter and St. Paul), are based on a ground-plan resembling a circus (fig. 28.2). In addition to those mentioned above, the Basilica of Mark on the Via Ardeatina and that of Agnes on the Via Nomentana belong to the late or post-Constantinian basilicas with ambulatory. The latter was dedicated to the “Victrix Agnes,” according to the inscription that records its consecration (ICUR NS 8.20752). The anonymous ambulatory basilica on the Via Praenestina and the “Basilica of the Apostles” (St. Sebastian) were erected at imperial villa complexes containing a stadium (the church of St. Peter also lay at the site of an abandoned circus).

The seemingly circus-shaped ground-plan of the basilicas with ambulatory can hardly be understood by referring to a cosmological symbolism of eternity. It is more likely that the martyrs’ basilicas are to be placed in the context of the heroes’ cult of imperial times. This cult was connected in particular to places of athletic contest, in so far as Hercules was regarded as the patron of athletes. The Christians accordingly publicized their heroes, the martyrs, in circus-shaped churches (La Rocca 2002).

Figure 28.2 Constantinian church buildings outside the gates of Rome (Pani Ermini 1989: fig. 4).

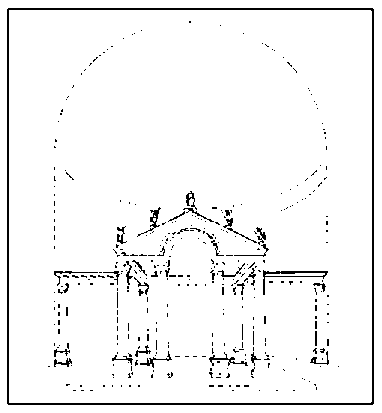

Such Christian borrowings from the heroes’ cult cannot, however, be proven. The basilicas in honor of the martyrs were without doubt intended as architectural expressions of triumph. All of Constantine’s churches express this also in architectural, and monumental, terms: the Basilica of Peter through the canopy (Ziborium) above the martyr’s tomb, the Lateran Basilica through the so-called Fastigium - a gable monument in between nave and altar room, which carried the statues of Christ and the apostles (fig. 28.3) - and the other basilicas on precisely these circus-shaped ground-plans.

Figure 28.3 Reconstruction of the presbyterium of the Constantinian Lateran Basilica (Bisconti 2000: 186).

The circus as location of victorious athletes and the basilicas as celebratory spaces for the martyr-athletes led to the idea of erecting the new churches on the ground-plan of a circus. Such a play with architecture was not unusual (Torelli 2002). The playful nature of this approach explains also why, while the entrance wall of the basilicas was placed at an angle to the main body of the building, like the section of a circus which contained the starting gates, it was at varying angles, just as this aspect was handled at will in pictorial representations of a circus.

If nothing else, this playfulness indicates a certain understanding of martyrdom. The martyr as victorious athlete had been a topos of Christian publicity from the start. “Athlete of Christ” and “Athlete of the Faith” became regular descriptions of martyrs and confessors from the third century, especially when they were paraded during circus games. The first letter of Clement, which was composed in Rome around 96, writes of the athletes of Nero’s persecutions of the Christians, who had fought the agon of life and death in the arena (1 Clemens 5-7). The apostle Peter endured many “pains,” bore witness, and reached the place of glory he merited, which in this context refers to the staging of the victor’s ceremony. Paul is also mentioned - echoing 2 Timothy 3. 10-4. 8 - whose missionary activity takes on the appearance of a contest, in that he is repeatedly taken prisoner and tortured, but finally obtains the victor’s prize.

World History

World History