Clovis was baptized after he promised his wife that he would convert to Christianity if he won an important battle. When he was successful, he also had all his troops baptized with him. Tltis 14th-century manuscript shows a bishop pouring the baptismal water over the king’s head.

Major historical events usually create traumas and drastic changes in individual lives. The Visigoths’ sack of Rome in 410 had an enormous impact on the invaders and the invaded. One Roman of patrician rank, for example, wrote to a friend complaining that the Visigoths had stolen his land, which mined him and reduced him to beggary. Strangely, some years later one of the plunderers located him and offered to pay for the land he had taken. Although the Roman claimed that he did not receive the fair market value, he confessed that the return of a part of his wealth helped him to again hold his head up in the Roman society of Gaul.

With the invasion of Rome, people lost not only land. Many lost their lives, and many others faced the possibility of marriage to people whose appearance and customs were strange.

For people living in Europe from the fifth through the seventh centuries, waves of change altered or removed many of their familiar institutions. As a result, their children had to be reared differently from the way they themselves had been. For tribes accustomed to moving to greener pastures and new forests when they had exhausted the old, becomingpart of the empire meant encountering people who lived in one place and cultivated the same land year after year. Loose tribal confederations became kingships {rex was the Roman term for their leaders); Germanic laws had to be reconciled with Roman laws; and for the Germanic tribes individual ownership of land created an entirely new concept of making a living, that is, from cultivation rather than plunder. Adding to the confusion were Roman prejudices against the Germanic tribes. The Roman population, now Christian, regarded their new neighbors as land grabbers and heretics (religious dissenters who held incorrect views of Christianity), because many of the tribes had converted to Arianism (the interpretation of Christianity that had been banned in 325 at the Council of Nicaea).

The letters and some poetry of a patrician Roman named Apolhnaris Sidonius (431— 489) provide an insight into the experiences of at least one man and his correspondents during this turbulent period. Sidonius had followed the traditional career pattern for his class. He had entered public service.

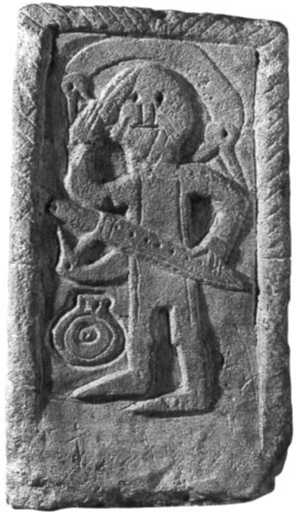

Converted tribesmen often used both pagan and Christian symbols on their tombstones. This stone has the typical double-headed serpent from pagan art; the flask at the man’s feet and the sword and comb in his hands suggest that these are pagan grave goods. The other side of the stone, however, has a representation of Christ carrying a spear.

Becoming an official in Rome. He was of such high status that he married the emperor’s daughter. After retiring to his country estates, he spent the final 17 years of his life serving as bishop of Clermont in what is now central France. As the Church became the last vestige of the old imperial system, many members of the patrician class became bishops and continued to administer both spiritual comfort and civic services to the urban population. Like many other bishops, Sidonius was charged with the task of organizing the defense of his city against the Visigoths and other tribes who besieged the countryside in the 470s. He wrote in 473; “Our own town lives in terror of a sea of tribes which find in it an obstacle to their expansion and surge in arms all around it.” When the town fell, he spent three years as a prisoner of the Goths.

Despite the sack of Rome, Sidonius continued to consider the city “the abode of law, the training-school of letters, the font of honors, the head of the world, the motherland of freedom, the city unique upon earth where none but the barbarian and slave is foreign.” But he was fully aware that the “Roman state has sunk to . . . extreme misery.” Writing to his friends, Sidonius praised his correspondents’ dedication to keeping the study of Latin and Greek alive: “The Roman tongue is long banished from Belgium and the Rhine; but if its splendor has anywhere survived, it is surely with you; our jurisdiction is fallen into decay along the frontier, but while you live and preserve your eloquence, the Latin language stands unshaken.”

Sidonius also wrote of the transformation taking place among the tribespeople. He described Sigismer, a Germanic prince, who walked at the center of a victory procession:

With charming modesty he went afoot amid his body guards and footmen, in flame-red mantle, with much glint of mddy gold, and gleam of snowy silken tunic, his fair hair, red cheeks and white skin according with the three hues of his equipment. But the chiefs and allies who bore him company were dread of aspect. . . . Their feet were laced in boots of bristly hide reaching to the heels; ankles and legs were exposed. They wore tight tunics of varied color hardly descending to their bare knees, the sleeves covering only the upper arms.

Cloaks of skins secured with brooches completed their garb.

Bishop Gregory of Tours (538—594), writing about a hundred years later, presented a very different picture of Gaul. By this time, the Visigoths had moved on into Spain, and a new tribe, the Franks, had crossed the Rhine and setded in what was once Roman territory. The area eventually took the name France from this tribe. The Franks had had little contact with Romans and had not converted to any version of Christianity. Bishop Gregory’s own world was far removed from Rome and the imperial traditions, but Christianity was strong. He wrote of his embarrassingly poor Latin, which indicates that he was not schooled by the old standards. His interests also show a shift of perspective from that of Sidonius. He recounted stories of brutal Frankish rulers and relished miraculous events rather than classical literary works. For example, Gregory wrote of an army of Franks who plundered the church of the holy St. Vincent, a martyr who died for his Christian beliefs. The troops found it filled with treasure that had been deposited by Christians who trusted in the saint’s power to save their goods. Unable to open the church, the Franks set it afire. When they tried to retrieve the goods inside, however, divine vengeance was visited on them. According to Gregory, their hands were “supematu-raUy burned, and sent forth a great smoke, like that which rises above a fire.”

Gregory also recounted the vicious politics of the Franks, who gradually seized all of Gaul. Clovis (481/2—511) emerged as the victorious ruler after many battles in which his family members were often killed. Gregory reported an emotional speech Clovis delivered before a large gathering of Franks: “Oh woe is me, for 1 travel among strangers and have none of my kinsfolk to help me!” Gregory went on to suggest that “he did not refer to their deaths out of grief, but craftily, to see if he could bring to light some new relatives to kiU.”

Clovis and the Franks, however, were set apart from other tribes by their conversion to Roman Christianity, that is, the Christian beliefs of the bishop of Rome (also known as the pope) as opposed to those of the Arian heretics. Clovis married

A Christian woman, Clotilda. Her uncle had killed her father and drowned her mother by tying a stone around her neck. Clotilda’s sister had retreated to a nunnery, and Clotilda might have followed suit if Clovis had not been taken by her beauty and married her. Gregory of Tours wrote that Clotilda immediately tried to convert Clovis to Christianity. She persuaded him to allow the first two sons she bore to be baptized, but because they died soon after birth her husband remained unconvinced about the new religion’s worth. Finally, in a battle with another tribe, Clovis looked to heaven and promised to convert if he won. After his victory, he fulfilled his promise by being baptized along with 3,000 of his followers. Clovis knew even less than Constantine about Christianity, but because he and the Franks were baptized as Roman Christians, they were loyal to the pope. Later, when the Church needed help, its leaders looked to the Franks for aid.

Clovis unified the Franks under a long-lasting dynasty, the Merovingians—a name derived from a mythical ancestor, Merowech. The Franks practiced partible inheritance—that is, a father’s lands were divided equally among his sons. Upon their father’s death, brothers would fight each other until one dominated. Each change of king, therefore, resulted in the same sorts of brutal fights between brothers in which Clovis had engaged. The queens were no less capable of bloodthirsty tactics. Despite such fighting, the Franks became a strong power in Europe. They successfully assimilated their kin from across the Rhine and encouraged missionaries to convert their brethren.

Italy enjoyed a generation of peace and order under another tribal invasion, the Ostrogoths (or east Goths). Their leader was Theodoric (reigned 471—526), who had been a hostage at the court in Constantinople and therefore was very familiar with imperial government. Although the Ostrogoths were Arians, Theodoric did not try to persuade the non-Arian population to convert. Rather than destroying what remained of the Roman Empire and Roman ways, he worked with the conquered people to restore their aqueducts, repair their buildings, and improve the general order and economy of the Italian peninsula. In return for aiding the local population and defending them against other tribes, the Ostrogoths taxed a third of the proceeds from the estates of the wealthy. This policy was kinder to the local population than the outright plunder and confiscation of goods and land that other tribes had committed.

With the establishment of a general peace between mainstream Christians and heretical Arians, between Romans and Ostrogoths, learning once again flourished in Italy. Boethius (c. 480—524), a Roman who became an official for the Ostrogoths, realized that Greek might die out as a language of learning. Thus he translated portions of Greek philosophy, including the entire works of Plato and parts of Aristotle’s writings. His translations were used throughout the Middle Ages. Cassiodorus (c. 490—585), another scholar who was close to Theodoric, retired from government service and became the abbot of a monastery. He set his monks the task of copying and preserving the works of Christianity and of pagan Greece and Rome.

Amalsuntha, daughter of a sixth-century Byzantine emperor, became regent for her young son on her father’s death. This ivory shows her holding an orb, the symbol of ruling, wearing a typical Byzantine crown and sitting on a throne surrounded by pillars to suggest a palace.

Symmachus and his son-in-law Boethius were Romans who served as officials under the Ostrogothic king Theodoric. But when the Pope began to attack the Ostrogoths for their Arian heresy, Theodoric turned against his Roman officials and they were executed.

World History

World History