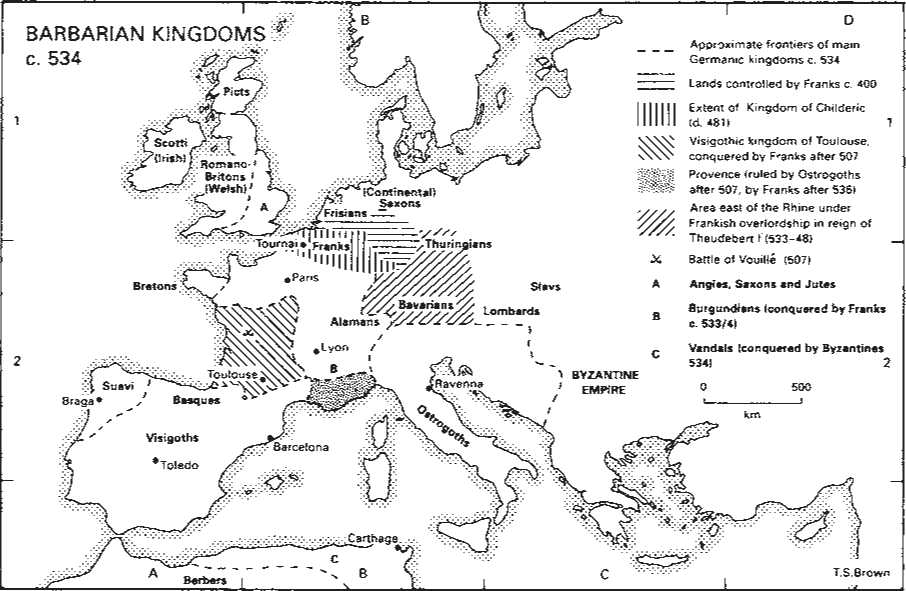

By 500 the Roman Empire in the west had been replaced by powerful Germanic kingdoms. Prominent were the Frankish kingdom built up in northern Gaul by the Frankish rulers Childeric (d. 481) and his son Clovis (481-511) and the Ostrogothic kingdom established in Italy by Theoderic (489-526). Any semblance of stability in the west was, however, shattered over the next four decades. After his victory over the kingdom of Toulouse at Vouille in 507 Clovis took over most of south-west Gaul and the Visigoths were compelled to transfer their political base to Spain, with their eventual capital at Toledo. The kingdom of their Ostrogothic cousins fell into decline on Theoderic's death as a result of dynastic uncertainties and tension between proRoman and traditionalist elements. Two of the initially powerful kingdoms were conquered in 533-4: the Burgundians' territories in south-east Gaul were incorporated by the Franks and Van

Dal rule in North Africa was ended by the lightning campaign of the Byzantine general Belisarius. In 534 the Ostrogoths became the next target of the emperor Justinian's dream of restoring Roman power in the west and Belisarius' forces invaded Italy in 536. Despite fierce resistance by a Gothic army in the north led by Witigis, Belisarius occupied Ravenna in 540. In the 540s the tide turned, thanks to the divisions and corruption of the imperialists, and the able Gothic ruler Totila was able to claw back most of the peninsula. By 552, however, new forces dispatched from the east under Narses defeated the Ostrogothic army. Nevertheless,

Isolated pockets of Gothic resistance held out in the north until the 560s and Italy lay devastated by years of war. Justinian's attempted reconquista of the west went a step further in 551, when an enclave around Cartagena was seized from the Visigothic kingdom of Spain and remained Byzantine until the 620s. However, economic weaknesses and new pressure from the Avars, Slavs and Persians prevented Byzantium from consolidating its gains, and most of Italy was lost to the Lombards from 568. The dominant power in the west became, not the empire, but its nominal ally, the Catholic kingdom of the Franks.

T. S.Brown

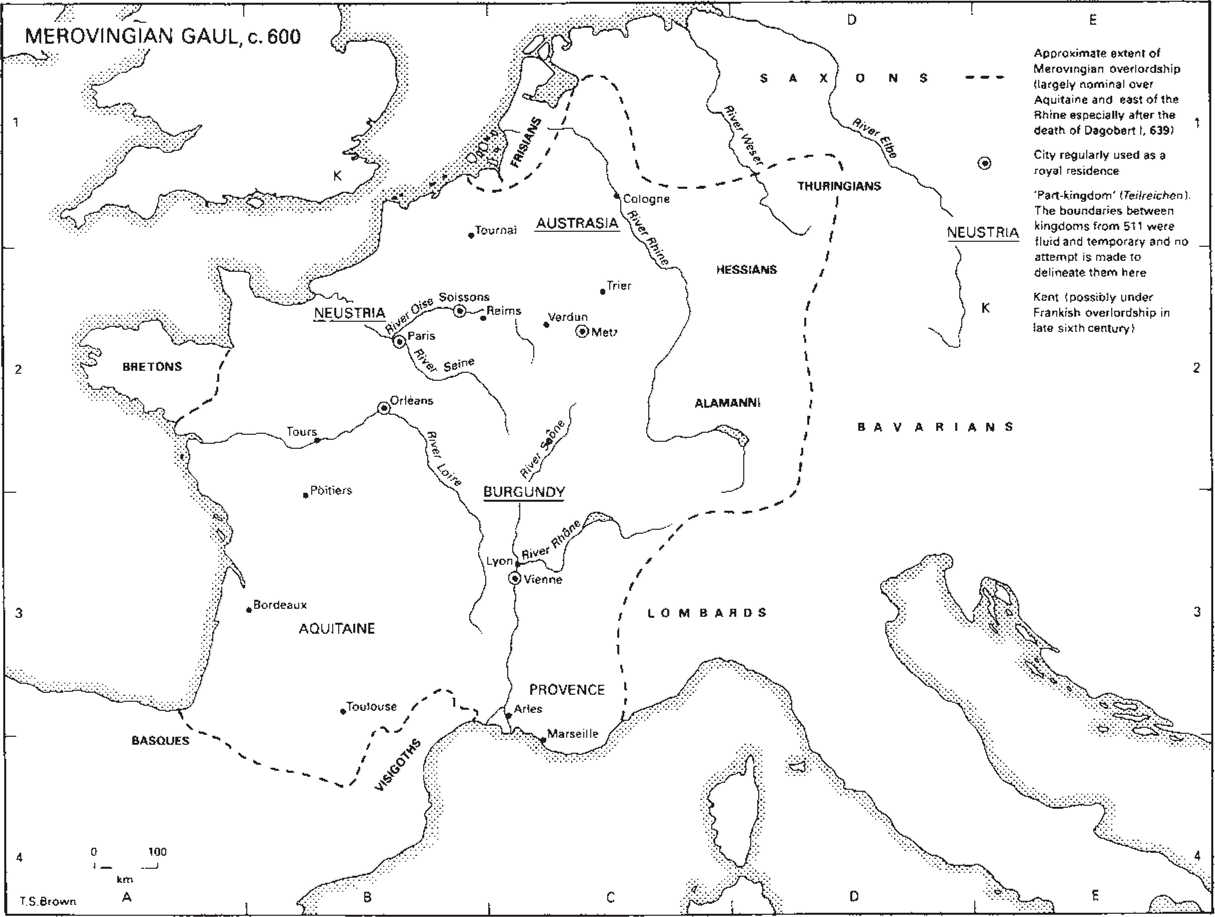

Merovingian Gaul, c. 600

Although Clovis had extended the Merovingian kingdom over most of Gaul, for much of the sixth and seventh centuries it was beset by the strife vividly chronicled by the historian Gregory of

Tours (d. 594). In 511 a complex division took place between Clovis' four sons, which ham pered efficient royal administration. The Burgundian kingdom was taken over in 534

And Provence in 536. Theudebert I (533-48) expanded his territory east of the Rhine and even beyond the Alps, but this overlordship collapsed after his death. The kingdom was then reunited under Clothar, but partition between his four sons on his death in 561 soon led to civil war and an increasing sense of identity within each Teilreich (part-kingdom).

The murder of King Sigibert of Austrasia in 575 provoked bitter conflict. For several decades the dominant force was Sigibert's widow, the Visigoth Brunhilda, but in 613 she was executed and the kingdom was reunited under Clothar II of Neustria (584-629). His son Dagobert I (62338) proved the last effective Merovingian ruler, as royal power was undermined by the alienation of rights and estates, the loss of Byzantine subsidies and tribute from client peoples east of the Rhine and the growing power of counts and other territorial magnates. Subsequent Merovingian 'do-nothing kings' were incapable of ruling personally and power fell into the hands of aristocratic factions led by the mayors of the palace, such as the Arnulfings, the hereditary mayors of the palace of Austrasia. Under Pepin II this family capitalized on its powerful following in the north-east and its alliance with the Church to become the dominant force throughout the kingdom from 687. A serious revolt followed Pepin's death in 714 but effective power over Neustria and the Merovingian puppet-kings was restored by his illegitimate son Charles Martel (d. 741), who enhanced the power and prestige of his dynasty (the Carolingians) by his campaigns against Saxons, Alamans, Thuringians and Bavarians and most famously by his defeat of an Arab invading force at Poitiers in 733.

The conflicts of the Merovingian period should not obscure its achievements. The kingdom remained the most powerful force in the west as a result of its military strength, its relatively centralized structures, a number of centres of religious and cultural life, and the assimilation which occurred between a small Frankish elite and Gallo-Roman elements prepared to adopt Frankish laws and customs.

T. S.Brown

World History

World History