Born into a rich family of cloth merchants of Assisi, Francis in his early twenties had a conversion experience that pushed him to attempt the apostolic life (Lat. vita apos-tolica), based on absolute poverty. He founded the Order of the Friars Minor, or Franciscans, who saw mission to infidels, and particularly to Muslims, as an integral part of the renovation of Christendom and of the living out of the vita apostolica.

Francis’s hagiographers affirm that he wished to live like the apostles, who preached to infidels, and to die like the apostles, martyred by infidels. It was this thirst for martyrdom, according to Franciscan hagiographers Thomas of Celano and Bonaventure, that drove Francis to embark for Outremer in 1212 in order to preach to Muslims, but contrary winds kept him in Italy. He subsequently set out for North Africa, but fell ill in Spain and did not reach Muslim territory. He finally set out for Outremer in 1219 and made his way to the camp of the crusaders who were then besieging Damietta in the course of the Fifth Crusade (12171221). Thomas of Celano tells how Francis preached in the crusaders’ camp and predicted a defeat in battle, a warning that went unheeded. Some historians have seen this incident as a testimony to Francis’s opposition to crusade or even his pacifism, yet there is no evidence to support this claim: according to Thomas, Francis warned against fighting on one ill-fated day; he did not preach against crusading in general.

Francis’s goal in coming to Egypt was to preach to al-Kamil, the Ayyubid sultan. According to the writer James of Vitry, Francis “came into our army, burning with the zeal of faith, and was not afraid to cross over to the enemy army. There he preached the word of God to the Saracens but accomplished little” [Lettres de Jacques de Vitry 1160/70-1240, eveque de Saint-Jean d’Acre, ed. R. B. C. Huygens (Leiden: Brill, 1960), no. 6]. In his Historia Occidentalis, James embellishes the incident, affirming that the sultan listened eagerly and attentively to Francis. Franciscan hagiography and iconography developed the encounter in ever greater detail, having Francis propose a trial by fire with the “Saracen priests,” or even having him secretly convert the sultan.

Francis returned to Italy without having gained the palm of martyrdom. The following year (1220), five Franciscan friars succeeded, through repeatedly preaching against Islam and Muhammad in mosques and public squares in Seville and Marrakesh, in provoking the Almohad caliph al-Mus-tansir into having them put to death. Francis, upon learning of their martyrdom, is said to have proclaimed, “Now I can truly say that I have five brothers!” [Arnauld de Sarrant,

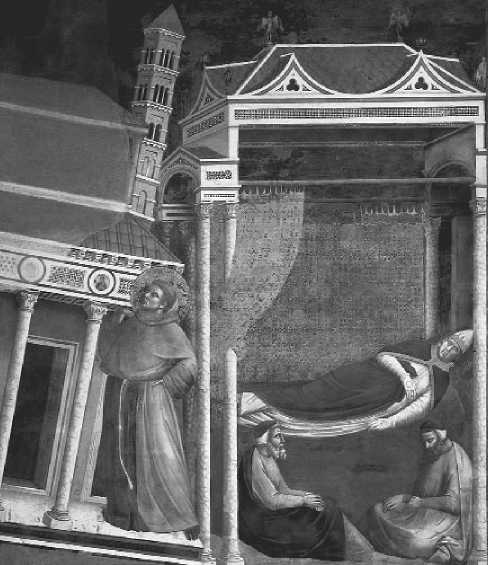

Innocent III Dreaming of St. Francis Holding Up the Church, by Giotto di Bondone, c. 1290-1295. (Archivo Iconograpfico, S. A./Corbis)

Chronica XXIV Generalium Ordinis Minorum, in Annales Franciscanorum 3 (1897), 593]. Such missions were encouraged by the earliest extant version (1221) of the rule of the Friars Minor, the so-called Regula non bullata (or Regula Prima). A chapter of the rule encouraged those friars who were spiritually prepared to undertake mission among Saracens and other infidels and urged them not to fear death. Many Franciscans heeded these injunctions: over the course of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, scores of them died at the hands of Muslims and other non-Christians throughout North Africa, the Near East, and Asia.

-John Tolan

Bibliography

Ajello, Anna, La Croce e la spada: I Francescani e l’Islam nel Docento (Roma: Istituto per il Oriente, 1999).

Hoeberichts, J., Francis and Islam (Quincy, IL: Franciscan Press, 1997).

House, Adrian, Francis of Assisi (London: Chatto & Windus, 2000).

Tolan, John V., Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002).

World History

World History

![The General Who Never Lost a Battle [History of the Second World War 29]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432581983_1425486253_part-29.jpeg)