In spite of the recovery of the imperial capital by the emperors of the Nicaean state, and the consolidation and temporary recovery of some territory in Asia Minor, the last two centuries of Byzantine rule represent a story of slow but inevitable contraction. By the middle of the fourteenth century the empire had been reduced to a dependency of the growing Ottoman Sultanate. Under Michael VIII (1259-1282), the empire was able to expand into the Peloponnese and to force the submission of the Frankish principalities in the region; in international politics alliances with Genoa and the kingdom of Aragon and, briefly, with the papacy, enabled Byzantium once more to influence the international scene and to resist the powers which worked for its destruction and partition. But under Andronikos II (1282-1328), the empire was unable to meet the challenge of a much less friendly international environment. Indeed, with the transfer of imperial attention back to Constantinople the Asian provinces were neglected at the very moment that the Mongols weakened Seljuk dominion over the nomadic Turkmen (Turcoman) tribes, allowing them unrestricted access to the ill-defended Byzantine districts. Most of the south-western and central coastal regions were lost by about 1270, and the interior, including the important Maeander valley, had become Turkish territory by 1300. Independent Turkish principalities or emirates, including the fledgling power of the Ottomans, posed a constant threat to the surviving imperial districts. By 1315, the remaining Aegean regions had been lost, and Bithynia had succumbed by 1337. In addition, the mercenary Catalan Grand Company, hired by Andronikos II in 1303 to help fight the Turks and other enemies, turned against the empire when its demands for pay were not met and, after defeating the Burgundian duke of Athens in 1311, seized control of the region, which it held until 1388. Other mercenary companies behaved similarly. The empire’s resources were simply insufficient to meet any but the smallest hostile attack on its territory, and it was rapidly losing even the possibility of hiring mercenaries.

By the time of Andronikos’ death in 1328, the empire held only a few isolated fortress-towns. With the loss of the semiautonomous region about Philadelphia in 1390 to the Ottomans, the history of Byzantine Anatolia comes to an end. The situation was greatly exacerbated by the civil wars which rent the empire in the period after the death of Andronikos II, wars which were for the greater part inspired by the personal and family rivalries of a small group within the Byzantine aristocracy. Andronikos III rebelled against his grandfather Andronikos II in 1321, and after four years of squabbling, marching and countermarching, succeeded in becoming co-emperor in 1325. Conflict flared up again in 1327, but Andronikos II died in 1328 leaving the empire to his grandson, who ruled until 1341. It broke out again in 1341, when the regency representing the young John V, son of Andronikos III (dominated by the dowager Empress Anna of Savoy and the Grand Duke Alexios Apokaukos) declared John Kantakouzenos an enemy of the empire.

John was Grand Domestic and had been the leading minister under the previous emperor; he now had himself proclaimed emperor and assembled an army. The situation was complicated by religious and social divisions. The rise of hesychasm, a mystical and contemplative movement which found particular support in monastic circles, had polarised opinion within the church, since much of the regular and higher clergy, including the patriarch, were fiercely opposed to its teachings. The regime at Constantinople thus found that the hesychasts, particularly on Mt Athos, the centre of Byzantine monasticism, allied themselves with John Kantakouzenos, who thus gained the support of Gregory Palamas, one of the greatest theologians of the last centuries of Byzantium, a leading proponent of hesychasm, and a powerful speaker. At the same time, the regency whipped up discontent in the provincial towns against the fundamentally aristocratic party led by Kantakouzenos, so that popular movements sprang up and expelled many of the latter’s supporters, with the result that Kantakouzenos fled to the Serbian king Stefan (Uros) IV Dusan (1331-55). This alliance suited Serbian expansionist interests, but did not last long; for John then allied himself with the governor of Byzantine Thessaly, John Angelos, a practically autonomous region. In response, Dusan negotiated an alliance with the regime at Constantinople. Using Turkish allies, Kantakouzenos prosecuted the war until 1345; and following the collapse of the regency and the murder of Alexios Apokaukos, he had himself crowned John VI at Adrianople in 1346 and entered Constantinople the following year, where his coronation was repeated by the patriarch.

John’s victory meant also the victory of hesychasm, which was opposed to any compromise with the western church. From 1351, when hesychast doctrine became the official doctrine of the Byzantine Church, its conservative anti-western values came to the fore and proved an important influence on the last century of Byzantine culture and politics, especially in respect of attitudes to western culture and Christianity. Politically and

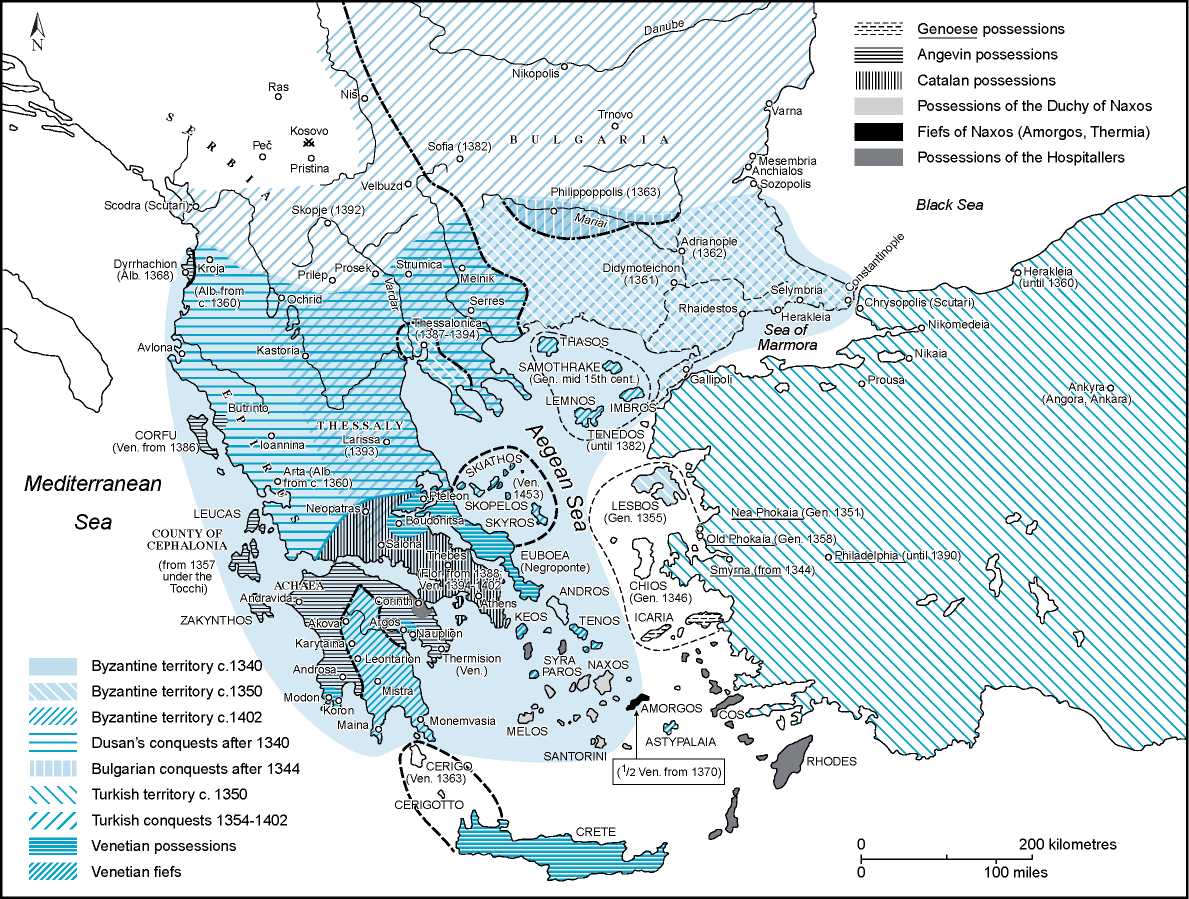

Map 9.4 Recovery, civil war, contraction 1261-1351.

Economically the empire was now in a desperate situation. The Serbian ruler Stefan IV Dusan had exploited Byzantine weakness to swallow up Albania, eastern Macedonia and Thessaly. The empire was left with Thrace around Constantinople, a small district around Thessalonica, surrounded by Serbian territory; together with its lands in the Peloponnese and the northern Aegean isles. Each of these regions was, in practice, a more-or-less autonomous province, constituting together an empire only in name and by tradition. But the civil wars had wrecked the economy of these districts, which could barely afford the minimal taxes the emperors demanded, a point well illustrated by the fact that the Genoese commercial centre at Galata, on the other side of the Golden Horn from Constantinople, had an annual revenue seven times as great as that of the imperial city itself.

Decline and Fall 1350-1453

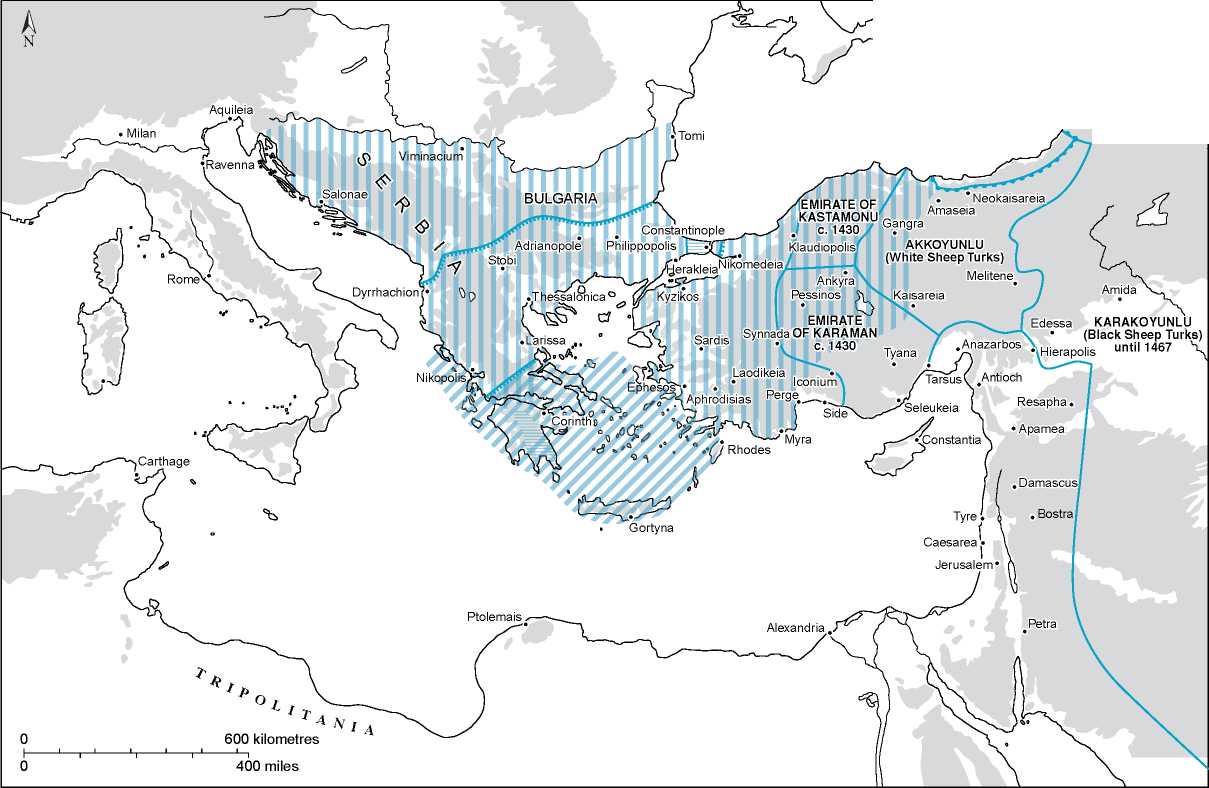

From the 1350s a new European enemy appeared, for the Ottomans had expanded into Europe during the civil wars, following a request in 1344 from Kantakouzenos for Ottoman help against John V. As a result, they began permanently to establish themselves in Europe, taking the chief towns of Thrace in the 1360s, and Thessalonica in 1387. By about 1400, and with the exception of imperial territory in the southern Peloponnese (the despotate of the Morea) and certain Aegean islands, the empire had no lands in Greece.

The complex territorial and political history of the empire after 1204 reflects the vested interests and factional divisions of the western powers which had been directly involved on the Fourth Crusade. Much of the southern part of the Aegean came under Venetian authority; and although Byzantine power was re-established briefly during the later thirteenth century, Naxos remained the centre of the Latin ‘duchy of the Archipelago’, established in 1207 in the Cyclades by Marco Sanudo, a relative of the Venetian Doge. Initially under the overlordship of the Latin emperor at Constantinople, the duchy later transferred its allegiance to Achaia (in 1261), and to Naples (in 1267), although Venice also laid claim to it. The Sanudo family was replaced in 1383 by the Lombard Crispi family, which retained its autonomy until after 1550, when the duchy was absorbed into the Ottoman state. The remaining islands were held at different times by Genoa, Venice, the Knights of St John and, eventually, the Turks. Rhodes played a particular role in the history of the Hospitallers’ opposition to the Ottomans from 1309 until its fall in 1523. The Knights were permitted under treaty to move their headquarters to Malta. In the northern Aegean, Lemnos remained Byzantine until 1453. Thereafter it came under the rule of the Gattilusi of Lesbos (independent until the Ottoman conquest in 1462). In 1460, it was awarded to Demetrios Palaiologos, formerly Lord of the Morea, along with the island of Thasos (which had fallen to the Ottomans in 1455). Lemnos was eventually occupied by Ottoman forces in 1479. Most of the Aegean islands had equally checkered histories - Naxos and Chios fell only in 1566, while Tenedos remained under the Venetians until 1715.

By 1371 the Ottoman forces had defeated the Serbs on the Maritza. In 1388 Bulgaria became a tributary state, and in 1389, following their victory (although the battle seems in fact to have been a draw, the Ottoman superiority in troops and resources gave them the advantage) at the battle of Kosovo, Ottoman forces were able to force the Serbs to accept tributary status. The Ottoman advance caused considerable anxiety in the west. A crusade was organised under the leadership of the Hungarian king, Sigismund, but in 1396 at the battle of Nikopolis his army was decisively defeated. The Byzantines, caught between the Ottomans and the western powers, attempted to play the different elements off against one another. One possible solution, the union of the two churches - with the inevitable subordination of Constantinople to Rome which this entailed - was espoused by some churchmen and part of the aristocracy. Monastic circles in particular, and much of the rural population, were bitterly hostile to such a compromise, to the extent even of arguing that subjection to the Turk was preferable. Hostility to the ‘Latins’ had become firmly entrenched in the minds of the majority of the orthodox population, both inside and outside the empire’s territories. Hesychasm, which represented an alternative to the worldly politics of the pro-westernists, thrived on this ground and further exploited the alienation between the two worlds. Neither party was able to assert itself effectively within the empire, with the result that the western powers remained on the whole apathetic to the plight of ‘the Greeks’.

In 1401 the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid began preparations for the siege of Constantinople. But the end was not yet reached. As the siege was under way, Mongol forces under Timur (Timur Lenk - Tamburlane) invaded Asia Minor, where, at the battle of Ankyra in 1402, the Ottomans were defeated and themselves forced to accept tributary status. In the Peloponnese, the Byzantines were able to use the opportunity to bring the remaining Latin princes under their authority. But the respite was of short duration. Timur’s death shortly afterwards brought with it the fragmentation of his empire and the revival, indeed strengthening, of Ottoman power. The Sultans consolidated their control in Anatolia, and set about expanding their control of the Balkans. The Emperor John VIII travelled widely in Europe attempting to muster support against the Islamic threat, even accepting ecclesiastical union with the western church at the Council of Florence in 1439, but this did little to hinder the inevitable. A last effort on the part of the emperors led to the western Crusade which ended in disaster at the battle of Varna in Bulgaria in 1444, and in 1453 Mehmet II set about the siege of Constantinople. After several weeks of the siege the Ottoman forces, equipped with heavy artillery, including cannon, were able to effect some serious breaches in the Theodosian walls. In spite of a valiant effort on the part of the imperial troops and their western allies, who were massively outnumbered, the walls were finally breached by the elite Janissary units on 29 May 1453. The last emperor, Constantine XI, died in the attack and his body was never found. Constantinople became the new Ottoman capital; the surviving Aegean isles were quickly absorbed by the Ottoman state; the despotate of Morea was conquered in 1460, and

Map 9.5 Decline and fall 1350-1453.

Trebizond, capital of the empire of the Grand Komnenoi, fell to a Turkish army the year after.

World History

World History