The Hundred Years’ War (1338-1453)

Edward III, born in 1312, reigned from 1327 to 1377. Initially under the tutelage of his mother and her lover, Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, Edward III bided his time. In 1330 he struck, having Mortimer arrested and executed, and his mother imprisoned for life. With this, young Edward re-opened the war with Scotland and then against France, having realized that the defeat of Scotland was not possible whilst it constantly received French aid. Edward III had serious grievances against the French. Their ships were a constant threat in the Channel and were doing their best to spoil England’s wool trade with Flanders. They were always supporting the Scots who stirred up troubles in the north. They held the Pope as a prisoner at Avignon and misused his influence on the English Catholic Church. They regularly broke their faith over English rights around the region of Bordeaux. Edward could not forget that all western France had belonged by right to his ancestor Henry II. Weak kings had lost most of the Plantagenet Empire, but a strong monarch could reconquer the lost territories in the same way. The English still retained, however, the extensive duchy of Guienne, for which the Kings of England did homage to the king of France. This arrangement produced constant difficulty, and the inevitable struggle between England and France was rendered the more serious by the claim made by Edward III that he was himself the rightful king of France. He based his pretensions upon the fact that his mother, Isabella, was the daughter of Philip the Fair. Philip, who died in 1314, had been followed by his three sons in succession, none of whom had left a male heir, so that the direct male line of the French Capetians was extinguished in 1328. The lawyers thereupon declared that it was a venerable law in France (the so-called Salic Frank Law, most probably created for the occasion) that no woman should succeed to the throne and transmit the crown to her son. Consequently Edward III

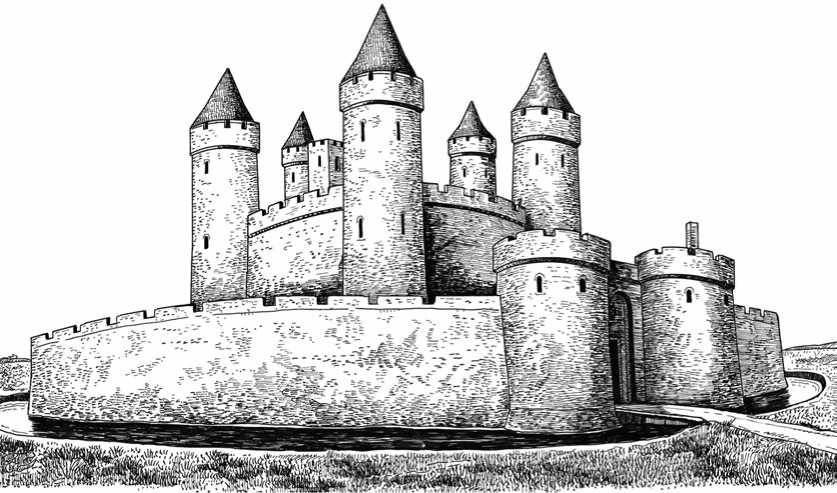

Above: Queenborough Castle once stood on the isle of Sheppey in Kent. Built by order of Edward III in order to defend the Swale estuary, as well as the narrow passage between Sheppey and mainland Kent, which was then one of the chief sea-routes to the Thames and London, the castle was named after Edward’s wife, Queen Philippa of Hainaut. The castle, designed by the architect John Box, featured a circular plan, which carried the principle of concentricity to its ultimate conclusion, and it would have been very difficult to storm. The outer bailey, hemmed with a moat, was concentric with the keep, but walled passages on each side connected the keep with the outer countryside and could still be defended even if the outer bailey was captured. The inner bailey featured six circular towers projecting from an inner curtain wall, and ranged around a circular courtyard. Queenborough was also one of the first English castles to be designed in order to withstand siege artillery fire and mount defensive cannons. Its novel design for its time anticipated the centrally planned artillery coastal forts of Henry VIII by nearly 200years. For a while, Queenborough was a favored royal residence, but its importance declined with the decay of the River Swale as shipping route. The castle was declared obsolete in 1650 and demolished under the Commonwealth soon after. Today only a few mounds and Edward’s church remain.

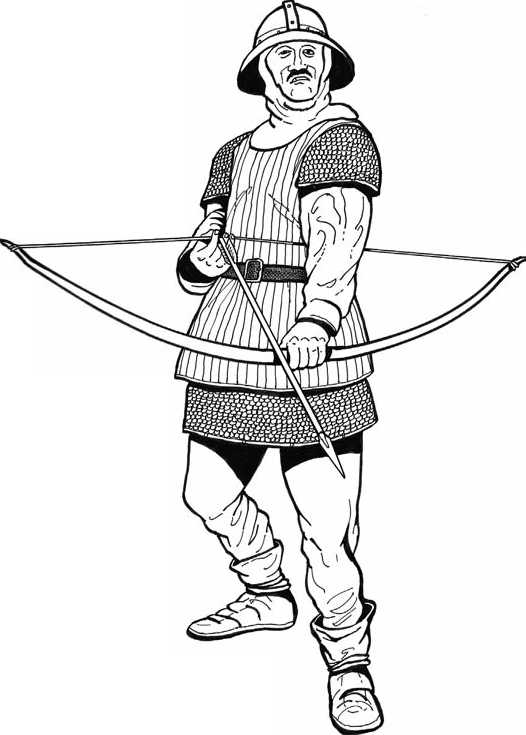

Opposite top: English archer. The English longbow (of Welsh origin) was a powerful weapon about 6 feet 6 inches (2.0 m) long used by the English, Scots and Welsh, both for hunting and as a weapon of war. The longbow proved its effectiveness against the French, particularly at the start of the Hundred Years’ War in the battles of Crecy (1346) and Poitiers (1356), and most famously at the Battle of Agincourt (1415). The range of the bow is estimated to be 180 to 249 yards (165 to 228 m). Most of the longer-range shooting was not marksmanship, but rather archers would aim at an area and shoot a rain of arrows hitting indiscriminately anyone in the target zone, a decidedly unchivalrous but highly effective means of combat. The use of the longbow terminated the ascendancy in war of the mailed horseman of the feudal regime.

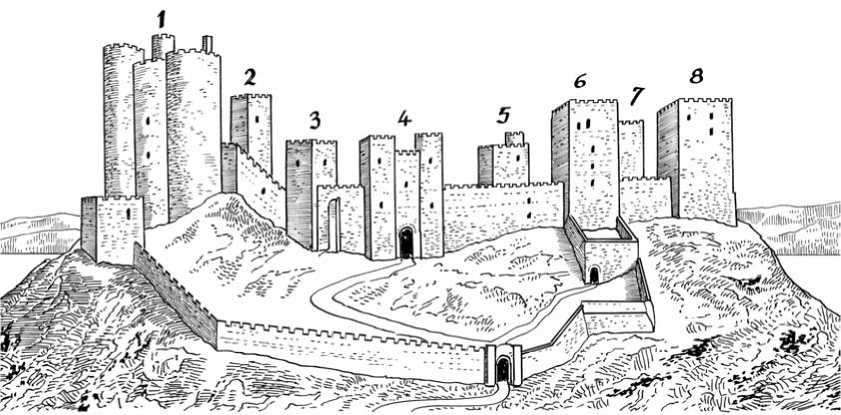

Bottom: The now ruined castle of Pontefract is located some 13 miles from Leeds in West Yorkshire. The history of Pontefract Castle begins with the Norman conquest as an earth and timber fortress built by Ilbert de Lacy in the 1080s. The castle was rebuilt in stone in the 12th century and other buildings were added as time went on. As the castle was strengthened so was the power of the de Lacy family. Following very successful marriages they became Earls of Lincoln and eventually estates were transferred to the powerful house of Lancaster. The castle played an important role in English medieval history.

Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, was tried for treason at Pontefract Castle and executed on the hill adjacent to nearby St. John’s Priory. There were other important prisoners—James I of Scotland and the French Charles of Valois and Duc d’Orleans (captured at the battle of Agincourt in October 1415 and held as a hostage for 24 years). But the most infamous event at Pontefract Castle was the incarceration and murder of King Richard II, immortalized in Shakespeare’s play. The castle has been a ruin since 1644. Today, although a scheduled ancient monument in the care of Wakefield Council, it is still the property of Her Majesty the Queen as part of the Duchy of Lancaster.

The illustration, based on a painting by Alexander Keirincx, shows how the castle might have looked before the English Civil War destruction. It included 1: Multilobed keep on motte (presenting similarities with Clifford Tower in York, and Etampes in France); 2: Piper Tower; 3: Gascoigne Tower; 4: Gate house; 5: Swillington Tower; 6: Constable Tower; 7: Queen’s Tower; and 8: King’s Tower.

Appeared to be definitely excluded, and Philip VI of Valois, a nephew of Philip the Fair, became king of France. At first Edward III appeared to recognize the propriety of this settlement and did qualified homage to Philip VI for Guienne. But when it became apparent later that Philip was encroaching upon Edward’s prerogatives in Guienne, he publicly declared himself the rightful king of France. So started the so-called Hundred Years’ War, a long but frequently interrupted series of conflicts between England and France. The struggle was carried on intermittently during the reigns of five English kings. From 1338 to 1360 the advantage lay with England owing to resounding victories at Sluys (1340), Crecy (1346), and Poitiers (1356), culminating in the Treaty of Bretigny (1360). In the 1370s the English lost command of the sea, at any rate from time to time, and England’s coasts were exposed to attack by the French and their Spanish allies (e. g., Isle of Wight, Rye and Winchelsea). This was the first of the periodic invasion scares which, right up to the early 1940s, were to leave numerous fortification works on the southern coastline.

A deadly bubonic plague, known as the Black Death, appeared in Europe early in 1348, and spread over England one year later. It is impossible to tell what proportion of the population perished, but a careful estimate shows that in England toward one third of the population died.

With the death of the Black Prince in 1376, and the accession of Richard II (1377-1399), English fortunes reached their lowest ebb. Richard II also had to face in 1381 an important revolt of the peasants in Kent and Essex. There was a growing discontent among the English agricultural classes, which may be ascribed partly to the results of the great pestilence and partly to the new taxes, which were levied in order to prolong the disastrous, pointless and hopeless war with France, then being conducted by incapable soldiers and highly unpopular ministers. The reign of Henry IV (1399-1413) began a period of improvement, which was continued by Henry V (1413-1422), whose reign was marked by a victory at Agincourt (1415) and the Treaty of Troyes (1420). The accession of the nine-month-old Henry VI (1422-1461), and the appearance of Joan of Arc in 1428, saw the tide turn in favor of the French. By 1453, the Hundred Years’ War was over, and although England still retained the port of Calais in northern France, the great question of whether she should extend her sway upon France was finally settled.

The Wars of the Roses (1455-1485)

The close of the Hundred Years’ War was followed in England by the so-called Wars of the Roses, between the rival houses of Lancaster and York, which were struggling for the crown. The badge of the house of Lancaster, to which Henry VI belonged, was a red rose, and that of the duke of York, who proposed to push him off his throne, was a white one. Each party was supported by a group of the wealthy and powerful nobles—earls, dukes and barons whose rivalries, conspiracies, treasons, murders, and executions fill the annals of England during the period. The miserable Wars of the Roses lasted from 1455, when the duke of York set seriously to work to displace the weak-minded Lancastrian king, Henry VI, until the accession of Henry VII of the house of Tudor thirty years later. After several battles the Yorkist leader, Edward IV, assumed the crown in 1461 and was recognized by Parliament, which declared Henry VI and the two preceding Lancastrian kings usurpers. Edward IV was a vigorous monarch and maintained his own until his death in 1483. Edward IV’s son, Edward V, was only a boy, so government fell into the hands of the young king’s uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester. The temptation to make himself king was too great to be resisted, and Gloucester soon seized the crown, becoming King Richard III. Both the sons of Edward IV were killed in the Tower of London, with the knowledge of their uncle, it is commonly believed. A new aspirant to the throne organized a conspiracy. Richard III was defeated and slain in the battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, and the crown was placed upon the head of the first Tudor king, Henry VII. The latter had no particular right to it, although he was descended from Edward III through his mother. He hastened to procure the recognition of Parliament and married Edward IV’s daughter, thus blending the red and white roses in the Tudor badge, and bringing an end to this bloody and pointless dynastic struggle.

Gunpowder and Artillery

During the Hundred Years’ War appeared a small professional group of people who enjoyed no social status whatever, and who were barely accorded the humble status of soldiers: the artillerymen. The earliest instruction for using black powder was given by the English friar Roger Bacon in the 1240s but it was not until the battle of Crecy in 1346 that firearms seem to have made a first and timid appearance within the English armed forces. The origins of gunpowder are hidden away and who made the first firearm using black powder as propellent remains equally unknown. By the end of the Hundred Years’ War, in the 1450s, cannons had been significantly improved, and they slowly but surely fundamentally changed the art of warfare. Gradually, the new weapons became more than a noisy and smoky curiosity, but their introduction did not bring a revolution in warfare overnight. A spectacular use of artillery occurred during the siege and fall of Constantinople in April and May 1453, when the Turks used enormous cannons that made breaches in the city walls. Artillery became established as an important and decisive weapon during King Charles VIII of France’s Italian campaign in 1494. The introduction of firearms was thus a long, slow process that, however, could not be stopped. Gradually, as the new weapons had proved their worth on the battlefield and more particularly in siege warfare, artillery came to form a part of the military equipment of the armies of Western Europe. Carpenters had been the traditional engineers, siege experts and makers of war-machines, but now with the coming of gunpowder they began to yield place to the smiths. By the end of the 15th century, the more early exotic products had disappeared and the two fire weapons, which between them were to dominate the conduct of war, were emerging in clearly recognizable form: the crew-served cannon and the portable individual handgun. Gunpowder also allowed a new and more decisive employ of the

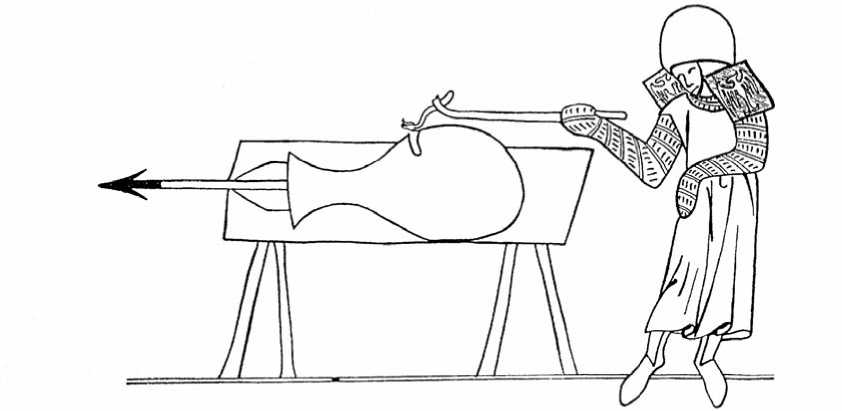

Above: This illustration, based on a picture published in a book by Walter of Milimete in c. 1327, shows the first known representation of a gun. The barrel resembles a vase placed on a curious and rudimentary mounting which looks like a table-like surface. The gun is being ignited by a knight holding a taper to a hole in the base of the breech. The projectile is a kind of dart.

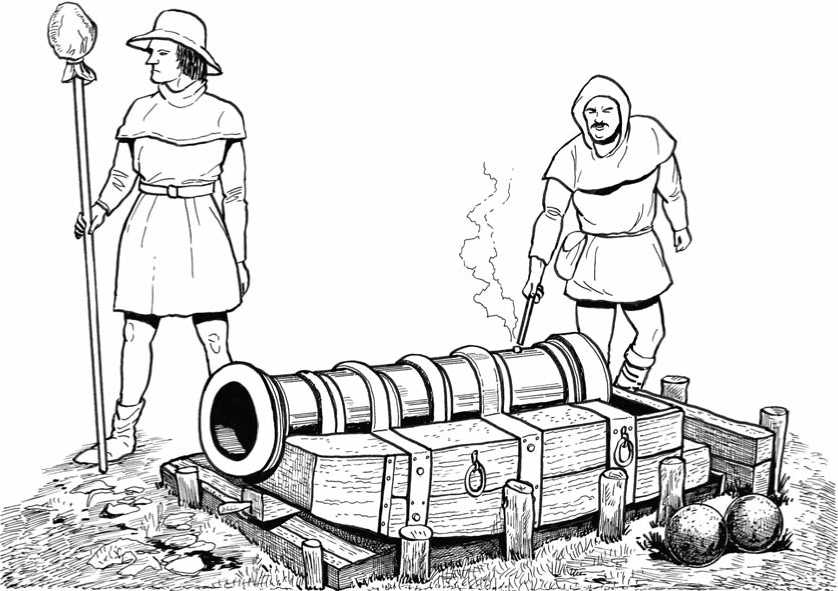

Below: The bombard was a ponderous early gun made of wrought-iron bars bound with hoops. Mounted on a rudimentary wooden frame, it was predominantly a siege weapon that shot stone balls with little accuracy, a limited range and a poor rate of fire.

Left: Mercenary billman. The English Wars of the Roses, with their constant shifting of loyalties, made the employment of mercenaries from the Continent an attractive proposition. German, Swiss, Burgundian, Flemish and French mercenaries were hired at one time or another during the struggle for England’s throne. For example, by 1450 the Duke of Buckingham had a private army of2,000 men. The illustrated man wears a salet helmet and a soft armored quilted jerkin. His weapons include a guisarme (bill), a “kidney” dagger, and a sword.

Right: Early small caliber arms (called fire stick, culverine, bombardelli, clopi, scopet, or petronel) appeared in the 1400s. They were awkward, slow and clumsy to use, actually cannons in reduction, comprising a simple iron tube eventually fixed to a wooden handle.

Mine in siege warfare methods. Henceforth, one of the standard techniques of breaching a fortress was to dig a tunnel under its wall, place kegs of gunpowder, and detonate them to let the explosion blast away the solid foundations. Gunpowder — packed in the form of an explosive charge known as a petard — could also be used to destroy barricades, obstacles, walls, posterns, doors and portals in gatehouses. Another significant development was the introduction in the early 16th century of a short and massive gun, called a mortar, which fired its projectiles up into the air in a high trajectory (called plunging fire) so as to lob and drop deadly charges over walls and other defenses, which the flat trajectory of the cannon could not reach. Improvement of gunpowder and artillery technology had political consequences. The development of really efficient cannons gave central authorities in all states of Western Europe an opportunity to establish their power over feudal lords, who tended to lack the resources to acquire them or to build fortresses capable of withstanding artillery.

World History

World History