The arquebus

Variously named ‘hachebuchsen’, ‘hag-but’, ‘hagbush’, ‘harquebus’, etc, all meaning hook-gun. The usual explanation of this is that the ‘hook’ was an attachment beneath the barrel, hooked over a wall or branch to take the recoil, but it seems more likely that it came from the hooked shape of butt or ‘serpentine’, since these developments were contemporary with the name, while the hook beneath was present on many pre-arquebus guns and absent on the majority of arquebusses.

The chief infantry firearm of the 16th Century, used by mounted men too, it remained in use, for skirmishers and cavalry, into the 17th Century.

The arquebus developed from the clumsy handguns of the 15th Century, probably in Germany, through the development of a simple lock mechanism around the end of the century, by which a pivoted ‘serpentine’ held the glowing ‘match’ (cord soaked in a saltpetre solution), and dropped it onto the pan, hopefully firing the gun, when some type of trigger was pressed. This cheap and simple ‘matchlock’ mechanism was used for nearly all infantry weapons throughout the period, though in fact guns with no lock at all still remained in use in the early 16th Century.

The other critical development was a proper butt; in the 16th Century often held against the chest or cheek (ouch!), later against the shoulder.

In the early 16th Century, arquebusses were of no particular size, the largest being almost light field guns (a German

German infantry shield of the late 15th Century bearing the arms of Wimpfen (Tower of London).

Doppelte-Doppel-Haken was seven feet long, weighed 50 pounds, and fired a six ounce ball to about 500 yards). Such guns needed two men, and were sometimes mounted on carts or walls. There was an unbroken range down to little half-hakes firing a ball of 20 to the pound. The most common types seem to have been about three foot six inches long, firing a 1V2 ounce ball, and weighing around ten pounds.

From the 1540s, there seems to have been growing standardisation on two types: the heavier one was the musket (see below), the lighter, what was called in England a ‘Caliver’ (from calibre, which, originally in France, had become more or less standardised). Such weapons were around four feet long, 12 pounds in weight, and had a calibre of 0.5 to 0.75 inches, firing lead balls of ten to 16 to the pound.

Maximum range of the best Italian arquebusses, carefully loaded, was said to be about 400 yards, but effective range in battle, and certainly accurate range, would be much less. A target range at Augsburg in 1508 was 226 yards long, and English caliver-men of Elizabeth’s reign were supposed to be able to hit the mark at 200 to 300 paces, so it is reasonable to suppose that arquebusses would be fairly effective up to 150 yards or so, at least against large targets.

Loading was a major problem. 17th Century musket drill included no less than 48 movements, but this gives a somewhat exaggerated idea of its complexity, being intended for training. In battle, ‘Make ready', ‘Present’, and ‘Fire’ were the only commands necessary. However, it is probably true that loading the arquebus required two hands, the musket, three! The need to

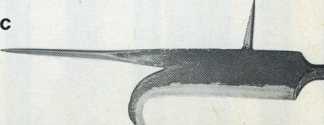

A Eastern European Berdische poleaxes, b 16th Century Glaives. cA 16th Century Bill (Tower of London).

Remove and hold in one hand about two feet of match, lighted at both ends, while messing about with loose gunpowder, must have made the whole procedure quite exciting. Early in Elizabeth’s reign, 12 rounds an hour was apparently considered fair going, and even by the late 16th Century English caliver men only managed 40 shots an hour — and at that they claimed to fire twice as fast as musketeers!

One factor in increasing the rate of fire was the development of the bandolier, from which dangled, usually, 12 wooden cases (nine at the front, three at the back), each with powder for one shot; bullets were carried separately in a bag and priming powder in a flask or horn. Early bandoliers were sometimes worn round the neck, later over the left shoulder. Paper cartridges would have helped still more, but were certainly not used by infantry before the 30 Years’ War, if then, although invented in the 16th Century.

The musket

’Musket’ was simply the name applied to the heavier and longer-barrelled types of arquebus from about the 1540s onwards; like them it required a forked rest to support it in action, and the early Spanish muskets had a crew of two. The Spanish were the first to use it on any scale; their muskets differed from English, German and French ones in having a straight rather than a curved stock (Sir Roger Williams said that the Spanish type was better for taking recoil).

Even in Spanish service, however, the 16th Century pikes (Tower of London).

Musket was greatly outnumbered by arquebusses for a long time — in the 1580s the Duke of Alva’s armies in the Netherlands had only one musketeer to every seven arquebusiers, and others were slow to take-up such weapons at all (the French army did not use them till 1573). By the early 17th Century, muskets were practically universal, though the Spanish retained a good many arquebusiers and were said to have profited, at Nieuport, from their greater handiness. Later reductions in the weight and size of muskets would remove any such advantage.

It is difficult to give very precise details of muskets, particularly as there were ‘double’ and ‘half’ muskets in use as well, but a length of about six feet, weight of 16 to 20 pounds, and bullets of about two ounces, would seem to be fairly typical for the 16th Century; in the 17th Century there was a strong trend toward reduction in size and weight, probably initiated earlier by the Dutch. English Civil War muskets, which were of ‘Dutch pattern’, fired balls of 12 or 14 to the pound, and Gustavus Adolphus reduced the weight of Swedish ones to 11 or 12 pounds. However, muskets retained the long barrel which gave them greater velocity and range than the lighter types of arquebus, and the use of a rest remained generally necessary to about the end of our period.

A musket of the late 16th Century could kill a man in ‘shot-proof’ armour at ‘ten score paces’, a ‘common armed’ man at 20 score, and an unarmoured man at 30 score.

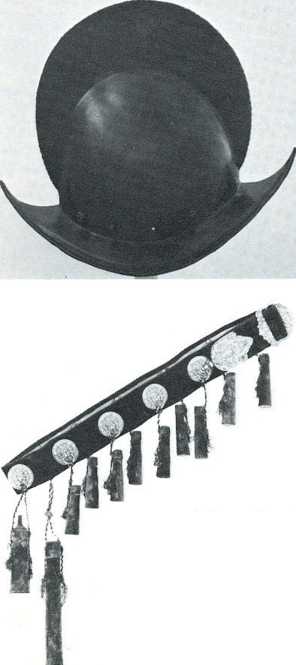

16th Century morion (Tower of London).

A Saxon Guard bandolier of the early 17th Century (Tower of London).

And there are many stories of muskets killing at up to 500 yards. They certainly had much greater range than earlier weapons, and (perhaps more important, as one would not expect to hit anything much over 200 yards or so) much higher armour-piercing capability, which was probably the main cause of the decline of armour which took place in the late 16th and 17th Century.

The matchlock had many disadvantages, apart from loading problems; wind blew the match out or the powder from the pan, rain was equally bad; the glowing match gave away night movements (though this had the compensation that a row of matches hung on trees made a good dummy unit for covering night withdrawals) and it could even ignite one of the cartouches on the bandolier, with unhappy results. Some of these troubles were avoided by the snaphance, or early flintlock (like wheel-locks, often referred to as ’firelocks’) which appeared in the 16th Century, and offered considerably better rates of fire than matchlocks. Extra expense seems to have confined them to bodyguards, mounted troops and men detailed to guard artillery trains (where burning matches were not wanted near powder barrels), though the Dutch in particular may have made wider use of them.

Both match - and flint-locks suffered from the high-sulphur powder of the period, which clogged the bores and often caused bursting, and produced even more smoke than in Napoleonic days; ‘getting the wind of the enemy’ so that their own smoke blew back in their eyes, was a recommended opening manoeuvre.

Rifling was also introduced in the 16th Century, and offered much higher accuracy (one school of thought attributed this to the fact that devils could not cling to a spinning ball), at the cost of even slower loading and, possibly, reduced range. The number of rifled guns in the inventories of German arsenals of the 16th Century makes it seem as though they were probably intended for military use, and some were certainly used by ‘snipers’ during the English Civil War.

World History

World History