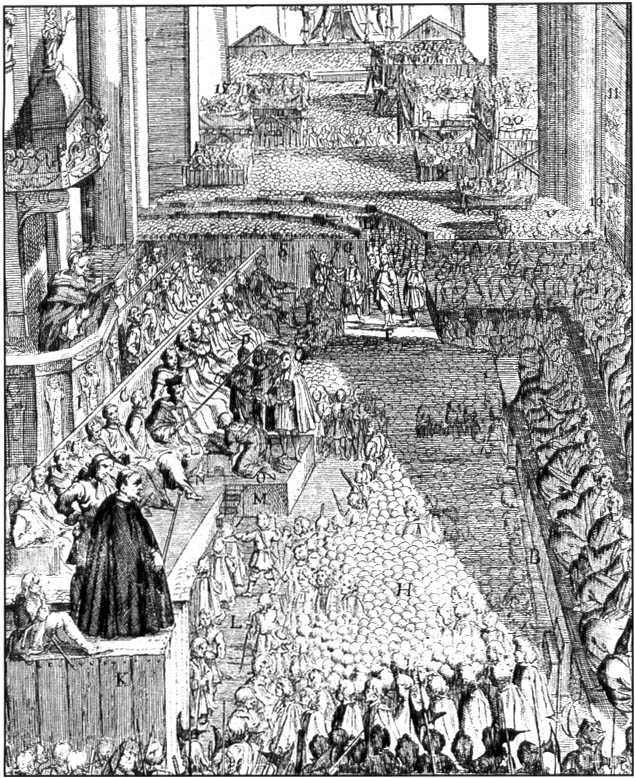

The Inquisition proceeded in secrecy until it had either gotten a repentance from the person it was investigating or sufficient evidence to condemn the suspect.

Traditionally bishops had been charged with the spiritual correction of the laity, including dealing with heresy. In the 1230s, the papacy replaced the bishops with tribunals of judges. These tribunals, known as the Inquisition, were made up of well-educated churchmen who had taken religious vows (often in the Dominican order). They were given

Sweeping powers to question suspected heretics and witnesses. The Inquisition, which did not allow suspects to confront witnesses or obtain legal counsel, accepted the testimony of two witnesses as sufficient evidence for conviction. The inquisitors often used torture as a way of extracting a confession. Their goal was to save the souls of those who had been led astray

By heresy. Therefore they sought confessions, so that they could bring heretics back into the fold of the Church where the salvation of their souls could be assured. Those who confessed were given penances or prison terms. Only when heretics refused to recant their beliefs were they burned at the stake or otherwise executed.

Enough, the mobs had been so rough in their jubilation that he had died as they flocked around him to touch the true lance.

The Lateran council called for the exclusion of priests from ordeals and judicial combats. This policy forced monarchs to change the way they established guilt or innocence in criminal cases. No one was satisfied with ordeal, because the horror of it simply forced the accused and the accusers to reach an agreement. England had a tradition of using juries to settle land disputes and to decide if there was adequate evidence in a case to indict a person for a crime. Indictment meant that the known evidence strongly suggested that the person might be guilty and that he should therefore be tried in the king’s court. The indictment jury eventually was named the grand (large) jury. To replace ordeals and combat, England created another jury, the petty {petit or small) jury, which rendered the verdict at the conclusion of a trial.

On the continent, a different model was selected. Instead of a jury, a board of magistrates or judges questioned the accusers and then, separately, questioned the accused. The two sides did not confront each other, which prevented the possibility of intimidation on either side. Thejustices then rendered a decision. Guilt in either system resulted in punishment by hanging. Fortunately, both systems were lenient, and only about a quarter of the accused were hanged.

The Church itself was having problems with a large minority of laity who held beliefs contrary to those of the official doctrine. In the urban centers of southern Europe, the population began to question the growing power of the clergy and the

Wealth of the Church. Several heresies disturbed Innocent and the Church, but the most alarming were the beliefs of the Cathari (the pure), also known as the Albigensians, a name derived from the town of Albi in southern France around which their movement was centered.

The Albigensians offered a coherent, distorted, and appealing alternative to the theology of the Church. Their theology might have had its origins in the Zoroas-trian dualistic religion of Persia. Both recognized two gods: a god of good who represented the spirit and a god of evil who represented the world of matter or material life. Because the Old Testament contained the story of the creation of the material world, in their view it portrayed the god of evil. The New Testament, they believed, portrayed the god of good, for it dealt with salvation, souls, and resurrection. Because spirit was better than flesh, the Albigensians urged abstinence from worldly living, animal meat, and sex. In fact, only a few Albigensians, thepeifecti or the perfect ones, were able to follow this severe regime. When Albigensians died, they requested one of the perfecti to be at their bedside to speed salvation.

By the beginning of the 13th century the Albigensians were attracting a large following, and Innocent III became alarmed. With no immediate weapon to combat them, he preached that a crasade should be undertaken against them in 1208. He promised the successful leader of the crusade the right to take over the Albigensians’ property in southern France. The crusade was brutal, but not until 1229 was the heresy under control. Many

Albigensians were killed, and some returned to Christianity, but a determined group of believers practiced their religion secretly. To root out these secret groups of Albigensians, the Church resorted to the Inquisition, a tribunal for the discovery and punishment of heretics.

The Albigensian Crusade was not the first that Innocent had launched. In 1202 he persuaded some European noblemen to undertake the Fourth Crusade to liberate the Holy Land from the Turks. The crusaders contracted with the Venetians to take them there by boat, but when they were unable to pay, the Venetians suggested that, as part of their payment, they could recapture a trading port that had been claimed by the Hungarian king. When Innocent learned of this attack on a Christian king, he excommunicated the crusaders. Undaunted, they decided to proceed to Constantinople, where in 1204 they attacked and looted the capital and drove out the emperor. Their domination of the city lasted only 50 years, but those who participated in the crusade returned to Europe with immense wealth in gold and gems, as well as many religious relics.

Church councils and crusades were not the most effective way to confront and counter dissent. Instead, new religious orders sprang up to provide the laity with spiritual and intellectual guidance. Dominic (1170-1221), a Spaniard by birth, received an excellent education in the Hebrew/ Arabic/Christian environment ofhis native country. In his mid-30s he traveled to Rome, where he met Innocent III. Innocent, worried about the Albigensian crisis, asked him to preach against the heretics in

Relics of saints, including their bones and clothing, played an important part in religious worship during the Middle Ages. People felt that saints could intervene to help cure them of diseases or ease other distress. The relics were housed in rich reliquaries and became part of a church’s treasuiy. Pieces of the cross on which Jesus was executed, contained in this reliquary, were especially important.

World History

World History![Stalingrad: The Most Vicious Battle of the War [History of the Second World War 38]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432581864_1425486471_part-38.jpeg)