In Chapters 4 through 6, we saw how alternatives to classical Hollywood cinema arose in the form of stylistic movements. Other alternatives to mainstream Hollywood fare also appeared. In the United States, such alternatives have usually been specialty films aimed at specific audiences. During the silent era, a small circuit of theaters for African American audiences developed, along with a number of regional producers making films with all-black casts.

In 1915, the release of Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation led to many protests and boycotts on the part of African Americans. Some envisioned the creation of black-controlled production firms that could provide an alternative perspective on race relations. A few sporadic attempts at production were initiated during the latter half of the 1910s, but the results were usually short films that were relegated to a minor role on programs. They either showed positive images of black heroism during World War I or perpetuated traditional black comic stereotypes.

During the 1920s, black roles in mainstream Hollywood films were minor and still based on stereotypes. African Americans appeared as servants, wastrels, comic children, and the like. Black actors seldom found regular work and had to fill in with other jobs, usually menial, to survive.

As moviegoers, African Americans had little choice but to attend theaters that showed films designed for white audiences. Most theaters in the United States were segregated. In the South, laws required that exhibitors separate their white and black patrons. In the North, despite civil rights statutes in many localities, the practice was for the races to sit in separate parts of auditoriums. Some theaters, usually owned by whites, were in black neighborhoods and catered to local viewers. In such theaters, any films with black-oriented subject matter proved popular.

There were even a small number of films produced specifically for African American audiences. These used all-black casts, even though the directors and other filmmakers were usually white. The most prominent company of this kind in the 1920s was the Colored Players, which made several films, including two particularly significant ones. The Scar of Shame (1929?, Frank Perugini) dealt with the effects of environment and upbringing on black people’s aspirations. The hero, a struggling composer, strives to live a respect-a ble middle-class existence; he is “a credit to his race,”

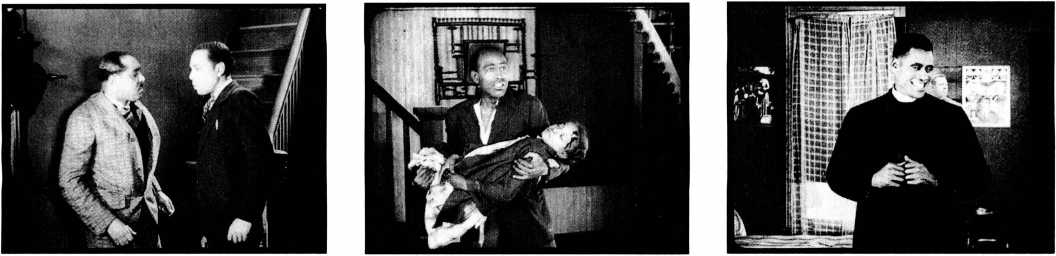

7.53 The conservatively dressed hero of Scar of Shame confronts the villainous gambler, marked by his sporty checked suit.

7.54 The hero of Ten Nights in a Barroom holds his fatally wounded daughter.

7.55 Paul Robeson as the villain in Body and Soul.

Despite the attempts of sordid characters to corrupt him (7.53).

The Colored Players also made a less preachy film that has survived, Ten Nights in a Barroom (1926, Charles S. Gilpin), an adaptation of a classic stage melodrama that had traditionally been played by white casts. Its complex flashback structure tells the story of a drunkard who reforms when he accidentally contributes to the death of his daughter in a barroom brawl (7.54). Despite its low budget, Ten Nights in a Barroom was skillfully lit and edited in the classical style.

In rare cases, black filmmakers were able to work behind the camera. Oscar Micheaux was for several decades the most successful African American producer-director. He began as a homesteader in South Dakota, where he wrote novels and sold them door to door to his white neighbors. He used the same method to sell stock to adapt his writings into films, creating the Micheaux Book and Film Company in 1918. Over the next decade, he made thirty films, concentrating on such black-related topics as lynching, the Ku Klux Klan, and interracial marriage.

The energetic and determined Micheaux worked quickly with low budgets, and his films have a rough, disjunctive style that boldly depicts black concerns on the screen. Body and Soul (1924) explores the issue of the religious exploitation of poor blacks. Paul Robeson, one of the most successful black actors and singers of the century, plays a false preacher who extorts money and seduces women (7.55). Micheaux went bankrupt in the late 1920s and had to resort to white financing in the sound era. Nevertheless, he continued to average a film a year up to 1940 and made one more in 1948. Although much of his work is lost, Micheaux demonstrated that a black director could make films for black audiences.

The opportunities for African Americans would improve somewhat during the sound era. Talented black entertainers were in greater demand in musicals, and major studios experimented with all-black casts. As we shall see in Chapter 9, one of the most important early sound films, King Vidor’s Hallelujah!, attempted to explore African American culture (p. 200).

World History

World History