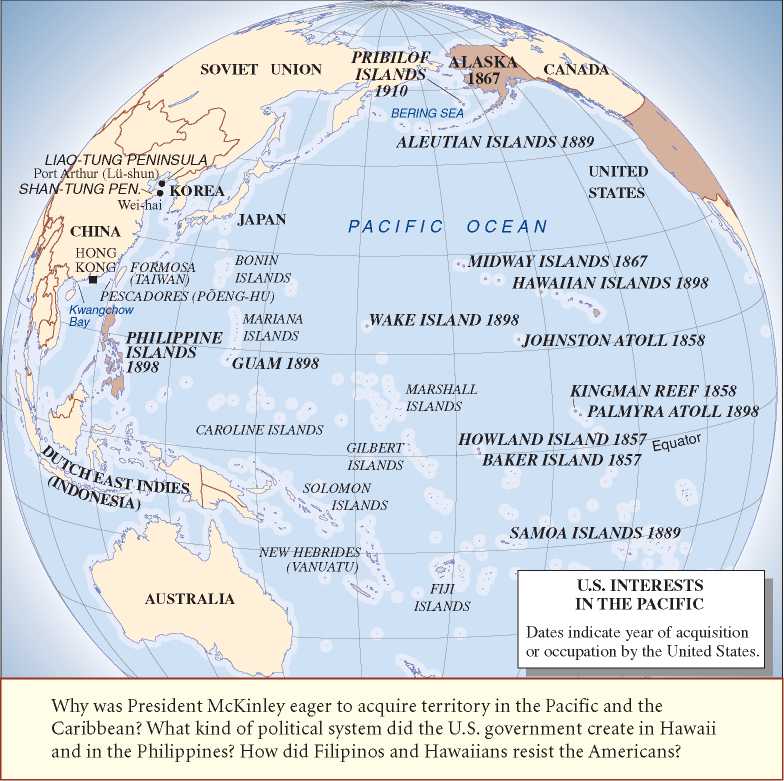

What motivated America’s “new imperialism”?

What was the role of religion as a motive for American territorial expansion?

What were the causes of the War of 1898?

What did America gain from the War of 1898?

What were the main achievements of President Roosevelt’s foreign policy?

= hroughout the nineteenth century, Americans displayed

What one senator called “only a languid interest” in foreign, affairs. The overriding priorities were at home: industrial

Development, western settlement, and domestic politics. Foreign relations simply were not important to the vast majority of Americans. After the Civil War an isolationist mood swept across the United States as the country basked in its geographic advantages: wide oceans as buffers, the powerful British navy situated between America and the powers of Europe, and militarily weak neighbors in the Western Hemisphere.

Yet the notion of the United States having been ordained by God to expand its territory and its democratic values remained alive in the decades after the Civil War. Several prominent political and business leaders argued that sustaining rapid industrial development required the acquisition—or conquest—of foreign territories in order to gain easier access to vital raw materials. In addition, as their exports grew, American manufacturers and commercial farmers became increasingly intertwined in the world economy. This growing involvement in international commerce, in turn, required an expanded naval force to protect the shipping lanes from hostile action. And a modern steam-powered navy needed bases where its ships could replenish their supplies of coal and water.

For these and other reasons, the United States during the last quarter of the nineteenth century expanded its military presence and territorial possessions beyond the Western Hemisphere. Its motives for doing so were a mixture of moral and religious idealism (spreading the benefits of democratic capitalism and Christianity to “backward peoples”), popular assumptions of racial superiority, and naked greed. Such confusion over ideals and purposes ensured that the results of America’s imperialist adventures would be decidedly mixed. Within the span of a few months in 1898 the United States, which was born in a revolution against British colonial rule, would itself become an imperial ruler whose expanding overseas commitments would have unforeseen—and tragic—consequences.

Toward the New Imperialism

By the late nineteenth century, the major European nations had unleashed a new surge of imperialism in Africa and Asia, where they had seized territory, established colonies, and promoted economic exploitation, racial superiority, and Christian evangelism. Writing in 1902, the British economist J. A. Hobson declared that imperialism was “the most powerful factor in the current politics of the Western world.”

Imperialism in a global context Western imperialism and industrial growth generated a quest for new markets, new sources of raw materials, and new opportunities for investment. The result was a widespread process of aggressive imperial expansion into Africa and Asia. Beginning in the 1880s, the British, French, Belgians, Italians, Dutch, Spanish, and Germans used military force and political guile to conquer those continents. Each of the imperial nations, including the United States, dispatched missionaries to convert conquered peoples to Christianity. By 1900, some 18,000 missionaries were scattered around the world.

AMERICAN imperialists As the European nations expanded their control over much of the rest of the world, the United States also began to acquire new territories. A small yet vocal and influential group of public officials aggressively promoted the idea of acquiring overseas possessions. The expansionists included Senators Albert J. Beveridge of Indiana and

Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, as well as Theodore Roosevelt and naval captain Alfred Thayer Mahan.

During the 1880s, Captain Mahan had become a leading advocate of sea power and Western imperialism. In 1890 he published The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783, in which he argued that national greatness flowed from maritime power. Mahan insisted that modern economic development required a powerful navy, a strong merchant marine, foreign commerce, colonies, and naval bases. A self-described imperialist, Mahan championed America’s “destiny” to control the Caribbean, build an isthmian canal to connect the Pacific and the Caribbean, and spread Western civilization in the Pacific. His ideas were widely circulated in popular journals and within political and military circles. Theodore Roosevelt, the war-loving assistant secretary of the navy, ordered a copy of Mahan’s book for every American warship. Yet even before Mahan’s writings became influential, a gradual expansion of the navy had begun. In 1880 the nation had fewer than a hundred seagoing vessels, many of them rusting or rotting at the docks. By 1896, eleven powerful new steel battleships had been built or authorized.

IMPERIALIST THEORY Claims of racial superiority bolstered the new imperialist spirit. Spokesmen in each industrial nation, including the United States, used the arguments of social Darwinism to justify economic exploitation and territorial conquest. Among nations as among individuals, expansionists claimed, the fittest survive and prevail. John Fiske, a historian and popular lecturer on Darwinism, stressed in 1885 the superior character of “Anglo-Saxon” institutions and peoples. The English-speaking “race,” he argued, was destined to dominate the globe and transform the institutions, traditions, language—even the blood—of the world’s peoples. Josiah Strong added the sanction of religion to theories of racial and national superiority. In his best-selling book Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis (1885), Strong asserted that the “Anglo-Saxon” embodied two great ideas: civil liberty and “a pure spiritual Christianity.” The Anglo-Saxon was “divinely commissioned to be, in a peculiar sense, his brother’s keeper.”

Expansion in the Pacific

For Josiah Strong and other expansionists, Asia offered an especially alluring target for American imperialism. In 1866, the secretary of state, William H. Seward, had predicted that the United States must inevitably exercise commercial domination “on the Pacific Ocean, and its islands and continents.” Eager for American manufacturers to exploit Asian markets, Seward believed the United States first had to remove all foreign interests from the northern Pacific coast and gain access to that region’s valuable ports. To that end, he cast covetous eyes on the British colony of British Columbia, sandwiched between Russian America (Alaska) and the Washington Territory.

Late in 1866, while encouraging British Columbians to consider making their colony a U. S. territory, Seward learned of Russia’s desire to sell Alaska. He leaped at the opportunity, in part because its acquisition might influence British Columbia to join the union. In 1867, the United States bought Alaska for $7.2 million, thus removing Russia, the most recent colonial power, from North America. Critics scoffed at “Seward’s folly” of buying the Alaskan “icebox,” but it proved to be the biggest bargain since the Louisiana Purchase.

HAWAII The Americans who were promoting expanded commercial relations with Asia coveted the Hawaiian islands. The islands, a united kingdom since 1795, had a sizable population of American missionaries and sugar. In 1875, the kingdom had signed a reciprocal trade agreement with the American government, according to which Hawaiian sugar would enter the United States duty-free and Hawaii promised that none of its territory would be leased or granted to a third power. This agreement resulted in a boom in sugar production, and American planters in Hawaii soon formed an economic elite that built its fortunes on cheap immigrant labor, mainly Chinese and Japanese. By the 1890s, the native Hawaiian population had been reduced to a minority by smallpox and other foreign diseases, and Asians quickly became the most numerous group.

In 1885, President Grover Cleveland called the Hawaiian islands “the stepping-stone to the growing trade of the Pacific.” Two years later, Americans in Hawaii forced the king to convert the monarchy to a constitutional government, which they dominated. In 1890, however, the McKinley Tariff destroyed Hawaii’s favored position in the sugar trade by putting the sugar of all countries on the duty-free list and granting growers in the continental United States a 2$ subsidy per pound of sugar. This change led to an economic crisis in Hawaii and brought political turmoil as well.

In 1891, when Liliuokalani, the king’s sister, ascended the throne, she tried to eliminate the political power exercised by American planters. Two years later Hawaii’s white population revolted and seized power. The U. S. ambassador brought in marines to support the coup. As he cheerfully reported to the secretary of state, “The Hawaiian pear is now fully ripe, and

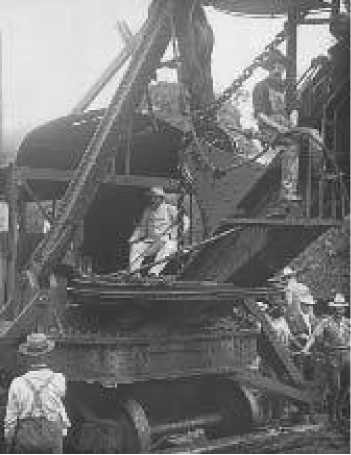

Cutting sugar cane

Heightened demand for cheap labor in the sugar cane fields dramatically affected the demographic and political conditions of the Hawaiian islands.

This is the golden hour for the United States to pluck it.” Within a month a committee of the new government in Hawaii turned up in Washington, D. C. with a treaty calling for the island nation to be annexed to the United States.

President Cleveland then sent a special commissioner to investigate the situation in Hawaii. The commissioner removed the marines and reported that the Americans in Hawaii had acted improperly. Most Hawaiians opposed annexation to the United States, the commissioner found. He concluded that the revolution had been engineered mainly by the American planters hoping to take advantage of the subsidy for sugar grown in the United States. Cleveland proposed to restore the queen to power in return for amnesty to the revolutionists. The provisional government controlled by the sugar planters refused to give up power, however, and on July 4, 1894, it created the Republic of Hawaii, which included in its constitution a provision for American annexation. In 1897, when William McKinley became president, he was looking for an excuse to annex the islands. “We need Hawaii,” he claimed, “just as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is manifest destiny.” When the Senate could not muster the two-thirds majority needed to approve an annexation treaty, McKinley used a joint resolution of the House and the Senate to achieve his aims. The resolution passed by simple majorities in both houses, and Hawaii was annexed by the United States in the summer of 1898.

The War of 1898

Until the 1890s, reservations about acquiring overseas possessions had checked America’s drive to expand. Suddenly, in 1898 and 1899, such inhibitions collapsed, and the United States aggressively thrust its way to the far reaches of Asia. The spark for this explosion of imperialism lay not in Asia but in Cuba, a Spanish colony ninety miles southwest of the southern tip of Florida. Ironically, the chief motive was a sense of outrage at another country’s imperialism. Americans wanted the Cubans to gain their independence from Spain.

“CUBA LIBRE” Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, Cubans had repeatedly revolted against centuries-old Spanish rule, only to be ruthlessly suppressed. As one of Spain’s oldest colonies, Cuba was a major export market for the mother country. Yet American sugar and mining companies had also invested heavily in Cuba. The United States in fact traded more with Cuba than Spain did.

On February 24, 1895, insurrection again broke out as Cubans waged guerrilla warfare against Spanish troops. Events in Cuba supplied dramatic headlines for newspapers and magazines. William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World were at the time locked in a monumental competition for readers, striving to outdo each other with sensational headlines about every Spanish atrocity in Cuba, real or invented. The newspapers’ sensationalism as well as their intentional efforts to manipulate public opinion came to be called yellow journalism. Hearst wanted a war against Spain to catapult the United States into global significance. Once war was declared against Spain, Hearst took credit for it. One of his newspaper headlines blared: “HOW DO YOU LIKE THE JOURNAL’S WAR?” pressure for war At the outset of the Cuban rebellion in 1895, President Grover Cleveland tried to protect U. S. business interests in Cuba while avoiding military involvement. Mounting public sympathy for the rebel cause prompted acute concern in Congress, however. By concurrent resolutions on April 6, 1896, the House and Senate endorsed the granting of official recognition to the Cuban rebels. After his inauguration in March 1897, President William McKinley continued the posture of sympathetic neutrality, but with each passing month Americans called for greater assistance to the Cuban insurgents. In 1897, Spain offered Cubans autonomy (self-government without formal independence) in return for ending the rebellion. The Cubans rejected the offer. Spain was impaled on the horns of a dilemma, unable to end the insurrection and unready to give up Cuba.

Early in 1898, events pushed the two nations into a war that neither government wanted. On January 25, the U. S. battleship Maine docked in Havana harbor, ostensibly on a courtesy call. On February 9, the New York Journal released the text of a letter from the Spanish ambassador Depuy de Lome to a friend in Havana. In the so-called de Lome letter, which had been stolen from the post office by a Cuban spy, de Lome called President McKinley “weak and a bidder for the admiration of the crowd, besides being a would-be politician who tries to leave a door open behind himself while keeping on good terms with the jingoes of his party.” De Lome resigned to prevent further embarrassment to his government.

Six days later, during the night of February 15, 1898, the Maine exploded and sank in Havana harbor, with a horrible loss of 260 men. Although years later the sinking was ruled an accident resulting from a coal explosion, those eager for a war with Spain in 1898 saw no need to withhold judgment. Upon learning about the loss of the Maine, the 39-year-old assistant secretary of the navy, Theodore Roosevelt, told a friend that he “would give anything if President McKinley would order the fleet to Havana tomorrow.” He called the sinking “an act of dirty treachery on the part of the Spaniards.” The United States, he claimed, “needs a war.” The outcry against Spain rose in a crescendo with the words “Remember the Maine!”

The weight of outraged public opinion and the influence of Republican militants such as Roosevelt and the president’s closest friend, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, eroded McKinley’s neutrality. On April 11, McKinley asked Congress for authority to use armed forces in Cuba. On April 20, Congress declared Cuba independent and demanded the withdrawal of Spanish forces. The Teller Amendment, added on the Senate floor to the war resolution, disclaimed any U. S. designs on Cuban territory. McKinley signed the war resolution, and a copy went off to the Spanish government. McKinley called for 125,000 volunteers to supplement the 28,000 men in the U. S. Army. Among the first to enlist was the man who most lusted for war against Spain: Theodore Roosevelt. Never has an American war, so casually begun and so enthusiastically supported, generated such unexpected and far-reaching consequences.

The sinking of the Maine in Havana Harbor

The uproar created by the incident and its coverage in the “yellow press” helped to push President William McKinley to declare war.

MANILA The war with Spain lasted only 114 days. The conflict was barely under way before the U. S. Navy produced a spectacular victory in an unexpected location in the Pacific Ocean: Manila Bay in the Philippines. Just before war had been declared, Theodore Roosevelt, still serving as the assistant secretary of the navy, had ordered (without getting the permission of his superiors) Commodore George Dewey, commander of the small U. S. fleet in Asia, to engage Spanish forces in the Philippines in case of war in Cuba. Commodore Dewey arrived late on April 30 with four cruisers and two gunboats, and they quickly destroyed or captured all the outdated Spanish warships in Manila Bay without suffering any major damage themselves. Dewey was now in awkward possession of the bay without any ground forces to go onshore. Promised reinforcements, he stayed while German and British warships cruised offshore like watchful vultures, ready to take control of the Philippines if the United States did not do so. In the meantime,

Turmoil in the Philippines

Emilio Aguinaldo (seated third from right) and other leaders of the Filipino insurgency.

Emilio Aguinaldo, the leader of the Filipino nationalist movement, declared the Philippines independent on June 12. With Aguinaldo’s help, Dewey’s forces entered Manila on August 13. The Spanish garrison preferred to surrender to the Americans rather than to the vengeful Filipinos. News of the American victory sent President McKinley scurrying to find a map of Asia to locate “these darned islands” now occupied by U. S. soldiers and sailors.

THE CUBAN CAMPAIGN While these events transpired halfway around the world, the fighting in Cuba reached a surprisingly quick climax. The U. S. Navy blockaded the Spanish navy inside Santiago harbor while some 17,000 American troops hastily assembled at Tampa, Florida. One prominent unit was the First Volunteer Cavalry, better known as the Rough Riders, a regiment with “special qualifications” made up of former Ivy League athletes, ex-convicts, Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Pawnee, and Creek Indians, and southwestern sharpshooters. Of course, the Rough Riders are best remembered because Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt was second in command. One of the Rough Riders said that Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt was “nervous, energetic, virile. He may wear out some day, but he will never rust out.” When the 578 Rough Riders, accompanied by a gaggle of reporters and photographers, landed in oppressive heat on

June 22, 1898, at the undefended southeastern tip of Cuba, chaos ensued, as their horses and mules were mistakenly sent elsewhere, leaving the Rough Riders to become the “Weary Walkers.” Only Roosevelt ended up with his horse, Little Texas.

Land and sea battles around Santiago quickly broke Spanish resistance. On July 1, about seven thousand U. S. soldiers took the fortified village of El Caney. While a much larger force attacked San Juan Hill, a smaller unit, including the dismounted Rough Riders together with African American soldiers from two cavalry units, with Roosevelt at their head yelling “Charge!”, seized nearby Kettle Hill. A friend wrote to Roosevelt’s wife that her husband was “reveling in victory and gore.” to widespread media coverage, much of it exaggerated, Roosevelt had become a home-front legend, the most beloved hero of the brief war.

On July 26, 1898, the Spanish government in Madrid sued for peace. After discussions lasting two weeks, an armistice was signed on August 12, less than four months after the war’s start and the day before Americans entered Manila. In Cuba, the Spanish forces formally surrendered to the U. S. commander, boarded ships, and sailed for Spain. Excluded from the ceremony were the Cubans, for whom the war had been fought. The peace treaty specified that Spain should give up Cuba and that the United States should annex Puerto Rico and occupy Manila pending the transfer of power in the Philippines.

In all, over 60,000 Spanish soldiers died of disease or wounds in the four-month war. Among the 274,000 Americans who served during the war, 5,462 died, but only 379 in battle. Most succumbed to malaria, typhoid, dysentery, or yellow fever. At such a cost the United States was launched onto the world scene as a great power, with all the benefits—and burdens—of a new colonial empire of its own.

America’s role in the world was changed forever by the campaign, for the United States emerged as an imperial power. Halfway through the brief conflict in Cuba, John Hay, soon to be secretary of state, wrote a letter to his close friend, Theodore Roosevelt. In acknowledging Roosevelt’s trial by fire, Hay called it “a splendid little war, begun with the highest motives, carried on with magnificent intelligence and spirit, favored by that fortune that loves the brave.” Victory in the War of 1898 boosted American self-confidence and reinforced the self-serving American belief, tinged with racism, that the nation had a “manifest destiny” to reshape the world in its own image. As Josiah Strong had boasted in 1895, Americans “are a race of unequaled energy” who represent “the largest liberty, the purest Christianity, the highest civilization” in the world. “Can anyone doubt that this race. . . is destined to dispossess many weaker races, assimilate others, and mold the remainder until. . . it has Anglo-Saxonized mankind?” The United States liberated Spain’s remaining colonies, yet in some cases it would substitute its own oppression for Spain’s. If war with Spain saved many lives by ending the insurrection in Cuba, it also led the United States to suppress another anti-colonial insurrection, in the Philippines, and the acquisition of its own imperial colonies created a host of festering problems that persisted into the twentieth century.

THE DEBATE OVER ANNEXATION The United States and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898, ending the war between the two nations. It granted Cuba its independence, but the status of the Philippines remained unresolved. American business leaders wanted to keep the Philippines so that they could more easily penetrate the vast markets of populous China. Missionary societies also wanted the United States to annex the Philippines so that they could bring Christianity to “the little brown brother.” The Philippines promised to provide a useful base for all such activities. President McKinley pondered the alternatives and later explained his reasoning for annexing the Philippines to a group of fellow Methodists:

And one night late it came to me this way—I don’t know how it was, but it came: (1) that we could not give them back to Spain—that would be cowardly and dishonorable; (2) that we could not turn them over to France or Germany—our commercial rivals in the Orient—that would be bad business and discreditable; (3) that we could not leave them to themselves—they were unfit for self-government—and they would soon have anarchy and misrule over there worse than Spain’s was; and (4) that there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellowmen for whom Christ also died. And then I went to bed, and went to sleep and slept soundly.

In one brief statement, McKinley had summarized the motivating ideas of American imperialism: (1) national glory, (2) commerce, (3) racial superiority, and (4) evangelism. American negotiators in Paris finally offered the Spanish $20 million for the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam, a Spanish-controlled island in the Pacific with a valuable harbor.

Meanwhile, Americans had taken other giant steps in the Pacific. Congress had annexed Hawaii in the midst of the War of 1898. In 1898, the United States had also claimed Wake Island, located between Guam and the

Hawaiian Islands, which would become a vital link in a future transpacific telegraph cable. Then, in 1899, Germany and the United States agreed to partition the Samoa islands. The United States annexed the easternmost islands; Germany took the rest.

By early 1899, the Treaty of Paris, ending the War of 1898, had yet to be ratified in the Senate, where most Democrats and Populists and some Republicans opposed it. Anti-imperialists argued that acquisition of the Philippines would corrupt the American principle dating back to the Revolution that people should be self-governing rather than colonial subjects. Opponents also noted the inconsistency of liberating Cuba and annexing the Philippines, as well as the danger that the Philippines would become impossible to defend if a foreign power such as Japan attacked. The opposition might have been strong enough to kill the treaty had not the Democrat William Jennings Bryan influenced the vote for approval. Ending the war, he argued, would open the way for the future independence of the Philippines. His support convinced enough Democrats to enable passage of the peace treaty in the Senate on February 6, 1899, by the narrowest of margins: only one vote more than the necessary two thirds.

President McKinley, however, had no intention of granting the Philippines independence. He insisted that the United States take control of the islands as an act of “benevolent assimilation.” In February 1899, an American soldier outside Manila fired on soldiers in the Filipino Army of Liberation, and two of them were killed. Suddenly, the United States found itself in a new war, this time a crusade to suppress the Filipino independence movement. Since Aguinaldo’s forces, called insurrectos, were more or less in control of the islands outside Manila, what followed was largely a brutal American war of conquest.

THE PHILIPPINE-AMERICAN WAR The American effort to quash Filipino nationalism lasted three years, eventually involved some 126,000 U. S. troops, and took the lives of hundreds of thousands of Filipinos (most of them civilians) and 4,234 American soldiers. It was a sordid conflict, with grisly massacres committed by both sides. It did not help matters that many American soldiers referred to their Filipino opponents as “niggers.” Within the first year of the war in the Philippines, American newspapers had begun to report an array of atrocities committed by U. S. troops—villages burned, prisoners tortured and executed. Thus did the United States alienate and destroy a Filipino independence movement modeled after America’s own struggle for independence from Great Britain. Organized Filipino resistance had collapsed by the end of

1899, but even after the American capture of Aguinaldo in 1901, sporadic guerrilla action lasted until mid-1902.

Against the backdrop of this nasty guerrilla war, the great debate over imperialism continued in the United States. In 1899 several anti-imperialist groups combined to form the American Anti-Imperialist League. The league attracted members representing many shades of opinion. Former presidents Grover Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison urged President McKinley to withdraw U. S. forces from the Philippines. Andrew Carnegie footed the bills for the League; and on imperialism, at least, the union leader Samuel Gompers agreed with the steel king. Presidents Charles Eliot of Harvard and David

Starr Jordan of Stanford University supported the group, along with the social reformer Jane Addams. The drive for imperialism, said the philosopher William James, had caused the nation to “puke up its ancient soul.”

ORGANIZING THE ACQUISITIONS In the end the imperialists won the debate over the status of the territories acquired from Spain. Senator Beveridge boasted in 1900: “The Philippines are ours forever. And just beyond the Philippines are China’s illimitable markets. We will not retreat from either. . . . The power that rules the Pacific is the power that rules the world.” On July 4, 1901, the U. S. military government in the Philippines came to an end, and Judge William Howard Taft became the civil governor. The Philippine Government Act, passed by Congress in 1902, declared the Philippine Islands an “unorganized territory” and made the inhabitants citizens of the Philippines. In 1917, the Jones Act affirmed America’s intention to grant the Philippines independence on an unspecified date. Finally, the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934 offered independence after ten more years. The Philippines would finally become independent on July 4, 1946.

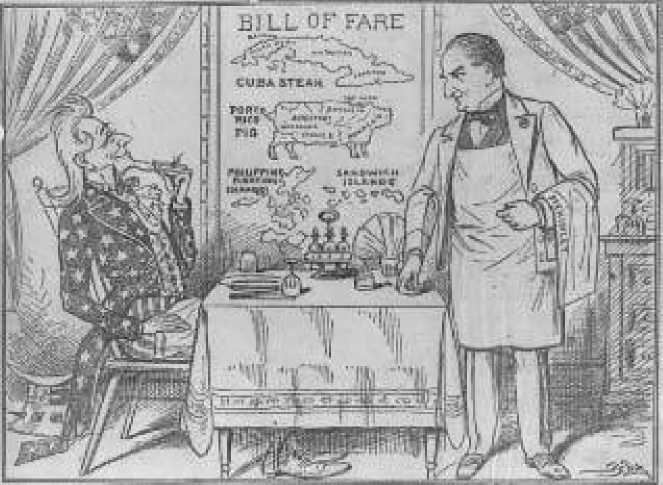

“WeU, I Hardly Know Which to Take First! ”

At the end of the nineteenth century, it seemed that Uncle Sam had developed a considerable appetite for foreign territory.

Closer to home, Puerto Rico had been acquired in part to serve as a U. S. outpost guarding the approach to the Caribbean Sea and any future isthmian canal in Central America. On April 12, 1900, the Foraker Act established a government on the island. The president appointed a governor and eleven members of an executive council, and an elected House of Delegates made up the lower house of the legislature. Residents of the island were declared citizens of Puerto Rico; they were not made citizens of the United States until 1917, when the Jones Act granted them U. S. citizenship and made both houses of the legislature elective. In 1947 the governor also became elective, and in 1952 Puerto Rico became a commonwealth with its own constitution and elected officials, a unique status. Like a state, Puerto Rico is free to change its constitution insofar as it does not conflict with the U. S. Constitution.

Finally, there was Cuba. Having liberated the Cubans from Spanish rule, the Americans found themselves propping up a shaky new government whose economy was in shambles. Technically, Cuba had not gained its independence in 1898. Instead, it remained a protectorate of the United States. American troops remained in control of Cuba for four years, after which they left, but on the condition that the United States could intervene again if the political conditions in Cuba did not satisfy American expectations. Clashes between U. S. soldiers and Cubans erupted almost immediately. When President McKinley set up a military government for the island late in 1898, it was at odds with rebel leaders from the start. The United States finally fulfilled the promise of independence after the military regime had restored order, organized schools, and improved sanitary conditions. The problem of disease in Cuba prompted the work of Dr. Walter Reed, who made an outstanding contribution to health in tropical regions around the world. Named head of the Army Yellow Fever Commission in 1900, he proved that mosquitoes carried yellow fever. The commission’s experiments led the way to effective control of the disease worldwide.

In 1900, on President McKinley’s order, Cubans drafted a constitution modeled on that of the United States. The Platt Amendment, added to an army appropriations bill passed by Congress in 1901, sharply restricted the new Cuban government’s independence, however. The amendment required that Cuba never impair its independence by signing a treaty with a third power, that it keep its debt within the government’s power to repay it out of ordinary revenues, and that it acknowledge the right of the United States to intervene in Cuba whenever it saw fit. Finally, Cuba had to sell or lease to the United States lands to be used for coaling or naval stations, a proviso that led to a U. S. naval base at Guantanamo Bay, which still exists today.

Imperial Rivalries in East Asia

During the 1890s, the United States was not the only nation to emerge as a world power. Japan defeated China in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). China’s weakness enabled European powers to exploit it. Russia, Germany, France, and Great Britain established spheres of influence in China by the end of the century. In early 1898 and again in 1899, the British asked the American government to join them in preserving the territorial integrity of China against further imperialist actions. Both times the Senate rejected the request because it risked an entangling alliance in a region— Asia—where the United States as yet had no strategic investment.

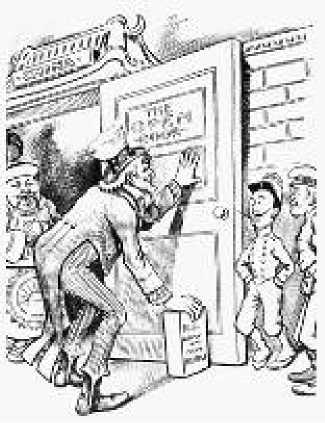

“The Open Door”

Cartoon depicting Uncle Sam propping open a door for China with a brick labeled “U. S. Army and Navy Prestige,” as colonial powers look on.

The “open door” The American outlook toward Asia changed with the defeat of Spain and the acquisition of the Philippines. Instead of acting jointly with Great Britain, however, the U. S. government decided to act alone. What came to be known as the Open Door policy was outlined in Secretary of State John Hay’s Open Door Note, dispatched in 1899 to his European counterparts. It proposed to keep China open to trade with all countries on an equal basis. More specifically, it called upon foreign powers, within their spheres of influence, (1) to refrain from interfering with any treaty port (a port open to all by treaty) or any vested interest, (2) to permit Chinese authorities to collect tariffs on an equal basis, and (3) to show no favors to their own nationals in the matter of harbor dues or railroad charges. As it turned out, none of the European powers except Britain accepted Hay’s principles, but none rejected them either. So Hay simply announced that all the major powers involved in China had accepted the policy.

The Open Door policy was rooted in desire of American businesses to exploit Chinese markets. However, it also tapped the deep-seated sympathies of those who

Opposed imperialism, especially as the policy pledged to protect China’s territorial integrity. But the much-trumpeted Open Door policy had little legal standing. When the Japanese, concerned about Russian pressure in Manchuria, asked how the United States intended to enforce the policy, Hay replied that America was “not prepared. . . to enforce these views.” So it would remain for forty years, until continued Japanese expansion in China would bring America to war in 1941.

Big-Stick Diplomacy

More than any other American of his time, Theodore Roosevelt transformed the role of the United States in world affairs. The nation had emerged from the War of 1898 a world power with major new responsibilities. To ensure that the United States accepted its international obligations, Roosevelt stretched both the Constitution and executive power to the limit. In the process he pushed a reluctant nation onto the center stage of world affairs.

Roosevelt’s rise Born in 1858, Roosevelt had grown up in Manhattan in cultured comfort, had visited Europe as a child, spoke German fluently, and had graduated from Harvard with honors in 1880. A sickly, scrawny boy with poor eyesight and chronic asthma, he built himself up into a physical and intellectual athlete, a man of almost superhuman energies who became a lifelong practitioner of the “strenuous life.” Roosevelt loved rigorous exercise and outdoor activities. A boxer, wrestler, mountain climber, hunter, and outdoorsman, he also displayed extraordinary intellectual curiosity. He became a voracious reader, a learned natural scientist, dedicated bird-watcher, a renowned historian and essayist, and a zealous moralist. He wrote thirty-eight books on a wide variety of subjects. His boundless energy and fierce competitive spirit were infectious, and he was ever willing to express an opinion on any subject. Within two years of graduating from Harvard, Roosevelt won election to the New York legislature. “I rose like a rocket,” he later observed.

But with the world seemingly at his feet, disaster struck. In 1884, Roosevelt’s beloved mother Mittie, only forty-eight years old, died. Eleven hours later, in the same house, his twenty-two-year-old wife Alice died in his arms of kidney failure, having recently given birth to their only child. The double funeral was so wrenching that the officiating minister wept throughout his prayer. In an attempt to recover from this “strange and terrible fate,” a distraught Roosevelt turned his baby daughter Alice over to his sister, quit his political career, sold the family house, and moved west to take up cattle ranching in the Dakota Territory. The blue-blooded New Yorker escaped his grief by plunging himself into virile western life: he relished hunting big game, leading cattle roundups, capturing outlaws, fighting indians (whom he termed a “lesser race”)—and reading novels by the campfire. Although his western career lasted only two years, he never got over being a cowboy.

Back in New York City, Roosevelt remarried and ran unsuccessfully for mayor in 1886; he later served six years as civil service commissioner and two years as New York City’s police commissioner. In 1896, Roosevelt campaigned hard for William McKinley, and the new president was asked to reward him with the position of assistant secretary of the navy. McKinley initially balked, saying that young Roosevelt was too “hotheaded,” but he eventually relented and appointed the war-loving aristocrat. Roosevelt took full advantage of his celebrity with the Rough Riders during the war in Cuba to win the governorship of New York in November 1898. By then he had become the most prominent Republican in the nation.

In the 1900 presidential contest, the Democrats turned once again to William Jennings Bryan, who sought to make American imperialism the “paramount issue” of the campaign. The Democratic platform condemned the Philippine conflict as “an unnecessary war” that had placed the United States “in the false and un-American position of crushing with military force the efforts of our former allies to achieve liberty and self-government.”

The Republicans welcomed the chance to disagree. They renominated McKinley and named Theodore Roosevelt, now virtually Mr. Imperialism, his running mate. Roosevelt’s much-publicized combat exploits in Cuba had made him a national celebrity. Colonel Roosevelt was named “Man of the Year” in 1898. Elected governor of New York that year, Roosevelt nevertheless leapt at the chance to be vice president in part because he despised Bryan as a dangerous “radical” who called for the federal government to take ownership of railroads. Roosevelt was more than a match for Bryan as a campaign speaker, and he crisscrossed the nation on behalf of McKinley, speaking in opposition to Bryan’s “communistic and socialistic doctrines” promoting higher taxes and the free coinage of silver. McKinley outpolled Bryan by 7.2 million to 6.4 million popular votes and 292 to 155 electoral votes. Bryan even lost his own state of Nebraska.

Less than a year after McKinley’s victory, however, his second term ended tragically. On September 6, 1901, at a reception at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, an unemployed anarchist named Leon Czolgosz (pronounced chole-gosh) approached the fifty-eight-year-old president with a

Gun concealed in a bandaged hand and fired at point-blank range.

Mr. Imperialism

This 1900 cartoon shows the Republican vice-presidential candidate, Theodore Roosevelt, overshadowing his running mate, President William McKinley.

McKinley died eight days later, and Theodore Roosevelt was elevated to the White House. “Now look,” erupted Marcus “Mark” Hanna, the Ohio businessman and politico,

“that damned cowboy is President of the United States!”

Six weeks short of his forty-third birthday, Roosevelt was the youngest man ever to reach the White House, but he had more experience in public affairs than most and perhaps more vitality than any. One observer compared him to Niagara Falls, “both great wonders of nature.” Even Woodrow Wilson, Roosevelt’s main political opponent, said that the former

“Rough Rider” was “a great big boy” at heart. “You can’t resist the man.” Roosevelt’s glittering spectacles, glistening teeth, and overflowing gusto were a godsend to the cartoonists, who added another trademark when he pronounced the adage “Speak softly, and carry a big stick.”

Along with Roosevelt’s boundless energy went a sense of unshakable self-righteousness, which led him to cast nearly every issue in moral and patriotic terms. He was the first truly activist president. He considered the presidency his “bully pulpit,” and he delivered fist-pumping speeches on the virtues of righteousness, honesty, civic duty, and strenuosity. Nowhere was President Roosevelt’s forceful will more evident than in his conduct of foreign affairs.

THE PANAMA CANAL After the War of 1898, the United States became more deeply involved in the Caribbean. One issue overshadowed every other in the region: the Panama Canal. The narrow isthmus of Panama had first become a major concern of Americans in the late 1840s, when it became an important overland route to the California goldfields. Two treaties dating from that period loomed years later as obstacles to the construction of a canal. The Bidlack Treaty (1846) with Colombia (then New Granada) guaranteed both Colombia’s sovereignty over Panama and the

Neutrality of the isthmus. In the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty (1850) the British agreed to acquire no more Central American territory, and the United States joined them in agreeing to build or fortify a canal only by mutual consent.

After the War of 1898, Secretary of State John Hay asked the British ambassador for such consent. The outcome was the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty of 1901. Other obstacles remained, however. From 1881 to 1887, a French company under Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had engineered the Suez Canal in Egypt between 1859 and 1869, had spent nearly $300 million and some twenty thousand lives to dig less than a third of a canal across Panama, still under the control of Colombia. The company asked that the United States purchase its holdings, which it did. Meanwhile, Secretary Hay had opened negotiations with Ambassador Tomas Herran of Colombia. In return for acquiring a canal zone six miles wide, the United States agreed to pay $10 million in cash and a rental fee of $250,000 a year. The U. S. Senate ratified the Hay-Herran Treaty in 1903, but the Colombian senate held out for $25 million in cash. In response to this act by those “foolish and homicidal corruptionists in Bogota,” Theodore Roosevelt, by then president, flew into a rage. Meanwhile the Panamanians revolted against Colombian

Rule. Philippe Bunau-Varilla, an

Digging the canal

President Theodore Roosevelt operating a steam shovel during his 1906 visit to the Panama Canal.

Employee of the French canal company, assisted them, and reported, after visiting Roosevelt and Hay in Washington, D. C., that American warships would arrive at Colon, Panama, on November 2.

The Panamanians revolted the next day. Colombian troops, who could not penetrate the overland jungle, found U. S. ships blocking the sea-lanes. On November 13, the Roosevelt administration received its first ambassador from Panama, who happened to be Philippe Bunau-Varilla; he eagerly signed a treaty that extended the Canal zone from six to ten miles in width. For $10 million down and $250,000 a year, the United States received “in perpetuity the use, occupation and

Why did America want to build the Panama Canal? How did the U. S. government interfere with Colombian politics in an effort to gain control of the canal? What was the Roosevelt Corollary?

Control” of the Canal Zone. The U. S. attorney general, asked to supply a legal opinion upholding Roosevelt’s actions, responded wryly, “No, Mr. President, if I were you I would not have any taint of legality about it.” Roosevelt later explained that “I took the Canal Zone and let Congress debate; and while the debate goes on the [construction of the] Canal does also.” The strategic canal opened on August 15, 1914, two weeks after the outbreak of World War I in Europe.

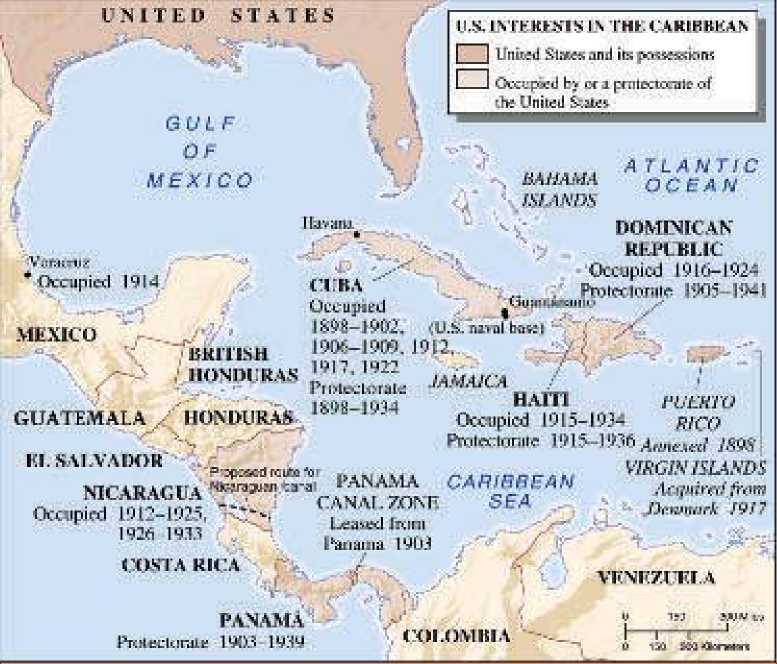

THE ROOSEVELT COROLLARY The behavior of the United States in gaining control of the Panama Canal created ill will throughout Latin America that would last for generations. Equally galling to Latin American sensibilities was the United States’ constant meddling in the internal affairs of

Various nations. A prime excuse for intervention in those days was to force the collection of debts owed to foreign corporations. In 1904, a crisis over the debts of the Dominican Republic prompted Roosevelt to formulate U. S. policy in the Caribbean. In his annual address to Congress in 1904, he outlined what came to be known as the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine: the principle, in short, that since the Monroe Doctrine prohibited intervention in the region by Europeans, the United States was justified in intervening first to forestall involvement by outsiders.

The world’s policeman

President Theodore Roosevelt wields “the big stick,” symbolizing his aggressive diplomacy.

THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR In east Asia, meanwhile, the principle of equal trading rights embodied in the Open Door policy was tested when rivalry between Russia and Japan flared into warfare. By 1904 the Japanese had decided that the Russians threatened their ambitions in China and Korea. On February 8, Japanese warships devastated the Russian fleet. The Japanese then occupied the Korean peninsula and drove the Russians back into Manchuria. When the Japanese signaled that they would welcome a negotiated settlement, Roosevelt sponsored a peace conference in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. With the Treaty of Portsmouth, signed on September 5, 1905, the concessions all went to the Japanese. Russia acknowledged Japan’s “predominant political, military, and economic interests in Korea” (Japan would annex the kingdom in 1910), and both powers agreed to evacuate Manchuria.

Japan’s show of strength against Russia raised doubts among American leaders about the security of the Philippines. During the Portsmouth talks, Roosevelt sent William Howard Taft to meet with the Japanese foreign minister in Tokyo. The two men negotiated the Taft-Katsura Agreement of July 29, 1905, in which the United States accepted Japanese control of Korea, and Japan disavowed any designs on the Philippines. Three years later the Root-Takahira Agreement, negotiated by Secretary of State Elihu Root and the Japanese ambassador, endorsed the status quo and reinforced the Open

Door policy by supporting “the independence and integrity of China” and “the principle of equal opportunity for commerce and industry in China.” Behind the diplomatic facade of goodwill, however, lay mutual distrust. For many Americans the Russian threat in east Asia now gave way to concerns about the “yellow peril” (a term apparently coined by Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany). Racial animosities on the West Coast helped sour relations with Japan. In 1906, San Francisco’s school board ordered students of Asian descent to attend a separate public school. The Japanese government sharply protested such prejudice, and President Roosevelt persuaded the school board to change its policy, but only after making sure that Japanese authorities would not issue “visas” to “laborers,” except former residents of the United States; the parents, wives, or children of residents; or those who already possessed an interest in an American farming enterprise. This “Gentlemen’s Agreement” of 1907, the precise terms of which have never been revealed, halted the influx of Japanese immigrants and brought some respite to racial agitation in California.

THE GREAT WHITE FLEET Before Roosevelt left the White House in early 1909, he celebrated America’s rise to the status of a world power with one great flourish. In 1907, he sent the entire U. S. Navy, by then second in strength only to the British fleet, on a grand tour around the world, announcing that he was ready for “a feast, a frolic, or a fight.” He got mostly the first two and none of the last. At every port of call down the Atlantic coast of South America, up the west coast, out to Hawaii, and down to New Zealand and Australia, the “Great White Fleet” received rousing welcomes. The triumphal procession continued home by way of the Mediterranean and steamed back into American waters in early 1909, just in time to close out Roosevelt’s presidency on a note of success.

Yet it was a success that would have mixed consequences. Roosevelt’s effort to deploy American power abroad was accompanied by a racist ideology shared by many prominent political figures of the time. He once told the graduates of the Naval War College that all “the great masterful races have been fighting races, and the minute that a race loses the hard fighting virtues. . . it has lost the right to stand as equal to the best.” On another occasion he called warfare the best way to promote “the clear instinct for race selfishness” and insisted that “the most ultimately righteous of all wars is a war with savages.” Such a belligerent, self-righteous bigotry defied America’s egalitarian ideals and would come back to haunt the United States in world affairs—and at home.

World History

World History