Although the events leading to the Revolution centered primarily on the conflicts between British authority and colonial urban commerce, the vast rural populace played an essential supporting role in the independence movement. How can we explain the willingness of wealthy southerners and many poor farmers to support a rebellion that was spearheaded by an antagonized merchant class? Though certainly no apparent allied economic interests were shared among these groups, each group had its own motives for resisting British authority. In rural America, antagonisms primarily stemmed from English land policy (Economic Reasoning Proposition 2, choices impose costs).

Before 1763, British policy had been calculated to encourage the rapid development of the colonial West. In the interest of trade, English merchants wanted the new country to be populated as rapidly as possible. Moreover, rapid settlement extended the frontier and thereby helped strengthen opposition to France and Spain. By 1763, however, the need to fortify the frontier against foreign powers had disappeared. As the Crown and Parliament saw it, now was the time for more control on the frontier. First, the British felt it was wise to contain the population well within the seaboard area, where the major investments had been made and where political control would be easier. Second, the fur trade was now under the complete control of the British, and it was deemed unwise to have frontier pioneers moving in and creating trouble with the Indians. Third, wealthy English landowners were purchasing western land in great tracts, and pressure was exerted to “save” some of the good land for these investors. Finally, placing the western lands under the direct control of the Crown was designed to obtain revenues from sales and quitrents for the British treasury.30

In the early 1760s, events on the frontier served to tighten the Crown’s control of settlement. Angry over injustices and fearful that the settlers would encroach on their hunting grounds, the northern Indians rebelled under the Ottawa chief Pontiac. Colonial and British troops put down the uprising, but only after seven of the nine British garrisons west of Niagara were destroyed. Everyone knew that western settlement would come

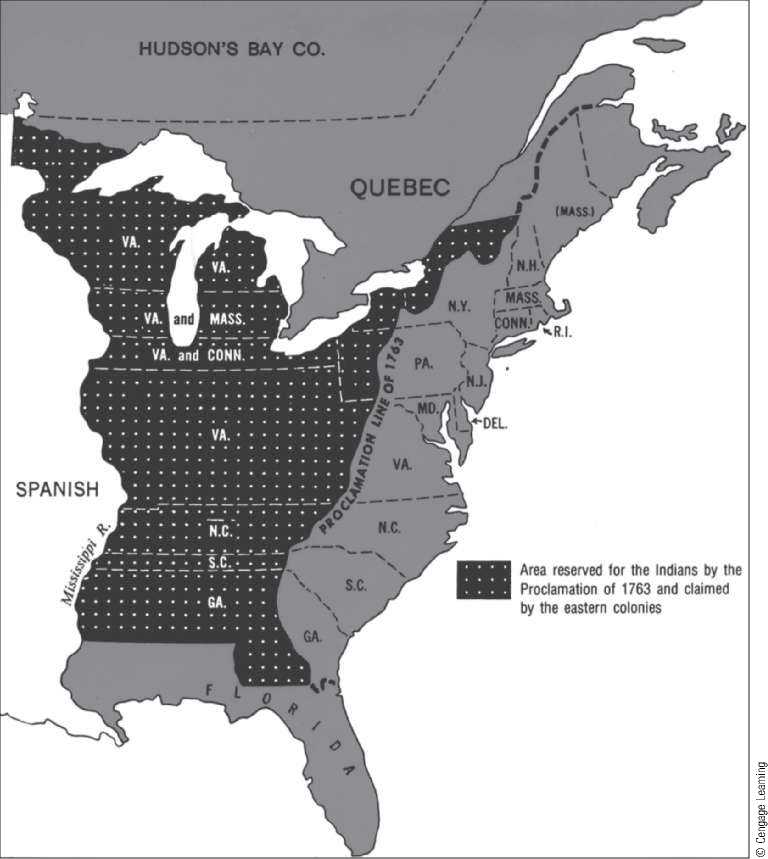

Under continuing threat unless the native Indians were pacified. Primarily as a temporary solution, the king issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which, in effect, drew a line beyond which colonials could not settle without express permission from the Crown (see Map 6.1). Governors could no longer grant patents to land lying west of the sources of rivers that flowed into the Atlantic; anyone seeking such a grant had to obtain one directly from the king. At the same time, the fur trade was placed under centralized control, and no trader could cross the Allegheny Mountains without permission from England.

A few years later, the policy of keeping colonial settlement under British supervision was reaffirmed, although it became apparent that the western boundary line would not remain rigidly fixed. In 1768, the line was shifted westward, and treaties with the Indians made large land tracts available to speculators. In 1774, the year in which the Intolerable Acts were passed, two British actions demonstrated that temporary expedients had evolved into permanent policies. First, a royal proclamation tightened the terms on

MAP 6.1

Colonial Land Claims

The colonial appetite for new land was huge, as colonial land claims demonstrated. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was designed to stop westward movement.

Which land would pass into private hands. Grants were no longer to be free; instead, tracts were to be sold at public auctions in lots of 100 to 1,000 acres at a minimum price of 6d. per acre. Even more serious was the passage of the Quebec Act in 1774, which changed the boundaries of Quebec to the Ohio River in the East and the Mississippi River in the West (see Map 6.2). More important, the act destroyed the western land claims of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Virginia. The fur trade was to be regulated by the governor of Quebec, and the Indian boundary line was to run as far south as Georgia. Many colonists viewed the act as theft.

Not all colonists suffered from the new land policy. Rich land speculators who were politically powerful enough to obtain special grants from the king found the new regulations restrictive but not ruinous. Indeed, great holders of ungranted lands east of the mountains, such as the Penns and the Calverts, or of huge tracts already granted but not yet settled, stood to benefit from the rise in property values that resulted from the British embargo on westward movement. Similarly, farmers of old, established agricultural areas would benefit in two ways: (1) the competition from the produce of the new

MAP 6.2

Reassignment of Claims

The Quebec Act of 1774 gave the Indians territories that earlier had been claimed by various colonies and, at the same time, nearly doubled the area of Quebec.

Lands would now be less and (2) because it would be harder for agricultural laborers to obtain their own farms, hired hands would be cheaper.

Although many of the restrictions on westward movement were necessary, at least for a time because of Indian resistance on the frontier, many colonists resented these restrictions. The withdrawal of cheap, unsettled western lands particularly disillusioned young adults who had planned to set out on their own but now could not. Recall that from 1720 to 1775, about 225,000 Scotch-Irish and Germans had immigrated to America, mostly to the Middle colonies. These were largely men of fighting age with no loyalties to the English Crown. Now many had been denied land they saw as rightfully theirs. Similarly, even established frontier farmers usually took an anti-British stand because they thought that they would be more likely to succeed under a government liberal in disposing of its land. Although poor agrarians did not have dollar stakes in western lands that were comparable to those of large fur traders, land speculators, and planters, they were still affected. Those who were unable to pay their debts sometimes lost their farms through foreclosure; a British policy that inhibited westward movement angered the frontiersmen and tended to align them against the British and with the aristocratic Americans, with whom they had no other affiliation. The Currency Act (Restraining Act) of 1764 also frustrated and annoyed this debtor group because, although prices actually rose moderately in the ensuing decade, farmers were persuaded that their lot worsened with the moderate contraction of paper money that occurred (Economic Reasoning Proposition 4, laws and rules matter).

World History

World History