Although Jackson’s supporters liked to cast him as the political heir of Jefferson, he was in many ways like the conservative Washington: a soldier first, an inveterate speculator in western lands, the owner of a fine plantation and of many slaves, a man with few intellectual interests, and only sketchily educated.

Nor was Jackson quite the rough-hewn frontier character he sometimes seemed. True, he could not spell (again, like Washington), he possessed the unsavory habits of the tobacco chewer, and he had a violent temper. But his manners and lifestyle were those of a southern planter. “I have always felt that he was a perfect savage,” Grace Fletcher Webster, wife of Senator Daniel Webster, explained. “But,” she added, “his manners are very mild and gentlemanly.” Jackson’s judgment was intuitive yet usually sound; his frequent rages were often feigned, designed to accomplish some carefully thought-out purpose. Once, after scattering a delegation of protesters with an exhibition of wrath, he turned to an observer and said impishly, “They thought I was mad.”

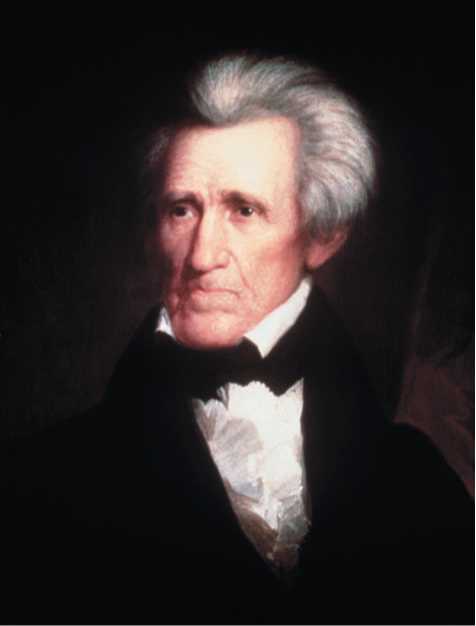

Andrew Jackson as president.

Whatever his personal convictions, Jackson stood as the symbol for a new, democratically oriented generation. That he was both a great hero and in many ways a most extraordinary person helps explain his mass appeal. He had defeated a mighty British army and killed many Indians, but he acted on hunches and not always consistently, shouted and pounded his fist when angry, put loyalty to old comrades above efficiency when making appointments, and distrusted “aristocrats” and all special privilege. Perhaps he was rich, perhaps conservative, but he was a man of the people, born in a frontier cabin, and familiar with the problems of the average citizen.

Jackson epitomized many American ideals. He was intensely patriotic, generous to a fault, natural and democratic in manner (at home alike in the forest and in the ballroom of a fine mansion). He admired good horseflesh and beautiful women, yet no sterner moralist ever lived; he was a fighter, a relentless foe, but also a gentleman of sorts. That some special providence watched over him (as over the United States) appeared beyond argument to those who had followed his career. He seemed, in short, both an average and an ideal American—one the people could identify with and still revere.

For these reasons Jackson drew support from every section and every social class: western farmers and southern planters, urban workers and bankers, And merchants. In this sense he was profoundly democratic. He believed in equality of opportunity, distrusted entrenched status of every sort, and rejected no free American because of humble origins or inadequate education.

World History

World History