By 1951, the Ministry of State Security, now independent of the interior ministry, was the target of petitioners inquiring about the fate of those who disappeared during the Great Terror. By this time, most of those executed had been dead more than a decade. State-security minister S. D. Ignatiev wrote to Stalin's Politburo in October of 1951, describing how he proposed to handle the matter: 1

Ministry of State Security procedures have been to tell relatives of those executed that they were sentenced to ten years and sent to special regime camps without the right of correspondence. For the majority of cases, ten years have already passed, and such an answer is no longer appropriate. Without a death certificate, legal issues such as inheritance or remarriage cannot be resolved. Accordingly, relatives turn to party and judicial offices, to the leaders of the party and government, stubbornly insisting on conclusive answers.

The Ministry of State Security proposes to establish the following rule: Relatives of those executed more than ten years earlier are to be orally told that the sentenced person died in the place of confinement. . . . If necessary a death certificate can be issued.

To maintain secrecy, the lists of those sentenced to death will be maintained in the central office and responsible state-security employees will inform relatives at the locality.

Ignatiev's solution provided only stopgap relief from the flood of inquiries that became a torrent after Stalin's death in March of 1953. Stalin's successors were caught in a dilemma. Most had participated personally in Stalin's massacres; revelation of the scope of the Great Terror could threaten them. Also, official ideology continued (up until 1956) to present Stalin and the Politburo as omniscient and flawless. To come clean about Stalin's crimes would raise fundamental questions about the nature of the communist regime.

After a three-year power struggle from which Nikita Khrushchev (himself a notorious executioner under Stalin) emerged victorious, it was decided to reveal some of the truth to the party faithful at the Twentieth Party Congress of February 1956. Khrushchev's "secret speech,” which did not remain secret for long, focused only on Stalin's purge of party leaders; he scarcely mentioned the massive killing and imprisonments of ordinary citizens. Khrushchev's anti-Stalin speech unleashed a violent reaction in the Eastern European satellite countries, the most prominent being the Hungarian revolution of 1956.

It fell to Stalin's successors to decide what to do with the inquiries concerning the fate of relatives pouring into state offices. On February 10, 1956, the head of the letters department of the Council of Ministers complained to the head of state, Nikolai Bulganin, about "letters from citizens with complaints about the organs of state security which are either not answering questions about the fate of relatives arrested in 1937-1938 or are giving contradictory answers.” Bulganin requested of KGB head I. Serov an explanation of current KGB procedures. The KGB's top secret response (two copies only) on April 5, 1956, less than two months after Khrushchev's secret speech, shows that Stalin's successors were still not ready to come clean:

The answer given to relatives inquiring about the fate of relatives sentenced to death by former troikas of the OGPU or NKVD, by Special Assemblies of the NKVD-MVD, and by Military Collegiums of the Supreme Court was, until September 1955, that they were "sentenced to ten years in prison without right of correspondence and that their location was not known." Such answers, naturally, did not satisfy and led to repeated complaints and petitions. For this reason, we discussed on June 19, 1954, and on August 13, 1955, changes in the procedure for examining such requests and giving more specific answers. The Central Committee also discussed on June 19, 1954, and August 13, 1955, whether to change the procedure and to give more direct answers. On August 13, 1955, it was decided that the KGB, in consultation with the prosecutor's office, come up with recommendations on this issue.

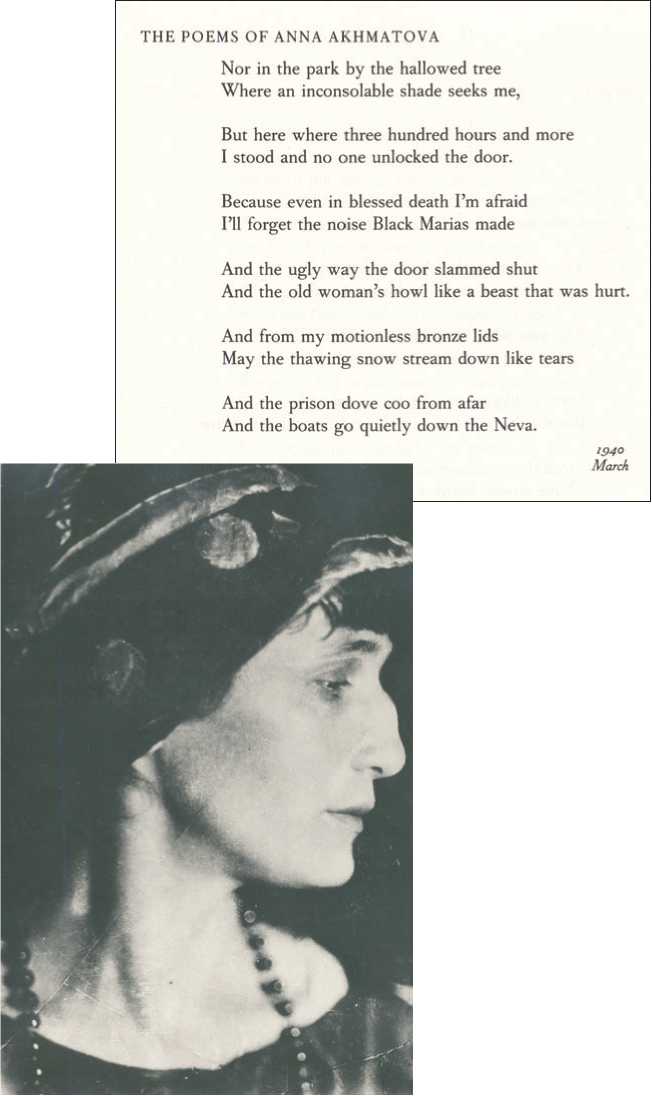

Photograph of poet Anna Akhmatova and family, including repressed son (Lev) as a boy.

On the basis of the decision by the KGB of August 24, 1955, an instruction was issued that local KGB offices tell relatives of those sentenced to death that they were sentenced to ten years and died in captivity. In necessary cases, the death can be registered and a death certificate issued.2

The new KGB procedure meant that death certificates had to be issued with a false date of death. To perpetuate the lie that relatives had not been executed but had died in prison meant that dates of death had to be moved. Serov's memo gives an example of a death that was officially moved to 1942:

(above) Anna Akhmatova's Requiem (English translation), describing her efforts to learn the fate of her repressed son.

(left) Portrait photograph of Anna Akhmatova.

As to the inquiry of N. P. Novak, submitted to the KGB office of Denpro-

Petrovsk on December 24, 1955, she received within ten days confirmation of the death certificate of P P. Novak for January 21, 1942.

World History

World History