The Middle Colonists also possessed traits that later would be seen as distinctly “American.” Their ethnic and religious heterogeneity is a case in point. In the 1640s, when New Amsterdam was only a village, one visitor claimed to have heard eighteen languages spoken there. Traveling through Pennsylvania a century later, the Swedish botanist Peter Kalm encountered “a very mixed company of different nations and religions.” In addition to “Scots, English, Dutch, Germans, and Irish,” he reported, “there were Roman Catholics, Presbyterians, Quakers, Methodists, Seventh Day men, Moravians, Anabaptists, and one Jew.” In New York City one embattled English resident complained, “Our chiefest unhappiness here is too great a mixture of nations, & English the least part.”

Mary Dyer, a Quaker, was banished from Boston, a puritan colony; she repeatedly returned to challenge the law. In 1660 she was hanged in Boston Common.

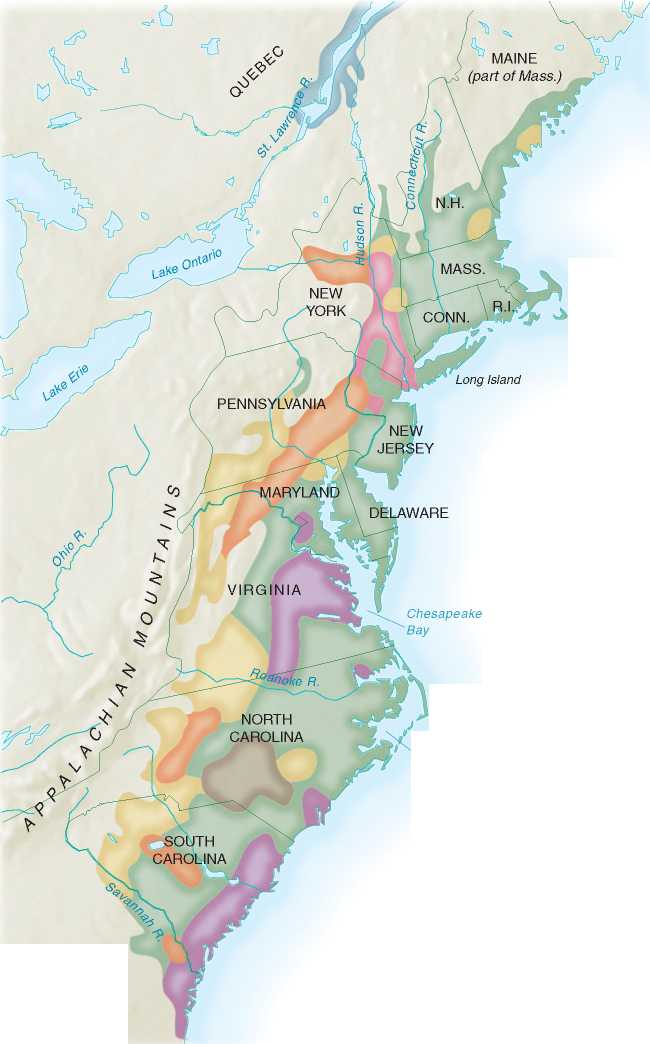

Ethnic Groups of Eastern North America, 1750 Although this chapter retains the historical convention of referring to the coastal Atlantic as "English colonies,” the ethnic composition of the region was much more complicated. To be sure, people of English ancestry predominated in New England, the Chesapeake region, and the Carolinas. But the Hudson River valley remained chiefly Dutch, and southeastern Pennsylvania remained German. Much of the western frontier was populated by English-speaking people of Scottish and Irish ancestry. And in parts of Virginia and the Carolinas, slaves of African descent were in the majority.

Scandinavian and Dutch settlers outnumbered the English in New Jersey and Delaware even after the English took over these colonies. William Penn’s first success in attracting colonists was with German

Quakers and other persecuted religious sects, among them Mennonites and Moravians from the Rhine Valley. The first substantial influx of immigrants into New York after it became a royal colony consisted of French Huguenots. Immigrants more readily risked the dangers of migration when the alternative to remaining in Europe was persecution.

Early in the eighteenth century, hordes of Scots-Irish settlers from northern Ireland and Scotland descended on Pennsylvania. These colonists spoke English but felt little loyalty to the English government, which had treated them badly back home, and less to the Anglican Church, since most of them were Presbyterians. Large numbers of them followed the valleys of the Appalachians south into the back country of Virginia and the Carolinas.

Why so few English in the Middle Colonies? Here, again, timing provides the best answer. The English economy was booming. There seemed to be work for all. Migration to North America, while never drying up, slowed to a trickle. The result was colonies in which English settlers were a minority.

The intermingling of ethnic groups gave rise to many prejudices. Benjamin Franklin, though generally complimentary toward Pennsylvania’s hardworking Germans, thought them clannish to a fault. The already cited French traveler Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, while marveling at the adaptive qualities of “this promiscuous breed,” complained that “the Irish. . . love to drink and to quarrel; they are litigious, and soon take to the gun, which is the ruin of everything.” Yet by and large the various types managed to get along with each other successfully enough. Crevecoeur attended a wedding in Pennsylvania where the groom’s grandparents were English and Dutch and one of his uncles had married a Frenchwoman. The groom and his three brothers, Crevecoeur added with some amazement, “now have four wives of different nations.”

World History

World History