How did life in the South change politically, economically, and socially after the Civil War?

What happened to Native Americans as whites settled the West?

What were the experiences of farmers, cowboys, and miners in the West?

How did mining affect the development of the West?

How important was the concept of the frontier to America’s political and diplomatic development?

Fter the Civil War, the South and the West provided enticing opportunities for American inventiveness and entrepreneurship. The two distinctive regions were ripe for development, and each in its own way became like a colonial appendage of the more prosperous Midwest and Northeast. The war-devastated South had to be rebuilt; the sparsely settled trans-Mississippi West beckoned agricultural and commercial development. Entrepreneurs in the North eagerly sought to exploit both undeveloped regions by providing the capital for urbanization and industrialization. This was particularly true of the West, where before 1860 most Americans had viewed the region between the Mississippi River and California as a barren landscape unfit for human habitation or cultivation, an uninviting land suitable only for Indians and animals. Half the state of Texas, for instance, was still not settled at the end of the Civil War. After 1865, however, the federal government encouraged western settlement and economic development. The construction of transcontinental railroads, the military conquest of the Indians, and a generous policy of distributing government-owned lands combined to help lure thousands of

Pioneers and enterprising capitalists westward. Charles Goodnight, a Texas cattle rancher, recalled that “we were adventurers in a great land as fresh and full of the zest of darers.” By 1900, the South and the West had been transformed in ways—for good and for ill—that few could have predicted, and twelve new states were created out of the western territories.

The Myth of the New South

A fresh vision The major prophet of the so-called the New South during the 1880s was Henry W. Grady, editor of the Atlanta Constitution. “The Old South, ” he said, “rested everything on slavery and agriculture, unconscious that these could neither give nor maintain healthy growth. ” The New South, on the other hand, “presents a perfect democracy” of small farms and diversifying industries. The postwar South, Grady believed, held the promise of a real democracy, one no longer run by the planter aristocracy and no longer dependent upon slave labor.

Henry Grady’s compelling vision of a New South, modeled after the North, attracted many supporters who fervently preached the gospel of industrial development. The Confederacy, they reasoned, had lost the war because it had relied too much upon King Cotton—and slavery. In the future, the South must follow the North’s example and diversify its economy by developing an industrial sector to go along with its agricultural emphasis. From that central belief flowed certain corollaries: that a more efficient agriculture would be a foundation for economic growth, that more widespread education, especially vocational training, would promote regional prosperity, and that sectional peace and racial harmony would provide a stable social environment for economic growth.

Economic growth The New South vision of a more diversified economy made a lot of sense, but it was only partially fulfilled. The chief accomplishment of the New South movement was a dramatic expansion of the region’s textile industry, which produced cotton-based bedding and clothing. From 1880 to 1900, the number of cotton mills in the South grew from 161 to 400, the number of mostly white mill workers (among whom women and children outnumbered men) increased fivefold, and the demand for cotton went up eightfold. By 1900, the South had surpassed New England as the largest producer of cotton fabric in the nation.

Tobacco growing and cigarette production also increased significantly. Essential to the rise of the tobacco industry was the Duke family of Durham,

North Carolina. At the end of the Civil War, the story goes, Washington Duke took a barnful of tobacco and, with the help of his two sons, beat it out with hickory sticks, stuffed it into bags, hitched two mules to his wagon, and set out across the state, selling tobacco in small pouches as he went. By 1872 the Dukes had a factory producing 125,000 pounds of tobacco annually, and Washington Duke prepared to settle down and enjoy success.

His son James Buchanan “Buck” Duke wanted even greater success, however. He recognized that the tobacco industry was “half smoke and half ballyhoo,” so he poured large sums into advertising schemes and perfected the mechanized mass production of cigarettes. Duke also undersold competitors in their own markets and cornered the supply of ingredients needed to make cigarettes. Eventually his competitors agreed to join forces, and in 1890 Duke brought most of them into the American Tobacco Company, which controlled nine tenths of the nation’s cigarette production and, by 1904, about three fourths of all tobacco production. In 1911 the Supreme Court ruled that the massive company was in violation of the Sherman AntiTrust Act and ordered it broken up, but by then Duke had found new worlds to conquer, in hydroelectric power and aluminum.

Systematic use of other natural resources helped revitalize the region along the Appalachian Mountain chain from West Virginia to Alabama. Coal production in the South (including West Virginia) grew from 5 million tons in 1875 to 49 million tons by 1900. At the southern end of the mountains, Birmingham, Alabama, sprang up during the 1870s in the shadow of Red Mountain, so named for its iron ore, and boosters soon tagged the steelmaking city the Pittsburgh of the South.

Urban and industrial growth spawned a need for housing, and after 1870 lumbering became a thriving industry in the South. Northern investors bought up vast pine forests throughout the region. By the turn of the century, lumber had surpassed textiles in value. Tree cutting seemed to know no bounds, despite the resulting ecological devastation. In time the cutover southern forests would be saved only by the warm climate, which fostered quick growth of planted trees.

AGRICULTURE OLD AND NEW By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the South fell far short of the diversified economy and racial harmony that Henry Grady and other proponents of the New South had envisioned in the mid-1880s. The South in 1900 remained the least urban, least industrial, least educated, and least prosperous region. The typical southerner was less apt to be tending a textile loom or iron forge than, as the saying went, facing the eastern end of a westbound mule or risking his life

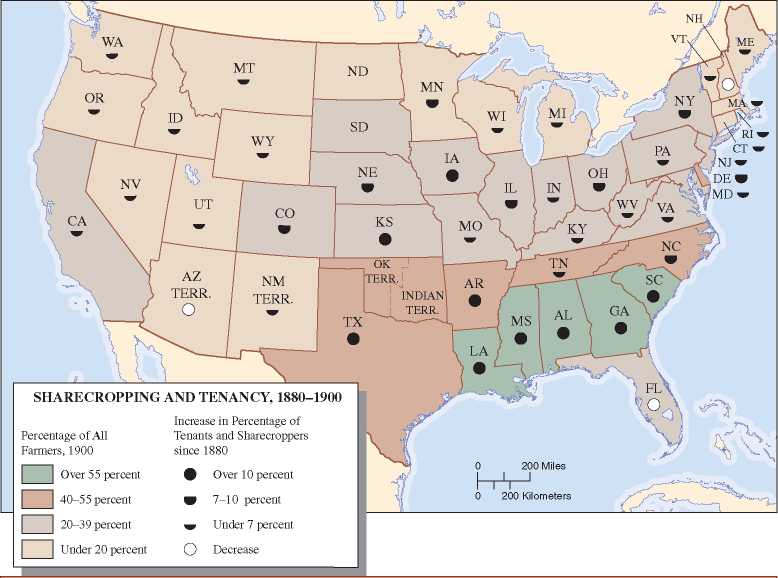

In an Appalachian coal mine. The traditional overplanting of cotton and tobacco fields continued after the Civil War and expanded over new acreage even as its export markets leveled off. The majority of southern farmers were not flourishing. A prolonged deflation in crop prices affected the entire economy during the last third of the nineteenth century. Sagging prices for farm crops made it more difficult than ever to own land. By 1890, low rates of farm ownership in the Deep South belied Henry Grady’s dream of a southern democracy of small landowners: South Carolina, 39 percent; Georgia, 40 percent; Alabama, 42 percent; Mississippi, 38 percent; and Louisiana, 42 percent.

Poverty forced most southern farm workers to give up their hopes of owning land and become sharecroppers or tenants. Sharecroppers, who had

Why was there a dramatic increase in sharecropping and tenancy in the late nineteenth century? Why did the South have more sharecroppers than other parts of the country? Why, in your opinion, was the rate of sharecropping low in the western territories of New Mexico and Arizona?

Nothing to offer the landowner but their labor, worked the owner’s land in return for seed, fertilizer, and supplies and a share of the crop, generally about half. Tenant farmers, hardly better off, might have their own mule, plow, and line of credit with the country store. They were entitled to claim a larger share of the crops. The sharecropper-tenant system was horribly inefficient and corrupting. It was in essence a post-Civil War version of land slavery. Tenants and landowners developed an intense suspicion of each other. Landlords often swindled the farm workers by not giving them their fair share of the crops.

The postwar South suffered from an acute, prolonged shortage of money; people in the former Confederacy had to devise ways to operate without cash. One innovation was the crop-lien system whereby rural merchants furnished supplies to small farm owners in return for liens (or mortgages) on their future crops. Over time the credit offered by the local store coupled with sagging prices for cotton and other crops created a hopeless cycle of perennial debt among farmers. The merchant, who assumed great risks, generally charged interest on borrowed money that ranged, according to one newspaper, “from 24 percent to grand larceny.” The merchant, like the planter (and often the same man), required farmer clients to grow a cash crop, which could be readily sold upon harvesting. This meant that the sharecropping and crop-lien systems warred against agricultural diversity and placed a premium on growing a staple “cash” crop, usually cotton or tobacco. It was a vicious cycle. The more cotton that was grown, the lower the price. If a farmer borrowed $1000 when the price of cotton was 10$ a pound, he had to grow more than 10,000 pounds of cotton to pay back his debt plus interest. If the price of cotton dropped to 5$, he had to grow more than 20,000 pounds just to break even.

The stagnation of rural life thus held millions, white and black, in bondage to privation and ignorance. Eleven percent of whites in the South were illiterate at the end of the nineteenth century, twice the national average. Then as now, poverty accompanied a lack of education. The average annual income of white southerners in 1900 was about half of that of Americans outside the South. Yet the poorest people in the poorest region were the 9 million former slaves and their descendants. Per capita black income was a third of that of southern whites. African Americans also remained the least educated people in the region. The black illiteracy rate in the South in 1900 was nearly 50 percent, almost five times higher than that of whites.

THE REDEEMERS (bOURBONS) In post-Civil War southern politics, centuries-old habits of social deference and political elitism still prevailed. “Every community,” one U. S. Army officer noted in postwar South Carolina, “had its great man, or its little great man, around whom his fellow citizens gather when they want information, and to whose monologues they listen with a respect akin to humility.” After Reconstruction, such “great” men dominated local southern politics, usually because of their ownership of land or their wealth. The supporters of these postwar Democratic leaders referred to them as “redeemers” because they supposedly saved the South from Yankee domination, as well as from the straitjacket of a purely rural economy. The redeemers included a rising class of lawyers, merchants, and entrepreneurs who were eager to promote a more diversified economy based upon industrial development and railroad expansion. The opponents of the redeemers labeled them “Bourbons” in an effort to depict them as reactionaries. Like the French royal family of the same name, which Napoleon had said forgot nothing and learned nothing in the ordeal of the French revolution, the ruling white Bourbons of the postwar South were said to have forgotten nothing and to have learned nothing in the ordeal of the Confederacy and the Civil War. During and after the late 1870s, the Bourbon governors and legislators of the New South slashed state expenditures, including those for the public-school systems started during the Reconstruction era immediately after the war.

Perhaps the ultimate paradox of the Bourbons’ rule was that these champions of white supremacy tolerated a lingering black voice in politics and showed no haste to raise the barriers of racial segregation in public places. In the 1880s, southern politics remained surprisingly open and democratic, with 64 percent of eligible voters, blacks and whites, participating in elections. African Americans sat in the state legislature of South Carolina until 1900 and in the state legislature of Georgia until 1908; some of them were Democrats. The South sent African American congressmen to Washington, D. C., in every election except one until 1900, though they always represented gerrymandered districts in which most of the state’s African American voters had been placed. Under the Bourbons the disenfranchisement of African American voters remained inconsistent, a local matter brought about mainly by fraud and intimidation, but it occurred often enough to ensure white control of the southern states.

A similar flexibility applied to other aspects of race relations. The color line was drawn less strictly immediately after the Civil War than it would be in the twentieth century. In some places, to be sure, racial segregation appeared before the end of Reconstruction, especially in schools, churches, hotels, and rooming houses and in private social relations. In places of public accommodation such as trains, depots, theaters, and diners, discrimination was more sporadic.

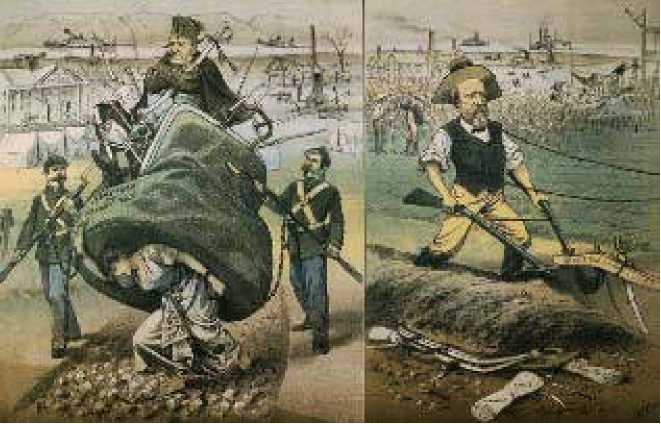

The effects of Radical and Bourbon rule in the South

This 1880 cartoon shows the South staggering under the oppressive weight of military Reconstruction (left) and flourishing under the “Let ’Em Alone Policy” of President Rutherford B. Hayes and the Bourbons (right).

The ultimate achievement of the New South promoters and their allies, the Bourbons, was that they reconciled tradition with innovation. By promoting the growth of industry, the Bourbons led the South into a new economic era, but without sacrificing a mythic reverence for the Old South. Bourbon rule left a permanent mark on the South’s politics, economics, and race relations.

The New West

Like the South, the West is a region wrapped in myths and stereotypes. The vast land west of the Mississippi River contains remarkable geographic extremes: majestic mountains, roaring rivers, searing deserts, sprawling grasslands, and dense forests. For vast reaches of western America, the great epics of the Civil War and Reconstruction were remote events hardly touching the lives of the Indians, Mexicans, Asians, trappers, miners, and Mormons scattered through the plains and mountains. There the march of settlement and exploitation continued, propelled by a lust for land and a passion for profit. Between 1870 and 1900, Americans settled more land in the West than had been occupied by all Americans up to 1870. On one level, western settlement beyond the Mississippi River constitutes a colorful drama of determined pioneers and two-fisted gunslingers overcoming all obstacles to secure their vision of freedom and opportunity amid the region’s awesome vastness. The post-Civil War West offered the promise of democratic individualism, economic opportunity, and personal freedom that had long before come to define the American dream. On another level, however, the colonization of the Far West was a tragedy of shortsighted greed and irresponsible behavior, a story of reckless exploitation that scarred the land, decimated its wildlife, and nearly exterminated Native American culture.

In the second tier of trans-Mississippi states—Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska— and in western Minnesota, farmers began spreading across the Great Plains after midcentury. From California, miners moved east through the mountains, drawn by one new strike after another. From Texas, nomadic cowboys migrated northward onto the plains and across the Rocky Mountains, into the Great Basin of Utah. The settlers encountered climates and landscapes markedly different from those they had left behind. The Great Plains were arid, and the scarcity of water and timber rendered useless the familiar trappings of the pioneer: the ax, the log cabin, the rail fence, and the accustomed methods of tilling the soil. For a long time the region had been called the Great American Desert, unfit for human habitation and therefore, to white Americans, the perfect refuge for Indians. But that view changed in the last half of the nineteenth century as a result of newly discovered deposits of gold, silver, and other minerals, the completion of the transcontinental railroads, the destruction of the buffalo, the collapse of Indian resistance, the rise of the range-cattle industry, and the dawning realization that the arid region need not be a sterile desert. With the use of what water was available, new techniques of dry farming and irrigation could make the land fruitful after all.

THE MIGRATORY STREAM During the second half of the nineteenth century, an unrelenting stream of migrants flowed into the largely Indian and Hispanic West. Millions of Anglo-Americans, African Americans, Mexicans, and European and Chinese immigrants transformed the patterns of western society and culture. Most of the settlers were relatively prosperous white, native-born farm folk. Because of the expense of transportation, land, and supplies, the very poor could not afford to relocate. Three quarters of the western migrants were men.

The largest number of foreign immigrants came from northern Europe and Canada. In the northern plains, Germans, Scandinavians, and Irish were especially numerous. In the new state of Nebraska in 1870, a quarter of the 123,000 residents were foreign-born. In North Dakota in 1890, 45 percent of the residents were immigrants. Compared with European immigrants, those from China and Mexico were much less numerous but nonetheless significant. More than 200,000 Chinese arrived in California between 1876 and 1890.

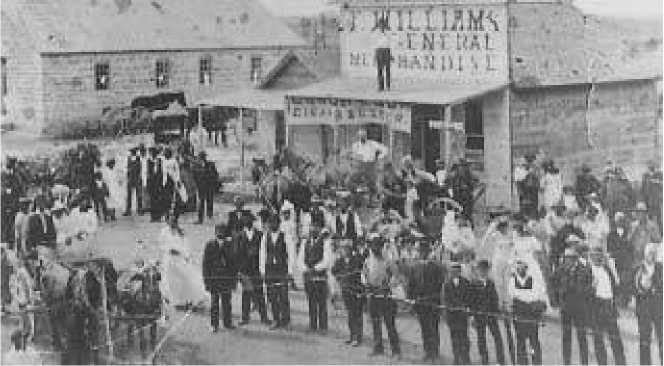

AFRICAN AMERICAN MIGRATION In the aftermath of the collapse of Radical Republican rule in the South, thousands of African Americans began migrating west from Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Texas. Some six thousand southern blacks arrived in Kansas in 1879, and as many as twenty thousand followed the next year. These African American migrants came to be known as Exodusters, because they were making their exodus from the South—in search of a haven from racism and poverty. The exodus of black southerners to the West died out by the early 1880s. Many of the settlers were unprepared for the living conditions on the plains. Their Kansas homesteads were not large enough to be self-sustaining, and most of the black farmers were forced to supplement their income by hiring themselves out to white ranchers. Drought, grasshoppers, prairie fires, and dust storms led to crop failures. The sudden influx of so many people taxed resources and patience. Many of the African American pioneers in Kansas soon abandoned their land and moved to the few cities in the state.

Nicodemus, Kansas

A colony founded by southern blacks in the 1860s.

Life on the frontier was not the “promised land” that settlers had been led to expect. Nonetheless, by 1890 some 520,000 African Americans lived west of the Mississippi River. As many as 25 percent of the cowboys who participated in the Texas cattle drives were African Americans.

MINING THE WEST Valuable mineral deposits continued to lure people to the West after the Civil War. The California miners of 1849 (forty-niners) set the typical pattern, in which the sudden, disorderly rush of prospectors to a new find was quickly joined by camp followers—a motley crew of peddlers, saloon keepers, prostitutes, cardsharps, hustlers, and assorted desperadoes eager to mine the miners. If a new field panned out, the forces of respectability and more subtle forms of exploitation slowly worked their way in. Lawlessness gave way to vigilante rule and, finally, to a stable community.

The drama of the 1849 gold rush was reenacted time and again in the following three decades. Along the South Platte River, not far from Pikes Peak in Colorado, a prospecting party found gold in 1858, and stories of success brought perhaps one hundred thousand “fifty-niners” into the country by the next year. New discoveries in Colorado kept occurring: near Central City in 1859, at Leadville in the 1870s, and the last important strikes in the West, again gold and silver, at Cripple Creek in 1891 and 1894. During those years, farming and grazing had given the economy a stable base, and Colorado, the Centennial State, entered the union in 1876.

While the early miners were crowding around Pikes Peak, the Comstock Lode was discovered near Gold Hill, Nevada. H. T. P. Comstock, a Canadian-born fur trapper, had drifted to the Carson River diggings, which opened in 1856. He talked his way into a share in a new discovery made by two other prospectors in 1859 and gave it his own name. The lode produced gold and silver. Within twenty years, it had yielded more than $300 million from shafts that reached hundreds of feet into the mountainside. In 1861, largely on account of the settlers attracted to the Comstock Lode, Nevada became a territory, and in 1864 the state of Nevada was admitted to the Union in time to give two electoral votes to Abraham Lincoln (the new state’s third electoral voter got caught in a snowstorm).

The growing demand for orderly government in the West led to the hasty creation of new territories and eventually the admission of a host of new states. After Colorado’s admission in 1876, however, there was a long hiatus because of party divisions in Congress: Democrats were reluctant to create states out of territories that were heavily Republican. After the sweeping Republican victory in the 1888 legislative races, however, Congress admitted

The Dakotas, Montana, and Washington in 1889 and Idaho and Wyoming in 1890. Utah entered the Union in 1896 (after the Mormons abandoned the practice of polygamy) and Oklahoma in 1907, and in 1912 Arizona and New Mexico rounded out the forty-eight contiguous states.

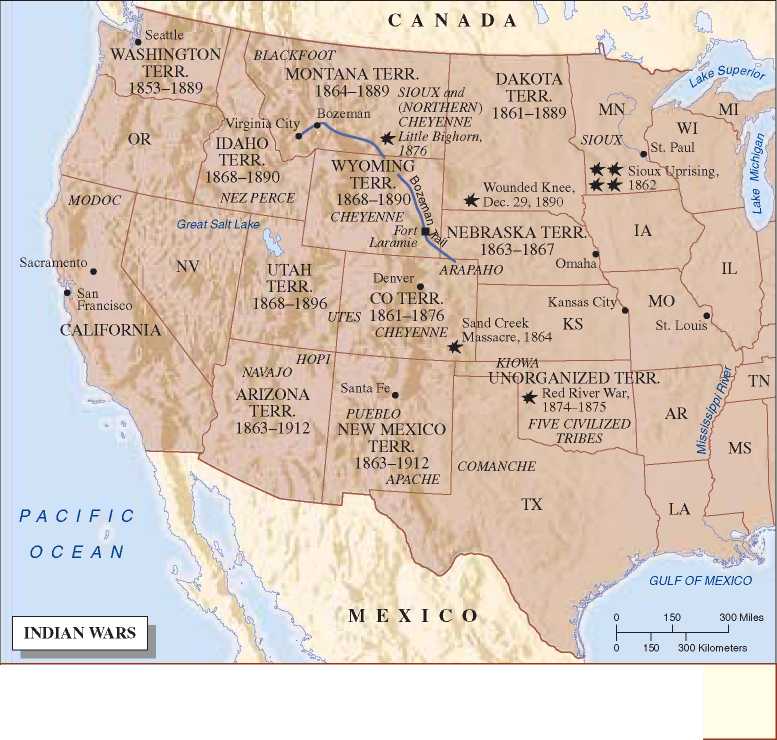

THE INDIAN WARS As the frontier pressed in from east and west, some 250,000 Native Americans were forced into what was supposed to be their last refuge, the Great Plains and in the mountain regions of the Far West. The 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty, in which the chiefs of the Plains tribes agreed to accept definite tribal borders and allow white emigrants to travel on their trails unmolested, worked for a while, with wagon trains passing safely through Indian lands and the army building roads and forts without resistance. Fighting resumed, however, as the emigrants began to encroach upon Indian lands on the plains rather than merely pass through them.

From the early 1860s until the late 1870s, the frontier raged with Indian wars. In 1864, Colorado’s governor persuaded most of the warring Indians in his territory to gather at Fort Lyon, on Sand Creek, where they were promised protection. Despite that promise, Colonel John M. Chivington’s untrained militia attacked an Indian camp flying a white flag of truce, slaughtering two hundred peaceful Indians—men, women, and children—in what one general called the “foulest and most unjustifiable crime in the annals of America.”

With other scattered battles erupting, a congressional committee in 1865 gathered evidence on the grisly Indian wars and massacres. Its 1867 “Report on the Condition of the Indian Tribes” led to the creation of an Indian Peace Commission charged with removing the causes of the Indian wars. Congress decided that this would be best accomplished at the expense of the Indians, by persuading them to take up life on out-of-the-way reservations. Yet the persistent encroachment of whites on Indian hunting grounds continued. In 1870, Indians outnumbered whites in the Dakota Territory by two to one; in 1880, whites outnumbered Indians by more than six to one.

In 1867, a conference at Medicine Lodge, Kansas, ended with the Kiowas, Comanches, Arapahos, and Cheyennes reluctantly accepting land in western Oklahoma. The following spring the Sioux agreed to settle within the Black Hills Reservation in Dakota Territory. But Indian resistance in the southern plains continued until the Red River War of 1874-1875, when General Philip Sheridan forced the Indians to disband in the spring of 1875. Seventy-two Indian chiefs were imprisoned for three years.

Meanwhile, trouble was brewing again in the north. In 1874, Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer, a reckless, glory-seeking officer, led an exploratory expedition into the Black Hills. Miners were soon filtering onto the Sioux

The Battle of Little Bighorn, 1876

A painting by Amos Bad Heart Bull, an Oglala Sioux.

Hunting grounds despite promises that the army would keep them out. The army had done little to protect Indian land, but when ordered to move against wandering bands of Sioux hunting on the range according to their treaty rights, it moved vigorously.

What became the Great Sioux War was the largest military event since the end of the Civil War and one of the largest campaigns against Indians in American history. The war lasted fifteen months and entailed fifteen battles in present-day Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, and Nebraska. The heroic chief Sitting Bull ably led the Sioux. In 1876, after several indecisive encounters, Custer found the main encampment of Sioux and their Northern Cheyenne allies on the Little Bighorn River. Separated from the main body of soldiers and surrounded by 2,500 warriors, Custer’s detachment of 210 men was annihilated.

Instead of following up their victory, the Indians celebrated and renewed their hunting. The army quickly regained the offensive and compelled the Sioux to give up their hunting grounds and goldfields in return for payments. Forced onto reservations situated on the least valuable land in the region, the Indians soon found themselves struggling to subsist under harsh conditions. Many of them died of starvation or disease. When a peace commission imposed a settlement, Chief Spotted Tail said: “Tell your people that since the Great Father promised that we should never be removed, we have

Been moved five times. . . . I think you had better put the Indians on wheels and you can run them about wherever you wish.”

In the Rocky Mountains and to the west, the same story of hopeless resistance was repeated. Indians were the last obstacle to white western expansion, and they suffered as a result. The Blackfeet and Crows had to leave their homes in Montana. In a war along the California-Oregon boundary, the Modocs held out for six months in 1871-1872 before they were overwhelmed. In 1879 the Utes were forced to give up their vast territories in western Colorado. In Idaho the peaceful Nez Perce bands refused to surrender land along the Salmon River, and prolonged fighting erupted there and

What was the Great Sioux War? What happened at Little Bighorn, and what were the consequences? Why were hundreds of Indians killed at Wounded Knee?

In eastern Oregon. Joseph, one of several Nez Perce chiefs, delivered an eloquent speech of surrender that served as an epitaph to the Indians’ efforts to withstand the march of American empire: “I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs

Are killed____The old men are all dead____I want to have time to look for my

Children, and see how many of them I can find. . . . Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.”

A generation of Indian wars virtually ended in 1886 with the capture of Geronimo, a chief of the Chiricahua Apaches, who had fought white settlers in the Southwest for fifteen years. But there would be a tragic epilogue. Late in 1888, Wovoka (or Jack Wilson), a Paiute in western Nevada, fell ill and in a delirium imagined he had visited the spirit world, where he learned of a deliverer coming to rescue the Indians and restore their lands. To hasten their deliverance, he said, the Indians must take up a ceremonial dance at each new moon. The Ghost Dance craze fed upon old legends of a coming messiah and spread rapidly. In 1890 the Lakota Sioux adopted it with such fervor that it alarmed white authorities. They banned the Ghost Dance on Lakota reservations, but the Indians defied the order and a crisis erupted. On December 29, 1890, a bloodbath occurred at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. An accidental rifle discharge led nervous soldiers to fire into a group of Indians who had come to surrender. Nearly two hundred Indians and twenty-five soldiers died in the Battle of Wounded Knee. The Indian wars had ended with characteristic brutality and misunderstanding. General Philip Sheridan was acidly candid in summarizing how whites had treated the Indians: “We took away their country and their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease and decay and among them, and it was for this and against this that they made war. Could anyone expect less?”

INDIAN POLICY The slaughter of buffalo and Indians ignited widespread criticism. Politicians and religious leaders castigated the persistent mistreatment of Indians. In his annual message of 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes joined the protest: “Many, if not most, of our Indian wars have had their origin in broken promises and acts of injustice on our part.” Helen Hunt Jackson, a novelist and poet, focused attention on the Indian cause in A Century of Dishonor (1881). Its impact on American attitudes toward the Indians was comparable to the effect that Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) had on the abolitionist movement before the Civil War. U. S. policies regarding Indians gradually became more benevolent, but this change did little to ease the plight of the Indians and actually helped destroy the remnants of their culture. The reservation policy inaugurated by the Peace Commission in 1867 did little more than extend a practice that dated from colonial Virginia. Partly humanitarian in motive, it also saved money: housing and feeding Indians on reservations cost less than fighting them.

Well-intentioned reformers sought to “Americanize” Indians by dealing with them as individuals rather than tribes. The fruition of such reform efforts came with the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887. Sponsored by Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, the act divided tribal lands, granting 160 acres to each head of a family and lesser amounts to others. But the more it changed, the more Indian policy remained the same. Between 1887 and 1934, Indians lost an estimated 86 million of their 130 million acres. Most of what remained was unsuited for agriculture.

CATTLE AND COWBOYS While the West was being taken from the Indians, cattle entered the grasslands where the buffalo had roamed. For many years, wild cattle competed with the buffalo in the Spanish borderlands. Interbreeding with Anglo-American cattle produced the Texas longhorns: lean and rangy, they were noted more for speed and endurance than for yielding a choice steak. They had little value, moreover, because the largest markets for beef were too far away. New opportunities arose after the Civil War as railroads pushed farther west, where cattle could be driven through relatively vacant lands. Joseph G. McCoy, an Illinois livestock dealer, recognized the possibilities of moving the cattle trade west. In 1867 in Abilene, Kansas, he bought 250 acres for a stockyard; he then built a barn, an office building, livestock scales, a hotel, and a bank. He then sent an agent into Indian-owned areas to recruit owners of herds bound north to go through Abilene. Over the next few years, Abilene flourished as the first successful Kansas cowtown. The ability to ship huge numbers of western cattle by rail transformed ranching into a major industry.

The thriving cattle industry spurred rapid growth. The population of Kansas increased from 107,000 in 1860 to 365,000 ten years later and reached almost 1 million by 1880. Nebraska witnessed similar increases. The flush times of the cowtown soon passed, however, and the long cattle drives played out too, because they were economically unsound. The dangers of the trail, the wear and tear on men and cattle, the charges levied on drives across Indian territory, and the advance of farms across the trails combined to persuade cattlemen that they could function best near railroads. As railroads

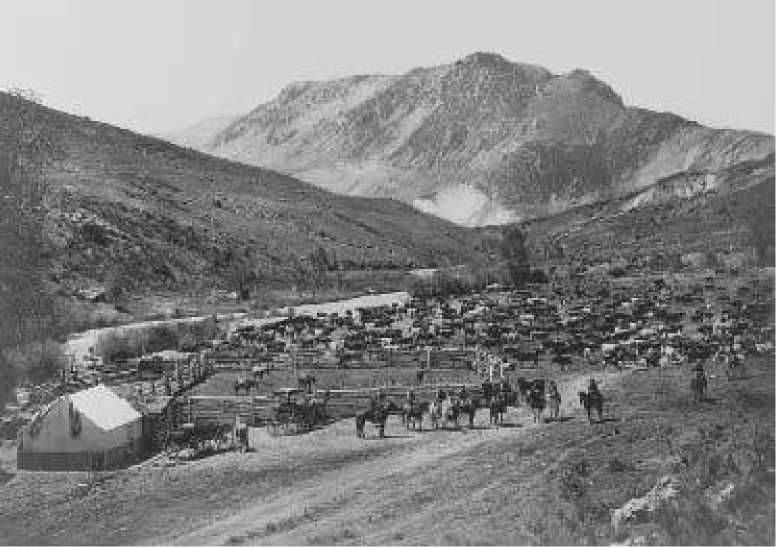

The cowboy era

Cowboys herd cattle near Cimarron, Colorado, 1905.

Spread out into Texas and across the plains, the cattle business spread with them over the High Plains as far as Montana and on into Canada.

In the absence of laws governing the open range, cattle ranchers at first worked out a code of behavior largely dictated by circumstances. As cattle often wandered onto other ranchers’ claims, cowboys would “ride the line” to keep the animals off the adjoining ranches. In the spring they would “round up” the herds, which invariably got mixed up, and sort out ownership by identifying the distinctive ranch symbols “branded,” or burned, into the cattle. All that changed in 1873, when Joseph Glidden, an Illinois farmer, invented the first effective barbed wire, which ranchers used to fence off their claims at relatively low cost. Ranchers rushed to buy the new wire fencing, and soon the open range was no more. Cattle raising, like mining, evolved from a romantic adventure into a big business dominated by giant enterprises.

FARMERS AND THE LAND Farming has always been a hard life, and it was made more so on the Great Plains by the region’s unforgiving environment and mercurial weather. After 1865, on paper at least, the federal land laws offered farmers favorable terms. Under the Homestead Act of 1862, a settler (“homesteader”) could gain title to federal land simply by staking out a claim and living on it for five years, or he could buy land at $1.25 an acre after six months. But such land legislation was predicated upon the tradition of farming the fertile lands east of the Mississippi River, and the laws were never adjusted to the fact that much of the prairie was suited only for cattle raising. Cattle ranchers were forced to obtain land by gradual acquisition from homesteaders or land-grant railroads.

The first arrivals on the sod-house frontier faced a grim struggle against danger, adversity, and monotony. Though land was relatively cheap, horses, livestock, wagons, wells, lumber, fencing, seed, and fertilizer were not. Freight rates and interest rates on loans seemed criminally high. As in the South, declining crop prices produced chronic indebtedness, leading strapped western farmers to embrace virtually any plan to inflate the money supply. The virgin land itself, although fertile, resisted planting; the heavy sod broke many a plow. Since wood was almost nonexistent on the prairie, pioneer families used buffalo chips (dried dung) for fuel.

Farmers and their families also fought a constant battle with the elements: tornadoes, hailstorms, droughts, prairie fires, blizzards, and pests. Swarms of locusts often clouded the horizon, occasionally covering the ground six inches deep. A Wichita newspaper reported in 1878 that the grasshoppers devoured “everything green, stripping the foliage off the bark and from the tender twigs of the fruit trees, destroying every plant that is good for food or pleasant to the eyes, that man has planted.”

As the railroads brought piles of lumber from the East, farmers could leave their sod houses (homes built of sod) to build more comfortable frame dwellings. New machinery helped provide fresh opportunities. In 1868, James Oliver, a Scottish immigrant living in Indiana, made a successful chilled-iron plow. This “sodbuster” plow greatly eased the task of breaking the tough grass roots of the plains. Improvements and new inventions in threshing machines, hay mowers, planters, manure spreaders, cream separators, and other devices lightened the burden of farm labor but added to the farmers’ capital outlay. In Minnesota, the Dakotas, and central California the gigantic “bonanza farms,” with machinery for mass production, became the marvels of the age. On one farm in North Dakota, 13,000 acres of wheat made a single field. Another bonanza farm employed over 1,000 migrant workers to tend 34,000 acres.

While the overall value of farmland and farm products increased in the late nineteenth century, small farmers did not keep up with the march of progress. Their numbers grew in size but decreased in proportion to the population at large. Wheat in the Western states, like cotton in the antebellum South, was the great export crop that spurred economic growth. For a variety of reasons, however, few small farmers prospered. By the 1890s they were in open revolt against the “system” of corrupt processors (middlemen) and “greedy” bankers who they believed conspired against them.

PIONEER WOMEN The West remained a largely male society throughout the nineteenth century. Women were not only a numerical minority; they also continued to face traditional legal barriers and social prejudice. A wife could not sell property without her husband’s approval, for example. Texas women could not sue except for divorce, nor could they serve on juries, act as lawyers, or witness a will. But the fight for survival in the trans-Mississippi West made men and women more equal partners than in the East. Many women who lost their mates to the deadly toil of sod busting thereafter assumed complete responsibility for their farms. In general, women on the prairie became more independent than women leading domestic lives back East. A Kansas woman explained “that the environment was such as to bring out and develop the dominant qualities of individual

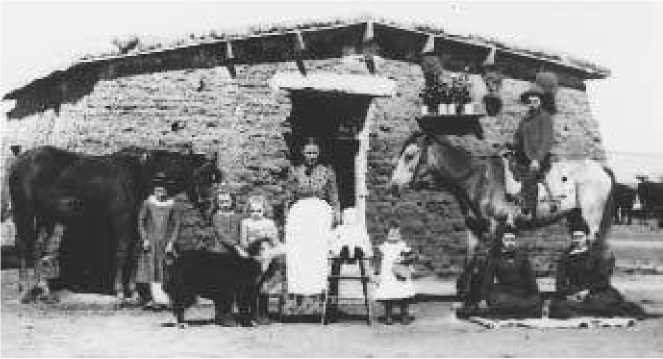

Women of the frontier

A woman and her family in front of their sod house. The difficult life on the prairie led to more egalitarian marriages than were found in other regions of the country.

Character. Kansas women of that day learned at an early age to depend on themselves—to do whatever work there was to be done, and to face danger when it must be faced, as calmly as they were able.”

THE END OF THE FRONTIER American life reached an important juncture at the end of the nineteenth century. The 1890 national census reported that the frontier era in American development was over; people by then had spread across the entire continent. This fact inspired the historian Frederick Jackson Turner to develop his influential frontier thesis, first outlined in “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” a paper delivered to the American Historical Association in 1893. “The existence of an area of free land,” Turner wrote, “its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.” The frontier, he added, had shaped the national character in fundamental ways. It was

To the frontier [that] the American intellect owes its striking characteristics. That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and acquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom—these are traits of the frontier, or traits called out elsewhere because of the existence of the frontier.

In 1893, Turner concluded, “four centuries from the discovery of America, at the end of a hundred years under the Constitution, the frontier has gone and with its going has closed the first period of American history.”

Turner’s “frontier thesis” guided several generations of scholars and students in their understanding of the distinctive characteristics of American history. His view of the frontier as the westward-moving source of the nation’s democratic politics, open society, unfettered economy, and rugged individualism, far removed from the corruptions of urban life, gripped the popular imagination as well. But it left out much of the story. The frontier experience Turner described exaggerated the homogenizing effect of the frontier environment and virtually ignored the role of women, African Americans, Native Americans, Mormons, Hispanics, and Asians in shaping the diverse human geography of the western United States. Turner also implied that the West would be fundamentally different after 1890 because the frontier experience was essentially over. But in many respects that region has retained the qualities associated with the rush for land, gold, timber, and water rights during the post-Civil War decades. The mining frontier, as one historian has recently written, “set a mood that has never disappeared from the West: the attitude of extractive industry—get in, get rich, get out.”

World History

World History