Much of the interior design was undertaken in Belfast, Liverpool and London by the firm of Aldam Heaton, whose senior designer was Edward Croft-Smith. The firm had worked on earlier White Star liners, as well as on the Ismay family houses, but under pressure of time, much of the work was taken over by Harland & Wolff’s own in-house decorators, who evolved a mixture of styles suitable to Edwardian fashion and taste—essentially rather heavy versions of multiple styles from Renaissance to Modern Dutch.

In addition to designers and decorators, cabinet-makers and wood-carvers were either employed or subcontracted by Harland & Wolff. Samuel Leith was responsible for tables, cupboards and cabinets, while carvers such as Leonard Waldron and Charles Wilson were employed to decorate wood finishings. Wilson made the clock surround, Honor and Glory Crowning Time, for the first-class main staircase on Olympic, and carved a similar piece for Titanic. When Titanic sailed, her final fittings were still so behind that the clock for this piece hadn’t yet been delivered, and a mirror had to be substituted pro tem.

Woodcarvings were naturally at their most ornate (modern taste would find them oppressive) in first class; in second class they were simpler and more repetitive, and in third class simpler still, yet 186 woodcarvers alone were employed on Olympic, and the same number would have been required for Titanic. Harland & Wolff had its own artists’ and decorators’ studio, which was responsible for panelwork, etched glass, and even curtain and carpet design, though some of this was subcontracted. Suitable genre paintings were commissioned for the first - and second-class public rooms. As in any great structure, land-based or ocean-going, every last detail needed attention—from

A photograph taken by Robert Welch in 1899 showing the newly refurbished painters' studio, where the Harland & Wolff artists are working on embossed panels for the interior decoration of a liner.

Doorknobs to lavatory pedestals, from upholstery to napkins. Belfast’s linen industry did well from the napery and bedlinen departments. Olympic carried over 190,000 items of linenware and we can assume similar numbers for Titanic.

Carpets, cushions and other soft furnishings needed to be hard-wearing, high quality, and patterned so as not to show use. That rule still applies in any decent liner or good hotel today.

Getting the ship ready was a race against time and rivals. The German Imperator (see page 61), which was snapping at the heels of the Olympic class, had public rooms designed by Charles Mewes, the architect of the Ritz Hotel in Paris, which would make those of the Olympic class look almost cramped. Meanwhile, Cunard was already working on the four-funneled Aquitania (45,647 gross tons weight, with a beam of 97 feet and length of 901 feet, driven by Parsons’ turbines and capable of a top speed of 24 knots), which was built by John Brown. Designed by Cunard’s chief ship’s architect Leonard Peskett, who had traveled on Olympic and made copious notes, she was launched on April 21, 1913, just over a year after the wreck of Titanic, took her maiden voyage on May 30 in the following year, and stayed in service

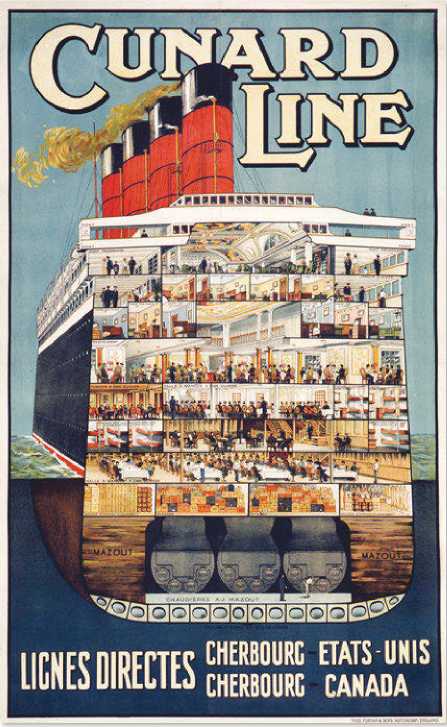

A French poster advertising the RMS Aquitania, showing the delights of her interior. Aquitania was among the first ships to carry enough lifeboats for all passengers and crew, and she was the first Cunarder for which luxury was a higher priority than speed.

Until she was scrapped in 1950. Aquitania was a real twentieth-century heroine, enjoying a thirty-six-year career (including war service), during which she carried 1.2 million passengers over 3 million miles on 450 voyages. Her faultless decor (designed by Mewes’s business partner Arthur Davis, who tended towards the Palladian) earned her the sobriquet “The Ship Beautiful.”

The intricate decoration of ships by real craftsmen—now a dying tradition, as witness the overblown suburban design of most modern liners and cruise ships— went back a long way. The form of a ship, designed to be buoyant, is in itself an aesthetic pleasure. When there was no straight-down stem but a proper prow, a figurehead adorned all important ships.

Astern, the cabin lights were usually beautifully decorated as well. As with other functional and fairly prosaic machines,

Such as guns, our ancestors lavished decoration of the finest sort on their ships. But that was in the days of wood. As iron, steel and steam replaced wood and sail, exterior decoration was lost, but the art of decoration was alive and well on the inside. In fact, you could say that decoration moved from the outside in, since few wooden sailing ships had anything but purely functional interiors, apart perhaps from the captain’s cabin.

When Olympic was scrapped in 1935, it wasn’t because she was worn out, unseaworthy or unreliable. It was because her passenger layout was old-fashioned and modern passengers wanted, for example, more privacy and more en-suite bathrooms. We have to make some mental jumps here because what we now think of as standard, even in a modest hotel, would have been considered the last word in luxury a hundred years ago.

An en-suite bathroom is one example, but it goes further than that. Even in first-class accommodation, many cabins were double-berthed, and that could mean (if you were traveling alone) having to share with a stranger. No hotel on land would offer such facilities to the rich or expect them to be accepted, but it was not unusual a hundred years ago on a liner. However, given the fact that once aboard there would be no escape for five days or so if on the transatlantic run, a lot of effort was put into the public rooms. But even these were somewhat restricted, most being only as high as the deck they were on, though the reception areas around the grand staircases were higher and surmounted by glass domes, as was the style in Parisian art nouveau brasseries, such as the Bofinger.

But that apart, by 1911 ocean liners in most respects outstripped all but the most luxurious hotels, and were not bettered even by them. To be sure, third-class accommodation was plain and simple, but the facilities offered—electricity, hot running water, flush lavatories— were better than those third-class passengers would have known at home; second class had evolved into something far ahead of what it had been in the late nineteenth century, and again facilities here were probably better than those at home for many passengers.

World History

World History