Momentous events in Europe influenced the situation. In 1789 the French Revolution erupted, and four years later war broke out between France and Great Britain and most of the rest of Europe. With France fighting Great Britain and Spain, there arose the question of America’s obligations under the Alliance of 1778. That treaty required the United States to defend the French West Indies “forever against all other powers.” Suppose the British attacked the French island of Martinique; must America declare war on Britain? Legally the United States was so obligated, but no responsible American statesman urged such a policy. With the British in Canada and Spanish forces to the west and south, the nation would be in serious danger if it entered the war. Instead, in April 1793, Washington issued a proclamation of neutrality committing the United States to be “friendly and impartial” toward both sides in the war.

I : ’ 'ti.

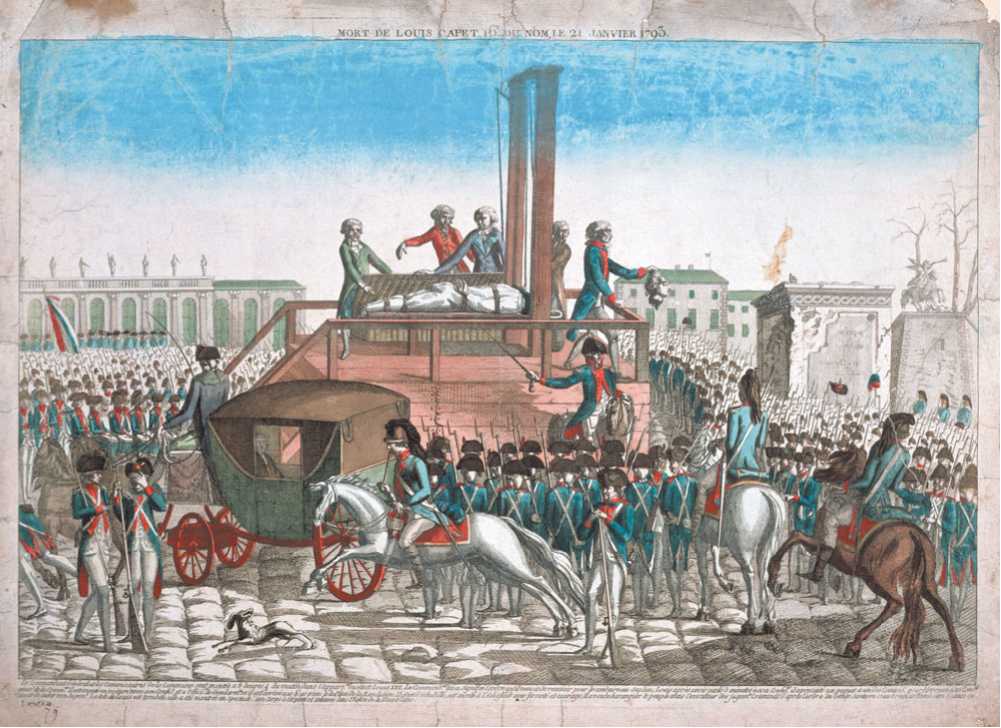

King Louis XVI of France is beheaded in Paris, January 21,1793. Alexander Hamilton recommended termination of the nation's alliance with France. Thomas Jefferson argued that the treaty should be preserved because it had been made with the French people and not the monarch. As the French Revolution became still bloodier, American enthusiasm for the French radicals, and for radicalism in general, began to wane.

In the summer of 1793, a yellow fever epidemic struck Philadelphia, killing nearly 4,000. Tens of thousands fled the city, including President Washington and much of the federal government.

Absalom Jones, a religious leader, was among the free blacks who remained to take care of the sick and the dead. This portrait of Jones is by Raphaelle Peale.

Meanwhile the French had sent a special representative, Edmond Charles Genet, to the United States to seek support. During its early stages, especially when France declared itself a republic in 1792, the revolution had excited much enthusiasm in the United States, for it seemed to indicate that American democratic ideas were already engulfing the world. The increasing radicalism in France tended to dampen some of the enthusiasm, yet when “Citizen” Genet landed at Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1793, the majority of Americans probably wished the revolutionaries well. As Genet, a charming, ebullient young man, made his way northward to present his credentials, cheering crowds welcomed him in every town. Quickly concluding that the proclamation of neutrality was “a harmless little pleasantry designed to throw dust in the eyes of the British,” he began, in plain violation of American law, to license American vessels to operate as privateers against British shipping and to grant French military commissions to a number of Americans in order to mount expeditions against Spanish and British possessions in North America.

Washington received Genet coolly, and soon thereafter demanded that he stop his illegal activities. Genet, whose capacity for self-deception was monumental, appealed to public opinion over the president’s head and continued to commission privateers. Even Jefferson was soon exasperated by Genet, whom he described as “hot headed, all imagination, no judgment and even indecent toward the P[resident].” Washington then requested his recall. The incident ended on a ludicrous note. When Genet left France, he had been in the forefront of the Revolution. But events there had marched swiftly leftward, and the new leaders in Paris considered him a dangerous reactionary. His replacement arrived in America with an order for his arrest. To return might well mean the guillotine, so Genet asked the government that was expelling him for political asylum! Washington agreed, for he was not a vindictive man. A few months later the bold revolutionary married the daughter of the governor of New York and settled down as a farmer on Long Island, where he raised a large family and “moved agreeably in society.”

The Genet affair was incidental to a far graver problem. Although the European war increased the foreign demand for American products, it also led to attacks on American shipping by both France and Great Britain. Each power captured American vessels headed for the other’s ports whenever it could. In 1793 and 1794 about 600 United States ships were seized.

The British attacks caused far more damage, both physically and psychologically, because the British fleet was much larger than France’s, and France at least professed to be America’s friend and to favor freedom of trade for neutrals. In addition the British issued secret orders late in 1793 turning their navy loose on neutral ships headed for the French West Indies. Pouncing without warning, British warships captured about 250 American vessels and sent them off as prizes to British ports. The merchant marine, one American diplomat declared angrily, was being “kicked, cuffed, and plundered all over the Ocean.” The attacks roused a storm in America, reviving hatreds that had been smoldering since the Revolution. The continuing presence of British troops in the Northwest (in 1794 the British began to build a new fort in the Ohio country) and the restrictions imposed on American trade with the British West Indies raised tempers still further. To try to avoid a war, for he wisely believed that the United States should not become embroiled in the Anglo-French conflict, Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to London to seek a settlement with the British.

World History

World History