The first concern of the colonial household was the manufacture of food and clothing, and most colonial families had to produce their own. Wheat, rye, or Indian corn grown on the farm was ground into flour at the local gristmill, but the women of the family made plentiful weekly rations of bread and hardtack. Jellies and jams were made with enough sweetening from honey, molasses, or maple syrup to preserve them for indefinite periods in open crocks. The men of the family were rarely teetotalers, and the contracts signed by indentured servants indicate that nearly a third of the feeding costs of indentures was for alcoholic beverages. Beer, rum, and whiskey were easiest to make, but wines, mead, and an assortment of brandies and cordials were specialties of some households.

Making clothing—from preparing the raw fiber to sewing the finished garments—kept the women and children busy. Knit goods such as stockings, mittens, and sweaters were the major items of homemade apparel. Linsey-woolsey (made of flax and wool) and jeans (a combination of wool and cotton) were the standard textiles of the North and of the pioneer West. Equally indestructible, though perhaps a little easier on the skin, was fustian, a blend of cotton and flax used mostly in the South. Dress goods and fine suitings had to be imported from England, and even for the city dweller, the purchase of such luxuries was usually a rare and exciting occasion.

Early Americans who had special talents produced everything from nails and kitchen utensils to exquisite cabinets. Throughout colonial America the men of the family participated in the construction of their own homes, although exacting woodwork and any necessary masonry might be done by a specialist. Such specialists, of widely varying abilities, could be found both in cities and at country crossroads. Urban centers especially exhibited a great variety of skills, even at a rather early date. In 1697, for example, 51 manufacturing handicrafts, in addition to the building trades, were represented in Philadelphia.

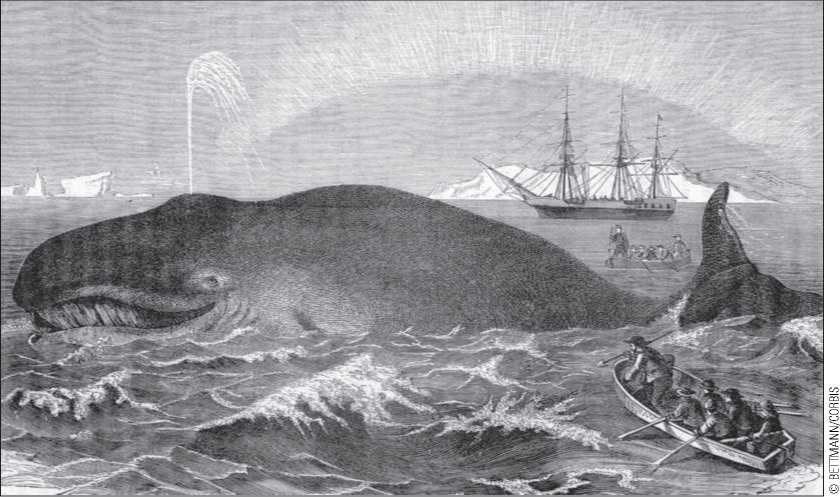

Whaling was a hazardous but profitable industry in early America and an important part of New England’s seafaring tradition. New Bedford, where Captain Ahab started his quest for Moby Dick, and Nantucket were the main whaling centers of New England.

The distinction between the specialized craftsman and the household worker, however, was not always clear in colonial America. Skilled slaves on southern plantations might devote all their time to manufacture; this made them artisans, even though their output was considered a part of the household. On the other hand, the itinerant jack-of-all-trades, who moved from village to village selling reasonably expert services, was certainly not a skilled craftsman in the European sense. Because of the scarcity of skilled labor, individual workers often performed functions more varied than they would have undertaken in their native countries; a colonial tanner, for example, might also be a currier (leather preparer) and a shoemaker. Furthermore, because of the small local markets and consequent geographic dispersal of nearly all types of production, few workers in the same trade were united in any particular locality.

For this reason, few guilds or associations of craftsmen of the same skill were formed. As an exception, however, we note that as early as 1648, enough shoemakers worked in Boston to enable the General Court to incorporate them as a guild, and by 1718, tailors and cordwainers were so numerous in Philadelphia that they, too, applied for incorporation (Bridenbaugh 1971).

World History

World History