At the same time that manufacturers were becoming bigger and more engaged in direct distribution, retailing was also undergoing a revolution. As cities became bigger and

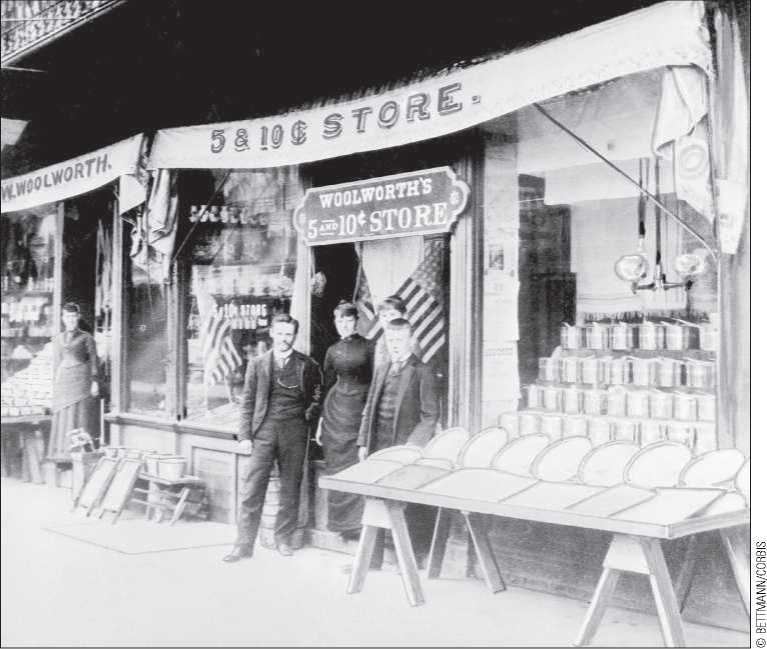

F. W. Woolworth—a pioneer in chain-store merchandising—opened his first store in 1879 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. At today’s prices, it would be a one and two dollar store.

More congested, the convenience of being able to shop for all personal necessities in a single store had an increasing appeal. The response was the department store. At first, department stores bought merchandise through wholesalers. However, larger stores such as Macy’s in New York, John Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia, and Marshall Field’s in Chicago took advantage of their growing size to obtain price reductions by going directly to manufacturers or their agents. Because of the size of their operations, large stores with numerous clerks had to set one price for all customers, and the old practice of haggling with merchants over the price of an article was soon a thing of the past. So successful was the department store concept that, by 1920, even small cities could usually boast one.

Smaller, specialized retail outlets, operating on their own lacked the buying power to match the department stores. But high sales volumes could be obtained by combining many spatially separate outlets in “chains” with a centralized buying and administrative authority. Current examples include Barnes & Noble, Home Depot, and Wal-Mart. One of the early chains, still with us today, was the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, founded in 1859. From an original line restricted to tea and coffee, the company expanded in the 1870s to include a general line of groceries. In 1879, F. W. Woolworth began the venture that was to make him a multimillionaire when he opened variety stores carrying articles that sold for no more than a dime. By 1900, tobacco stores and drugstores were often organized in chains, and hardware stores and restaurants soon

Began to fall under centralized managements. By 1920, grocery, drug, and variety chains were firmly established as a part of the American retail scene. A few companies then numbered their units in the thousands, but the great growth of the chains was to come in the 1920s and 1930s—along with innovations in physical layout and the aggressive selling practices that would incur the wrath of the independents.

Although e-commerce has produced a tremendous resurgence of ordering goods by mail in the United States, it is probably difficult for the modern urban resident to imagine the thrill that “ordering by mail” once gave Americans. Indeed, for many American families in the decades before World War I, the annual arrival of a catalog from Montgomery Ward or Sears, Roebuck and Company was an event awaited with great anticipation. Although Montgomery Ward started his business with the intention of selling only to Grangers, he soon included other farmers and many city dwellers among his customers. Both Montgomery Ward and Sears Roebuck experienced their great growth periods after they moved to Chicago—a vantage point from which they could sell, with optimum economies of shipping costs and time, to eager Midwestern farmers and to both coasts as well. The establishment of rural free delivery (1896) and parcel post (1913) by the U. S. Post Office were godsends to mail-order houses. Rural free delivery in particular was the product of a long campaign by farmers; the slogan was “every man’s mail to every man’s door.” By 1920, however, towns were readily accessible to farmers, who could now make their own purchases. If the mail-order houses were to remain important merchandisers, they would have to modify their selling methods.

World History

World History