Horizontal mergers, the type typical of the first phase, combine firms that produce identical or similar products. During the 1870s and 1880s, as the railroads extended the formation of a national market, many existing small firms in the consumer-goods industries experienced a phenomenal increase in the demand for their products. This was followed by an expansion of facilities to take advantage of the new opportunities. Then, in many areas, there was great excess capacity and “overproduction.” When this occurred, prices dropped below the average per-unit production costs of some firms. To protect themselves from insolvency and ultimate failure, many small manufacturers in the leather, sugar, salt, whiskey, glucose, starch, biscuit, kerosene, and rubber boot and glove industries (to name the most important) combined horizontally into larger units. They then systematized and standardized their manufacturing processes, closing the least-efficient plants and creating purchasing, marketing, finance, and accounting departments to service the units that remained. By 1893, consolidation and centralization were well under way in those consumer-goods industries that manufactured staple household items that had long been in use. Typical of the large firms created in this way were the Standard Oil Company of Ohio (after 1885, the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey), the Distillers’ and Cattle Feeders’ Trusts, the American Sugar Refining Company, and the United States Rubber Company.

Of the firms that became large during the first wave of concentration, the most spectacular was Standard Oil. From its beginnings in 1860, the petroleum-refining business had been characterized by a large number of small firms. By 1863, the industry had more than 300 firms, and although this number had declined by 1870 to perhaps 150, competition was intense, and the industry was plagued by excess capacity. “By the most conservative estimates,” write Harold Williamson and Arnold Daum, “total refining capacity during 1871-1872 of at least twelve million barrels annually was more than double refinery receipts of crude, which amounted to 5.23 million barrels in 1871 and 5.66 million barrels in 1872” (1959, 344). An industry with investment in fixed plant and equipment that can turn out twice the volume of current sales is one inevitably characterized by repeated failures (usually in the downswing of the business cycle) and highly variable profits in even the most efficient firms.

John D. Rockefeller, the man who would become the symbol of America’s rise to world industrial leadership, got his start in business at the age of 19, when he formed a

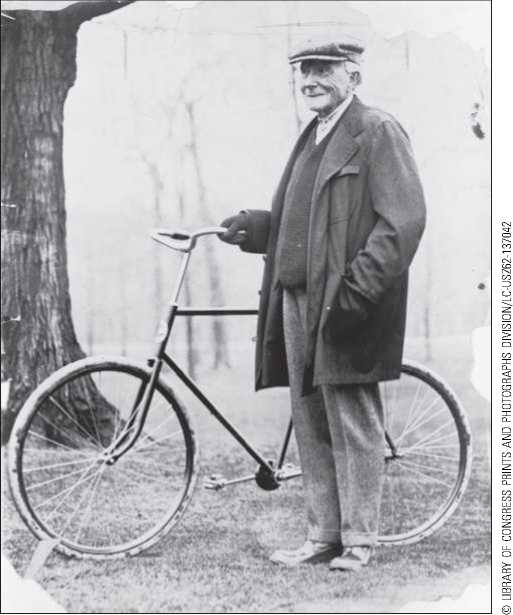

John D. Rockefeller, archetype of the nineteenth-century businessman, brought discipline and order to the unruly oil industry, parlayed a small stake into a fortune estimated at more than $1 billion (about $20 billion in today’s money), and lived in good health (giving away some of his millions) until 96 on a regimen of milk, golf, and river watching.

Partnership with Maurice B. Clark to act as commission merchants and produce shippers. Moderately wealthy even before the end of the Civil War, Rockefeller entered the oil business in 1862, forming a series of partnerships before consolidating them as the Standard Oil Company of Ohio in 1869. Rockefeller’s company was perhaps the best managed in the industry, with two large and highly efficient refineries, a barrel-making plant, and a fleet of tank cars. Standard’s holdings grew steadily during the 1870s, largely through the acquisition of refineries in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and New York, as well as in Ohio. Demanding and receiving rebates on oil shipments (and even drawbacks on the shipments of competitors), Standard Oil made considerable progress in absorbing independent refining competition. By 1878, Standard Oil either owned or leased 90 percent of the refining capacity of the country. The independents that remained were successful only if they could produce high-margin items, such as branded lubricating oils, that did not require high-volume, low-cost manufacture.

To consolidate the company’s position, a trust agreement was drawn in 1879 according to which three trustees were to manage the properties of Standard Oil of Ohio for the benefit of Standard stockholders. In 1882, the agreement was revised and amended; stockholders of 40 companies associated with Standard turned over their common stocks to nine trustees. The value of properties placed in the trust was $70 million (about $9.5 billion in today’s money using unskilled wages as the inflator), against which

700,000 trust certificates were issued.

The agreement further provided for the formation of corporations in other states sharing a similar name: Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, and of New York, and so on. After the Supreme Court of Ohio ordered the Standard Oil trust dissolved in 1892, the combination still remained effective for several years by maintaining closely interlocking directorates among the major refining companies. Threatened by further legal action, company officials changed the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey from an operating to a holding company, increasing its capitalization from $10 million to $110 million so that its securities might be exchanged for those of the subsidiaries it held. It secured all the advantages of the trust form, and, at least for a time, incurred no legal dangers. Thus, Standard Oil went from a trust to a holding company after the successful combination had long since been achieved. Rockefeller had become one of America’s most successful entrepreneurs, but also one of its most controversial. (See Economic Insight 17.2)

STANDARD OIL AND PREDATORY PRICING

John D. Rockefeller was blessed with many critics, but the most effective by far was the crusading journalist (then known as a muckraker) Ida M. Tarbell. Tarbell’s father had been a barrel maker in the early days of the oil boom, and blamed his eventual loss of employment on Standard Oil, which may well have been an inspiration for Tarbell’s writings. In any case, Tarbell wrote a series of carefully documented and highly critical articles that were published in 1904 as The History of the Standard Oil Company. The public outcry against Standard Oil ignited by this book was one of the main forces behind the Supreme Court’s decision to break up the company. Tarbell made many criticisms of Standard Oil, but one in particular has stirred considerable controversy among economists: that Standard Oil had engaged in “predatory pricing.” The claim was that Rockefeller had systematically ruined his competitors by selling kerosene at a price below the average cost of production until his competitors were driven into bankruptcy. Rockefeller then bought them for a song, and made back everything he had lost by raising the price of kerosene to a higher level than would have been possible if he still faced competition. Many economists, however, have been skeptical. For one thing, the process seems to waste profits. Why not offer to buy the competitor at a price that includes part of the increased profits possible from monopoly? That way, prices could be increased to monopoly levels without going through a period of losses. John McGee (1958) made this point in a classic article that reexamined the testimony presented at the 1911 trial of Standard Oil. McGee concluded that there was little evidence that Rockefeller

Had engaged in predatory pricing. Still the claim that Standard Oil or other firms have at times engaged in predatory pricing continues to attract media attention. Later R. Mark Isaac and Vernon L. Smith (1985) used laboratory experiments to test the viability of predatory pricing. They concluded that predatory pricing was unlikely, at least in the experimental formats they explored.

World History

World History