The third major category of Cold War stories was epic renderings of history and fantasy: stories depicting the past or future in real or imagined worlds told on an immense canvas, frequently with a strong dose of morality and self-righteousness. At the outset of the conflict, such epics helped to sustain wartime cohesion and cement loyalties and identities. As the Cold War progressed, history and fantasy allowed vicarious participation in events and mobilized people behind their leaders’ projects through grand narratives of good versus evil and tales of national destiny. In time, as the conflict weighed heavily on its participants, both history and fantasy also provided a language for dissent.

In American television, literature, and film, the Cold War underpinned the production of science fantasy and historically inspired fiction. Biblical/classical epics, war, and western genres all carried obvious ideological freight. The epic had its roots in nineteenth-century pageants and a distinguished career in the silent era, but the Cold War cinema took it to new heights as it became a stage on which the cultural power of America could be displayed. The government did not need to ask Hollywood to do this, but the spirit of national certainty and righteousness which animated Washington was just as much a part of Hollywood life. Major directors, producers, and executives, including Cecil B. DeMille, Daryl F. Zanuck, and the president of the Motion Picture Association of America, Eric Johnston, were true believers in the need for movies to play a role in rallying the nation and disseminating American values around the world.

Cold War Hollywood produced a new generation of biblical and classically themed films. While the stories suggested an American ambivalence toward empire, the films themselves were part of an imperial system displaying the cultural power of the society capable of mounting such a spectacle and showcasing America’s religiosity in contrast to Soviet hostility to faith. Cecil B. DeMille presented his remake of The Ten Commandments in 1956 as an attempt to assert the common tradition of Christians, Muslims, and Jews in the face of God-less Communism. More than this, American diplomats encouraged the making of biblical epics because the necessary locations happened to be in places where US investment could make a real political difference, most especially in Italy, the one European country where the Communists had a chance to come to power constitutionally. Use of the classical genre to challenge the Cold War status quo was rare, though Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960) was open to radical interpretations and suffered during the production process as a result.677

The epic war film allowed Hollywood to stage stories of glory on a grand scale and to inject contemporary comment, too. Films of the late 1940s and early 1950s typically included a recruiting scene in which an authority figure spoke of the necessity for each generation to defend democracy, and directors enjoyed the help of the Pentagon to stage mass battle scenes. War films raised some diplomatic difficulties, especially as the villains - Germany and Japan - were now Cold War allies. Hollywood provided a succession of "good Germans" and films like The Enemy Below (Dick Powell, dir., 1957) ended with hope for future friendship. Noble Japanese appeared somewhat later. But the American war film was transformed by the Vietnam War. As audiences stayed away from flag-waving pictures like John Wayne’s The Green Berets in 1968, Hollywood injected counter-cultural satire into its war movies or told stories that could be read as either indictments or celebrations of militarism, the best example being Patton (Franklin J. Schaffner, dir., 1970).

The genre ofwestern movies followed much the same trajectory as the war story with films in the immediate postwar period highlighting the "need" for military preparedness. The western that had previously dwelt on the heroic individual now celebrated team work and romanticized army life in a succession of cavalry westerns. As the Cold War shifted to the Third World in the late 1950s, so westerns depicted American heroes saving Mexican farmers from bandits who appeared as thinly disguised Communists. The special status of the western within the American imagination meant that it provided an ideal space to explore responses to the experience of American power, and hence the western was transformed by the US experience in Vietnam into a major site for the reexamination of the sins of America’s past and present. Hollywood restaged My Lai by proxy in the West in films like Soldier Blue (Ralph Nelson, dir., 1970) in which the 7th Cavalry was seen massacring Native American women and children, long before it tackled such issues head-on in an explicit representation of Vietnam.

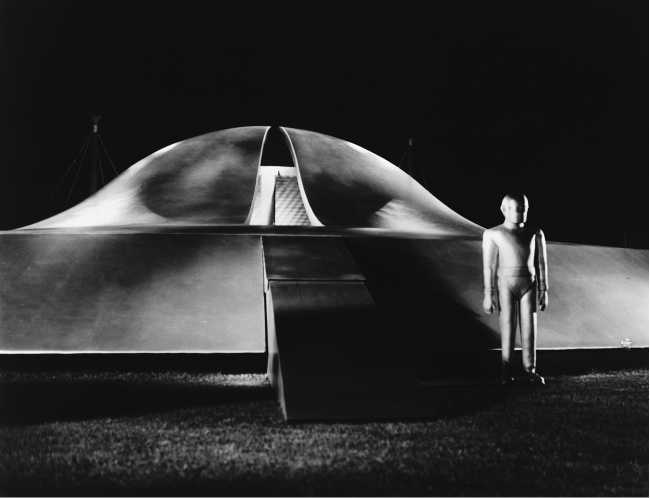

33. Science fiction provided a fertile medium in which to discuss the fears raised by the Cold War, as with Robert Wise's 1951 film, The Day the Earth Stood Still, in which aliens help to prevent a nuclear war.

American science fiction also displayed both patriotism and dissent. The epic fantasy films of the 1950s like This Island Earth (Joseph M. Newman, dir., 1955) openly displayed the familiar Cold War themes. The world is pulled from the brink of a nuclear war by an alien in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951). American television in the 1960s provided Star Trek (1966-69), which mixed both the imperial spirit to “boldly go where no man has gone before" and a pseudo-Soviet enemy in the Klingons, with challenges to Cold War thinking as a Russian crew member and episodes which critiqued the arms race and the balance of terror.678 When, in the 1970s, Hollywood could no longer display the religiosity of the epic, the patriotic certainty of the war film and the grand narrative of the western, these genres reappeared in hybrid science fiction form utterly extracted from any political context. The best example of this was Star Wars (George Lucas, dir., 1977).

Western Europe also produced Cold War epic histories and fantasies rallying the population for confrontation with the Soviet Union. Innumerable war stories sustained an anti-totalitarian ideology. British science fiction was populated by invading totalitarian races from the Treens of The Eagle’s Dan Dare comic strip (1957-69) to the Daleks of BBC TV’s Doctor Who (1963-89, 2005- ). As World War II receded and the Cold War came into question, such stories were increasingly told with a knowing irony that sometimes bordered on camp. The most expansive epic of the period was J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. While Tolkien resisted all attempts to impose allegory on his work and denied that his "Ring of Power" was a cipher for the atomic bomb, his story of virtuous individuals struggling against powers of darkness played into the Cold War self-consciousness of Europeans and Americans. Much of the plot concerned forging and maintaining alliances in ways that would have been instantly recognizable to the politicians of the era.

The Soviet bloc’s own epic storytelling trod surprisingly similar terrain to Western culture. Science fiction played a prominent role and innumerable epic dramas recalled the glories of the past. In Brezhnev’s Russia, the cult of the "Great Patriotic War" reached unprecedented heights - quite literally - with the erection of vast war memorials and the creation of movies to match. The war continued to be offered to the people as the source of certainty and unity well into the 1970s. It was much the same story in East German film and television with numerous tales of heroic German Communist resistance to Nazi tyranny. The state control of the media in the East meant that any criticism had to be far more veiled than in the West, but nonetheless, some filmmakers used historical stories to air dissent. In Poland, myths of the war (and the ideological foundations of that state) were laid bare in films like Popiol i diament [Ashes and Diamonds] (Andrzej Wajda, dir., 1958) and the bleak POW segment of Eroica (Andrzej Munk, dir., 1957). In Hungary, director Miklos Jancso’s chose stories that on the surface explored the revolutionary past but underneath allowed Austrian or White Russian villains to stand in for the USSR of 1956. Such films questioned the certainties of the revolution, the Communist state, and the Cold War division ofthe world, but they were but a shadow of the dissent that would erupt in the later 1970s.679

The years of detente saw a strange phenomenon in Cold War filmmaking - the East-West co-production. Some of the movies created in this way self-consciously tackled themes of interdependence. In the Italian-Soviet co-production The Red Tent (Mikhail Kalatozov, dir., 1969), a Soviet icebreaker strives to rescue the survivors of the Italia airship expedition to the North Pole.680 Waterloo (Sergei Bondarchuk, dir., 1970), also a Soviet-Italian co-production, recalled the international coalition against Napoleon. The only big US-Soviet co-production was Twentieth Century Fox's remake of The Blue Bird (George Cukor, dir., 1976), made in the USSR and starring Elizabeth Taylor, character actors from both sides of the Iron Curtain, and a line up of Soviet ballet talent. It took millions to make and flopped miserably.

World History

World History