Many historical surveys of the domestic Cold War begin with the dramatic story of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s rise to power. In some ways, this is appropriate, for it forces us to acknowledge up front just how potent and destructive - even if not complete - the Cold War’s national security mentality could be. "McCarthyism" is the term generally used to describe those early years of the domestic Cold War but, as historians have documented, its reach went well beyond the man himself. McCarthyism drew heavily on the dualistic language (good and evil) and binary frameworks (aligned and

Non-aligned) deployed by foreign policymakers, but the synergy between McCarthyism and the Cold War did not mean they were one and the same. In fact, red scares marked earlier historical periods, as was the case after World War I and during the heated battles over the New Deal. Furthermore, although the Cold War certainly gave McCarthy his vigor and stature, that same Cold War nudged him out ofmainstream politics. Thus, the relationship between McCarthyism and the Cold War is complex, with each giving the other some vigor and credibility, but also some ideological instability.

Scholars have long debated McCarthyism’s emergence, its reconfiguration of postwar politics, and its eventual ebb. Early observers first suggested that McCarthy was the product of a kind of homegrown conservative populism, whose followers harbored class resentments and were particularly susceptible to the remonstrations of irrational fanatics. A new generation of scholars emerged in the 1970s, rejecting the psychological inflections of this earlier work, revealing that McCarthy himself was not the story. As Robert Griffith and Athan Theoharis then claimed, McCarthy "was the product of America’s cold-war politics, not its progenitor," and his followers could not be cast as premodern malcontents.669

Most historians now agree that McCarthyism "was primarily a top-down phenomenon," not a grassroots social movement. Its more elite progenitors came from the political mainstream, from both parties, from various branches of government and law enforcement, and from corporations and civic arenas. As Ellen Schrecker has shown, "there was not one, but many McCarthyisms, each with its own agenda and modus operandi. " Its diverse sources did not prevent coordination and coherence, however. As Schrecker reveals, the campaign against Communism "was, above all, a collaborative project." Still, initially, it was the power of a smaller group, McCarthy among them, but J. Edgar Hoover in particular, who managed to convince a larger group of political elites that outing and then ousting Communists should be the state’s full-time pursuit. They did so by borrowing heavily from diplomatic discourses that exaggerated dangers and simplified complexities, and then by showing how such a politics of fear could reap myriad tangible gains in political, economic, and cultural arenas. Once the logic and rhetorical frameworks of Cold War anti-Communism were in place, political leaders (the sitting and the aspiring) had a readymade set of speeches and shaming rituals

At their disposal, and corporate and civic elites could borrow heavily from these scripts to conduct their own crusades.670

A few examples of McCarthyism in action in different settings can illustrate its diverse applications, its destructive power, and its limitations. The massive strike wave after World War II has been well documented by historians as part of a larger story of American workers seeking their share of capitalist abundance - the peace dividend, in effect, promised to them during the war. Labor remained an important constituency in the eyes of American foreign-policy leaders; its productive muscle and political power would be crucial for a smooth reconversion and for future economic security. The postwar strike waves, however, hinted that restive workers might have their own blueprint for the postwar world, one that prioritized domestic prosperity above national security - although the two were not mutually exclusive, as Cold Warriors liked to point out. To gain labor’s firm backing, Secretary of State George Marshall warned the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1947 that it had a special obligation to oppose "enemies of democracy" who might attempt to erode workers’ faith in internationalist plans, such as his own.671

The political background noise for Marshall’s speech was the brewing Cold War, as President Harry S. Truman’s loyalty program and his landmark Truman Doctrine were pushed forward that same year. These larger policies touched labor directly through the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, a piece of legislation that attacked labor’s actual and potential power - which seemed even more formidable after the strike waves. A clause contained in Taft-Hartley required union leaders to sign an affidavit avowing they were not Communists and, although this was but a small part of the Taft-Hartley legislation, it nevertheless signaled an anti-Communist offensive against the labor movement’s most visionary and progressive wing. Corporations could now use the loyalty pledge to pursue longstanding anti-union agendas; buttressed by patriotic bluster and national security justifications, management could refuse to negotiate with unions whose leaders had not signed.

Taft-Hartley also emboldened anti-Communists within the CIO, who saw an opportunity to weaken their own left flank. Indeed, the loyalty pledge resurrected bitter internecine conflicts within the movement about the role of Communists in progressive causes. After the war, labor’s moderates were hoping for a new power-sharing arrangement with government and business,

And they could ill afford the taint of radicalism. The CIO's top leadership thus played the loyalty game, sacrificing some of its own progressive membership to broker a closer relationship with President Truman, whose veto of Taft-Hartley persuaded them that the White House was the best guarantor of labor's interests.672 In the end, this whole episode of domestic anti-Communism “wiped out an entire generation of activists," argues Schrecker. Rather than pushing new initiatives forward or moving outward into new industries, “the labor movement turned inward and raided its own left wing." More than that, the Taft-Hartley fight diminished the power of ordinary workers; it diverted attention and resources from fighting for the bread-and-butter issues that mattered most to those who punched the clock and signed a union card, but who might not have otherwise thought of themselves as particularly political.673

Taft-Hartley's passage in Congress - over Truman's veto - suggests that anti-Communism had gained currency among elected officials who saw no political risk to themselves or their party for supporting it. As a piece of legislation, Taft-Hartley represents a moment in the domestic Cold War when politicians began to codify the ideology of anti-Communism into state policy. Its non-Communist affidavit was part of a larger phenomenon in which federal, state, and municipal governments began to use their regulatory and enforcement powers to screen, investigate, and remove, if necessary, alleged subversives. The use and abuse of this power illustrate how McCarthyism increasingly intersected with the formation of the evolving national security state.

This new Cold War security state was a massive bureaucracy or, as Daniel Yergin has put it, “a state within a state." It encompassed the federal government's powers of surveillance, investigation, lawmaking, and enforcement. Emerging in the late 1940s, it grew to include a wide swath of elected leaders, appointed officials, affiliated intellectuals, think tanks, law-enforcement officials and courts, and their cultural brokers - nongovernmental organizations such as the American Legion and the Boy Scouts, and parts of the national media, who put the security threats into terms everyone could understand. The term “national security" itself was common parlance in the Cold War, and its potency was its elasticity and ambiguity. It was a cluster of ideas about

Foreign and domestic affairs that framed all global developments as potential threats to US interests. "National security" was used widely, many would say recklessly, to understand a whole range of issues, seemingly disconnected from US diplomacy. The energy and resources devoted to the creation of this state set a new cultural tone - a kind of ambient militarism in which military priorities and mindsets came to dominate popular discourse.674

The new national security state was what Gary Gerstle has called a "disciplinary state," a government with formidable powers to spy, prosecute, and purge.675 Nowhere was McCarthyism’s state power more clear than in the actions of J. Edgar Hoover and his Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), whose maneuvers were more covert but just as harmful as Congress’s show trials. In fact, Schrecker argues that McCarthyism’s "bureaucratic heart" was in the FBI, and that McCarthyism might more accurately be called "Hooverism." Her research shows that it was Hoover’s FBI that "designed and ran much of the machinery" of the government’s pursuit of Communists. From 1946 to 1952, the Bureau added close to 3,500 staff to investigate some 2 million federal employees. Truman’s loyalty program had Hoover’s imprint, with its capricious standards for what constituted credible evidence, and its refusal to allow the accused to know or confront their accusers. 676 Truman himself was a liberal anti-Communist who was more than uneasy about the Bureau’s overreach. He especially disliked Hoover’s tactics. As Congress continued to pass legislation that further narrowed the range of acceptable speech, such as the 1950 McCarran Act, Truman cautioned against excesses. He warned it was "entirely contrary to our principles" to ban the Communist Party, and that the FBI was bordering on Gestapo-like tactics in its approach. 677

But as was the case for perhaps all elected officials in this first blush of the Cold War, Truman’s political calculations circumscribed his own speech and actions. Even as he tried genuinely to curb anti-Communist hysteria, he wanted to protect his own diplomatic and domestic agendas and to insulate his party from red-baiting. Thus, he made concessions, such as the federal loyalty program, that gave momentum to the very political forces he hoped to restrain. The same was true for Dwight Eisenhower, a more moderate

Republican, less indulgent of his fellow conservatives’ red panics, but more worried about how an outright confrontation with McCarthy and the myriad anti-Communist factions in and around Congress might fracture his own party. Both presidents, then, had principled objections, but both backed away from taking strong and sustained public stands against either McCarthy’s or Hoover’s abuses of power. As some have argued, McCarthyism had legs because of both the "actions and inactions" of elected officials in the White House and Congress.678

McCarthyism’s political clout went well beyond party politics and the formal powers of the national security state. As an elite-inspired phenomenon, it trickled down into state and local bureaucracies, private corporations, and civic groups. The familiarity of McCarthyite rhetorical frameworks, the "one size fits all" approach to identifying Communists, and the showy shaming rituals allowed even amateurs to play the game. Many citizens participated in a kind of grassroots anti-Communism, taking their cues from those higher up and fashioning a generic national anti-Communism into a style that fit their local situations. Much has been written about Cold War culture - the films, television shows, comic books, and advertising that reflected and projected Americans’ fears of Communism. Though fascinating, these are limited indices of how citizens responded to and participated in the red scare. How did people actually "do McCarthyism," so to speak? Or as Richard Fried asks: "How did anti-Communism settle into people’s lives at times HUAC [House Un-American Activities Committee] or McCarthy _ were not in the news?"679

Studies ofCold War parades and public commemorations suggest that antiCommunists’ efforts to reach the grassroots yielded mixed results. In 1948, New York City’s Veterans of Foreign Wars organized locally what later became a national Loyalty Day whose purpose was "to show before the world that Americans rejected communism," as Fried puts it. Hundreds of thousands of regular citizens across the nation marched from the late 1940s into the mid-1950s, mainly tugged by their unions, schools, churches, or ethnic

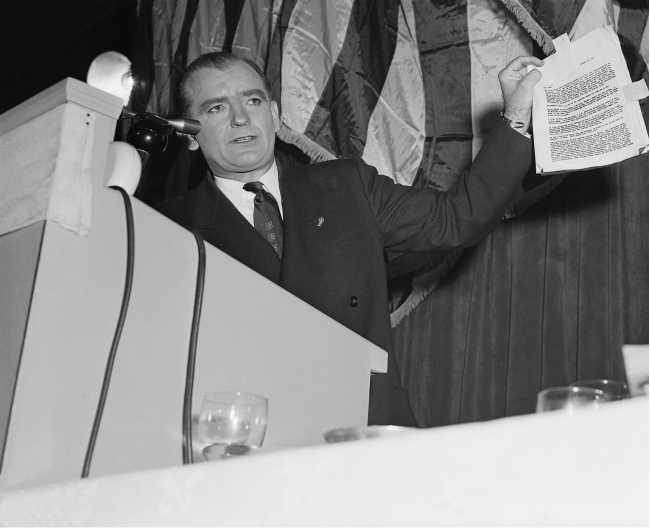

34. Senator Joseph R. McCarthy waves a document while delivering a "report” on Democratic presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson, 1952. His anti-Communist attacks helped shape American political culture during the early Cold War.

Associations. But this patriotic pageantry did not capture the nation; presidents paid homage but did not attend, and citizens’ interest ran hot and cold.680

Even something like the Freedom Train, a traveling exhibition of the United States’ most sacred documents, demanding no participation - just genuflection - could not compel citizens to practice Cold War anti-Communism in the way sponsors intended. Traveling to hundreds of cities, loaded with documents already sanitized by organizers to remove any hint of conflict over race or New Deal class struggles, the Freedom Train attracted massive crowds but also pointed criticism. Poet Langston Hughes and actor Paul Robeson raised the painfully obvious contradictions of taking a Freedom Train to the Jim Crow South. Often, the Train’s visit to a city or town motivated locals to organize a Rededication Week, where they would pledge to practice anew what the Freedom Train preached. But here, too, people drew different lessons and

Interpreted the nation’s documents in ways that departed from the Train’s antiCommunist origins. Rededication Week in Iowa City, for instance, urged racial tolerance and celebrated women’s rights, and in Cincinnati one club used the week to organize a "Stop the Bigot" rally.681

Such fickle applications of Cold War dogma have made it difficult for scholars to quantify McCarthyism’s impact. Schrecker offers some numbers: two deaths - Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, several hundred imprisoned, and some ten thousand to twelve thousand dismissed from their jobs. Griffith has tallied 135 congressional investigations, led mainly by the House Un-American Activities Committee, from 1945 to 1955. His analysis of public opinion polls reveals both support for and sentiment against McCarthy himself but a persistent intolerance for Communism, in general. Polling data also show, however, that anti-Communism did not always trump other concerns. In partisan politics, for example, Richard Fried catalogs the national and state elections in which red-baiting increasingly permeated election rhetoric. He detects a "full-blown electoral McCarthyism" by 1950, when establishing one’s anti-Communist credentials became a central motif in victorious Senate, House, and gubernatorial campaigns. And yet, he argues, McCarthyism’s electoral impact was never as great as politicians and the press believed at the time. Polls from the early 1950s show that voters’ motivations for casting a ballot did not turn on the issue of Communism; their concerns were more immediate, such as the high cost of living and taxes. Certainly, candidates could handily transform these issues into anti-Soviet screeds, but politicians’ rhetoric has never been a reliable index of voter rationale and intent. Thus, "while the specter of communism has haunted US politics since 1917," Fried concludes, "it never prowled full-time."682

World History

World History