Although Germany lost World War I and suffered severe economic and political problems as a result, it emerged from the war with a strong film industry. From 1918 to the Nazi rise to power in 1933, the German film industry ranked second only to Hollywood in technical sophistication and world influence. Within a few years of the armistice, German films were seen widely abroad, and a major stylistic movement, Expressionism, arose in 1920 and continued until 1926. The victorious France could not rejuvenate its film industry, so how did Germany’s become so powerful?

The German industry’s expansion during World War I was due largely to the isolation created by the government’s 1916 ban on most foreign films. The demand by German theaters led the number of producing companies to rise from 25 (1914) to 130 (1918). By the end of the war, however, the formation of the Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft (Ufa) started a trend toward mergers and larger companies.

Even with this growth, if the government had lifted the 1916 import ban at the end of the war, foreign films might have poured in again— chiefly from the United States. Unlike the situation in France, however, the German government supported filmmaking throughout this period. The ban on imports continued until December 31, 1920, giving producers nearly five years of minimal competition in their domestic market. The expansion of the war years continued, with about 300 film production companies forming by 1921. Moreover, by 1922, most anti-German sentiment in enemy countries had been broken down, and German cinema became famous internationally.

Ironically, much of the film industry’s success came while the nation underwent enormous difficulties stemming from the war. By late 1918, the war had pushed the country deep into debt, and there was widespread

Hardship. During the last month of the war, open revolt broke out, demanding the end of the monarchy and the war. On November 9, just two days before the armistice, the German Republic was declared, abolishing the monarchy. For a few months, radical and liberal parties struggled for control, and it seemed as if a revolution similar to the one in Russia would occur. By mid-January 1919, however, the extreme left wing was defeated, and an election led to a coalition government of more moderate liberal parties. In general, the German political climate drifted gradually toward the right during the 1920s, culminating in the ascension of the Nazi party in 1933.

Internal strife was intensified by the harsh measures the Allies took in their treatment of Germany. The war officially ended with the signing of the infamous Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919. Rather than attempting to heal the rift with Germany, Great Britain and France insisted on punishing their enemy. A “war guilt” clause in the treaty blamed Germany as the sole instigator of the conflict. Various territories were ceded to Poland and France (with Germany losing 13 percent of its prewar land). Germany was forbidden to have more than

100,000 soldiers in its army, and they were not to carry weapons. Most crucially, the Allies expected Germany to pay for all wartime damage to civilian property, in the form of money and goods. (Only the United States demurred, signing its own peace treaty with Germany in 1921.) Resentment over these measures eventually helped right-wing parties come to power.

In the short run, these reparations gradually pushed the German financial system into chaos. The reparations arrangement required that Germany regularly send high payments in gold and ship coal, steel, heavy equipment, food, and other basic goods to the Allies. Although Germany was never able to fulfill the amounts demanded, domestic shortages soon developed and prices rose. The result was inflation, beginning at the war’s end and becoming hyperinflation by 1923. Food and consumer goods became scarce and outrageously costly. In early 1923, the mark, which had been worth approximately 4 to the dollar before the war, sank to about 50,000 to the dollar. By the end of 1923, the mark had fallen to around 6 billion to the dollar. People carried baskets of paper money simply to purchase a loaf of bread.

It might seem at first glance that such severe economic problems could not benefit anyone. Many people suffered: retirees on pensions, investors with money in fixed-rate accounts, workers whose earnings lost value by the day, renters who saw housing costs spiral upward. Big industry, however, benefited from high inflation. For one thing, people had little reason to save, since money lost its value sitting in a bank or under a mattress. Wage earners tended to spend their money while it was still worth something, and movies, unlike food or clothing, were readily available. Film attendance was high during the inflationary period, and many new theaters were built.

Moreover, inflation encouraged export and discouraged import, giving German companies an international advantage. As the exchange rate of the mark fell, consumers were less likely to purchase foreign goods. Conversely, exporters could sell goods cheaply abroad, compared with manufacturers in other countries. Film producers benefited from this competitive boost. Importers could bring in relatively few foreign films, while countries in South America and eastern Europe could buy German films more cheaply than they could the Hollywood product. Thus, for about two years after the war, the German import ban protected the film market from competition, and even after imports were permitted in 1921, unfavorable exchange rates boosted the domestic cinema.

The favorable export situation fostered by high inflation fit in with the film industry’s plans. Even during the war, the growth of the industry led to hopes for export. But what sorts of films would succeed abroad? More than any other country in postwar Europe, Germany found answers to that question.

GENRES AND STYLES OF GERMAN POSTWAR CINEMA

Partly because the German film industry operated in near isolation between 1916 and 1921, there were few radical changes in the types of films being made. The fantasy genre continued to be prominent, typified by films starring Paul Wegener, like The Golem (1920, Wegener and Henrik Galeen) and Der verlorene Schatten (“The Lost Shadow,” 1921, Rochus Gliese). Directly after the war, the leftist political climate led to a brief abolition of censorship, and that in turn fostered a vogue for films on prostitution, venereal disease, drugs, and other social problems. The widespread belief that such films were pornographic led to the reinstitution of censorship. The same sorts of comedies and dramas that had dominated production in Germany and most other countries during the mid-teens continued to be made. We can, however, single out a few major trends of genre and style that gained prominence in the postwar era: the spectacle genre, the German Expressionist movement, and the Kammerspiel film.

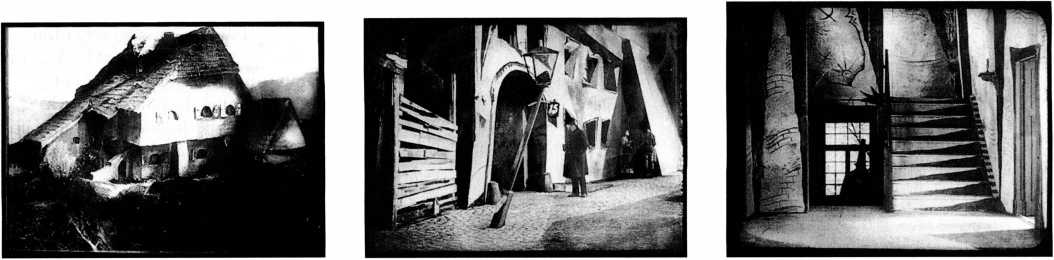

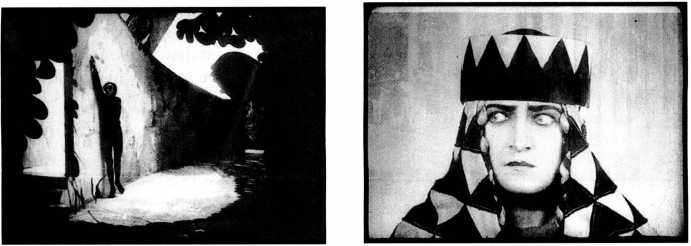

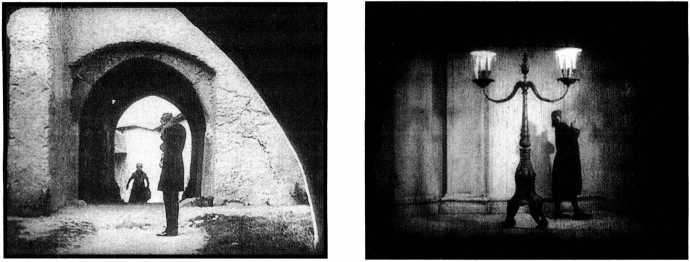

5.2 The heroine of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari wanders through the Expressionist carnival set. It almost seems that she is made of the same material as the fairground setting.

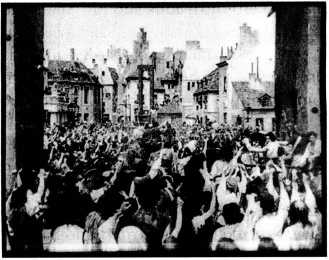

5.1 In Madame Dubarry, large sets and hundreds of extras re-create revolutionary Paris.

Before the war, the Italians had gained worldwide success with historical epics such as Quo Vadis? and Cabiria. After the war, the Germans tried a similar tactic, emphasizing historical spectacles. Some of these films attained a success similar to that of the Italian epics and, incidentally, revealed the first major German director of the postwar era, Ernst Lubitsch.

Spectacular costume films appeared in a number of countries, but only companies able to afford large budgets could use them to compete internationally. Hollywood, with its high budgets and skilled art directors, could make Intolerance or The Last of the Mohicans, but productions on this scale were rare in Great Britain and France. During the inflationary period, however, the larger German companies found it relatively easy to finance historical epics. Some firms could afford extensive backlots, and they expanded studio facilities. The costs of labor to construct sets and costumes were reasonable, and crowds of extras could be hired at low wages. The resulting films were impressive enough to compete abroad and could earn stable foreign currency. When Ernst Lubitsch made Madame Dubarry in 1919, for example, the film reportedly cost the equivalent of about $40,000. Yet when it was released in the United States in 1921, experts there estimated that such a film would cost perhaps $500,000 to make in Hollywood— at that time, a high price tag for a feature film.

Lubitsch, who became the most prominent director of German historical epics, had begun his film career in the early 1910s as a comedian and director. His first big hit came in 1916 with Schuhpalast Pinkas (“Shoe-Palace Pinkas”), in which he played a brash young Jewish entrepreneur. It was his second film for the Union company, one of the smaller firms that merged to form Ufa, where he directed a series of more prestigious projects. Ossi Oswalda, an accomplished comedienne, starred in several comedies directed by Lubitsch in the late teens, including Die Austernprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” 1919) and Die Puppe (“The Doll,” 1919). But it was with Polish star Pola Negri that Lubitsch achieved international recognition.

Negri and Lubitsch first worked together in 1918 on Die Augen der Mumie Ma (“The Eyes ofthe Mummy Ma”). This melodramatic fantasy took place in an exotic Egyptian locale and was typical of German productions of the late 1910s. Negri’s costar was the rising German actor Emil Jannings, and with these two Lubitsch made Madame Dubarry (1919), based loosely on the career of Louis XV’s mistress (5.1). It was enormously successful, both in Germany and abroad. Lubitsch went on to make similar films, most notably Anna Boleyn (1920). In 1923, he became the first major German director hired to work in Hollywood. (Negri had preceded him under a long-term contract with Paramount.) Lubitsch quickly became one of the most skillful practitioners of the classical Hollywood style of the 1920s.

Historical spectacles remained in vogue as long as severe inflation enabled the Germans to sell them abroad at prices that no other country’s film industry could match. But in the mid-1920s, the end of inflation dictated more modest budgets, and the spectacle genre became considerably less important.

The German Expressionist Movement

In late February 1920, a film premiered in Berlin that was instantly recognized as something new in cinema: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Its novelty captured the public imagination, and it was a considerable success. The film used stylized sets, with strange, distorted buildings painted on canvas backdrops and flats in a theatrical manner (5.2). The actors made no attempt at realistic performance; instead, they exhibited jerky or dancelike movements. Critics announced that the Expressionist style, by then well established in most other arts, had made its way into the cinema, and they debated the benefits of this new development for film art.

A Chronology of German Expressionist Cinema

February: Decla company releases Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet ofDr. Caligari), directed by Robert Wiene; it starts the Expressionist movement.

Spring: Decla and Deutsche Bioscop merge to form Decla-Bioscop; under Erich Pommer's supervision, Decla-Bioscop produced many of the major Expressionist films.

Algol, Hans Werckmeister

Der Golem (The Golem), Paul Wegener and Carl Boese Genuine, Robert Wiene

Von Morgens bis Mitternacht (From Morn to Midnight), Karl Heinz Martin Torgus, Hans Kobe

November: Ufa absorbs Decla-Bioscop, which remains a separate production unit under Pommer's supervision.

Der mude Tod ("The Weary Death," aka Destiny), Fritz Lang Das Haus zum Mond ("The House on the Moon"), Karl Heinz Martin

Dr Mabuse, der Spieler (Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler), Fritz Lang Nosferatu, F. W. Murnau

Schatten (Warning Shadows), Artur Robison

Der Schatz ("The Treasure"), G. W. Pabst

Raskolnikow, Robert Wiene

Erdgeist ("Earth Spirit"), Leopold Jessner

Der steinere Reiter ("The Stone Rider"), Fritz Wendhausen

Autumn: Hyperinflation ends.

Wachsfigurenkabinett (Waxworks), Paul Leni

Die Nibelungen, in two parts: Siegfried and Kriemhilds Rache ("Kriemhild's Revenge"), Fritz Lang Orlacs Hande (The Hands of Orlac), Robert Wiene

December: Ufa is rescued from bankruptcy by loans from Paramount and MGM.

Tartijff (Tartuffe), F. W. Murnau

Die Chronik von Grieshuus (The Chronicle of the Grey House), Arthur von Gerlach

February: Erich Pommer is forced to resign as head of Ufa.

September: Faust, F. W. Murnau

January: Metropolis, Fritz Lang

Expressionism had begun around 1908 as a style in painting and the theater—appearing in other European countries but finding its most intense manifestations in Germany. Like other modernist movements, German Expressionism was one of several trends around the turn of the century that reacted against realism. Its practitioners favored extreme distortion to express an inner emotional reality rather than surface appearances.

In painting, Expressionism was fostered primarily by two groups. Die Brucke (“The Bridge”) was formed in 1906; its members included Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel. Later, in 1911, Der Blaue Reiter (“The Blue Rider”), was founded; among its supporters were Franz Marc and Wassili Kandinsky. Although these and other Expressionist artists like Oskar Kokoschka and Lyonel Feininger had distinctive individual styles,

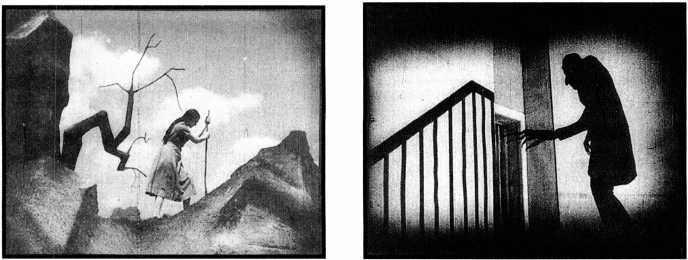

5.3 A dark shape indicates a hill, and actors stare wide-eyed or assume grotesque postures in Fritz von Unruh’s play Ein Geschlecht (1918).

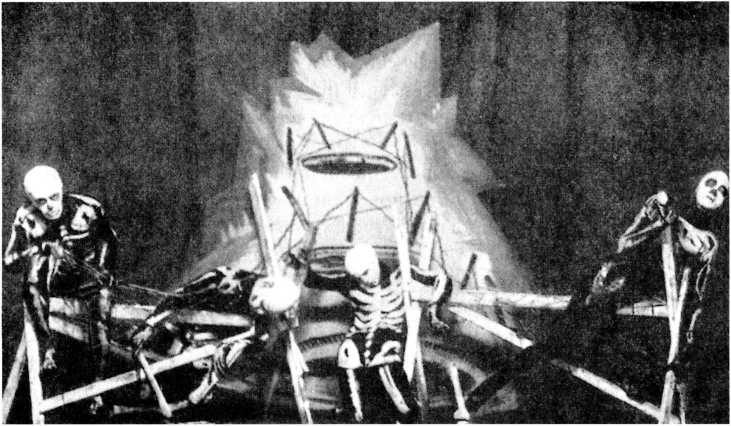

5.4 Actors costumed as skeletons writhe within an abstract landscape of barbed wire in Ernst Toller’s Die Wandlung (1919).

They shared some traits. Expressionist painting avoided the subtle shadings and colors that gave realistic paintings their sense of volume and depth. Instead, the Expressionists often used large shapes of bright, unrealistic colors with dark, cartoonlike outlines (Color Plate 5.1). Figures might be elongated; faces wore grotesque, anguished expressions and might be livid green. Buildings might sag or lean, with the ground tilted up steeply in defiance of traditional perspective (Color Plate 5.2). Such distortions were difficult for films shot on l ocation, but Caligari showed how studio-built sets could approximate the stylization of Expressionist painting.

A more direct model for stylization in setting and acting was the Expressionist theater. As early as 1908, Oskar Kokoschka’s play Murderer, Hope ofWomen was staged in an Expressionist manner. The style caught on during the teens, sometimes as a means of staging leftist plays protesting the war or capitalist exploitation. Sets often resembled Expressionist paintings, with large shapes of unshaded color in the backdrops (5.3). The performances were comparably distorted. Actors shouted, screamed, gestured broadly, and moved in choreographed patterns through the stylized sets (5.4). The goal was to express feelings in the most direct and extreme

5.5 In the Burgundian court in Siegfried, ranks of soldiers and decor alike form geometric shapes that combine into an overall composition.

5.6 In The Golem, an animated clay statue emerges onto a rooftop, looking as if he is made of the same material as his surroundings.

5.7 A symmetrical shot in Algol shows a corridor made up of repeated abstract black and white shapes and

Fashion possible. Similar goals led to extreme stylization in literature, and narrative techniques such as frame stories and open endings were adopted by scriptwriters for Expressionist films.

By the end of the 1910s, Expressionism had gone from being a radical experiment to being a widely accepted, even fashionable, style. Thus when The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari premiered, it hardly came as a shock to critics and audiences. Other Expressionist films quickly followed. The resulting stylistic trend lasted until the beginning of 1927.

What traits characterize Expressionism in the cinema? Historians have defined this movement in widely differing ways. Some claim that the true Expressionist films resemble The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in using a distorted, graphic style of mise-en-scene derived from theatrical Expressionism. Of such films only perhaps half a dozen were made. Other historians classify a larger number of films as Expressionist because the films all contain some types of stylistic distortion that function in the same ways that the graphic stylization in Caligari does. By this broader definition (which we use here), there are close to two dozen Expressionist films, released between 1920 and 1927. Like French Impressionism, German Expressionism uses the various techniques of the medium—mise-en-scene, editing, and camerawork—in distinctive ways. We shall look first at these techniques, then go on to examine the narrative patterns that typically helped motivate the extreme stylization of Expressionism.

While the main defining traits of French Impressionism lay in the area of camerawork, German Expressionism is distinctive primarily for its use of mise-en-scene. In 1926, set designer Hermann Warm (who worked on Caligari and other Expressionist films) was quoted as believing that “the film image must become graphic art.”l Indeed, German Expressionist films emphasize the composition of individual shots to an exceptional degree. Any shot in a film creates a visual composition, of course, but most films draw our attention to specific elements rather than to the overall design of the shot. In classical films, the human figure is the most expressive element, and the sets, costume, and lighting are usually secondary to the actors. The threedimensional space in which the action occurs is more important than are the two-dimensional graphic qualities on the screen.

In Expressionist films, however, the expressivity associated with the human figure extends into every aspect of the mise-en-scene. During the 1920s, descriptions of Expressionist films often referred to the sets as “acting” or as blending in with the actors’ movements. In 1924, Conrad Veidt, who played Cesare in Caligari and acted in several other Expressionist films, explained, “If the decor has been conceived as having the same spiritual state as that which governs the character’s mentality, the actor will find in that decor a valuable aid in composing and living his part. He will blend himself into the represented milieu, and both of them will move in the same rhythm.”2 Thus, not only did the setting function as almost a living component of the action, but the actor’s body became a visual element.

In practice, this blend of set, figure behavior, costumes, and lighting fuses into a perfect composition only at intervals. A narrative film is not like the traditional graphic arts of painting or engraving. The plot must advance, and the composition breaks up as the actors move. In Expressionist films the action often proceeds in fits and starts, and the narrative pauses or slows

5.8 The old, sagging house in G. W. Pabst’s Der Schatz.

5.10 A stairway in Torgus seems to lean dizzily, with a slender black triangle painted on each tread.

5.9 The leaning buildings and lamppost in Wiene’s Raskolnikow, an adaptation of Crime and Punishment.

5.11, left In this famous shot from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the diagonal composition of the wall dictates the movement of the actor, with his tight black clothes contributing to the compositional effect.

5.12, right In Kriemhild’s Revenge, Marguerithe Schon’s wide-eyed stare, her heavy makeup, the abstract shapes in her costume, and the blank background create a stylized composition completely in keeping with the rest of the film.

Briefly for moments when the mise-en-scene elements align into eye-catching compositions. (Such compositions need not be wholly static. An actor’s dancelike movement may combine with a stylized shape in the set to create a visual pattern.)

Expressionist films had many tactics for blending the settings, costumes, figures, and lighting. These included the use of stylized surfaces, symmetry, distortion, and exaggeration and the juxtaposition of similar shapes.

Stylized surfaces might make disparate elements within the mise-en-scene seem similar. For example, Jane’s costumes in Caligari are painted with the same jagged lines as are the sets (see 5.2). In Siegfried, many shots are filled with a riot of decorative patterns (5.5). In The Golem, texture links the Golem to the distorted ghetto sets: both look as if they are made of clay (5.6).

Symmetry offers a way to combine actors, costumes, and sets so as to emphasize overall compositions. The Burgundian court in Siegfried (see 5.5) uses symmetry, as do scenes in most of Fritz Lang’s films of this period. Another striking instance occurs in Hans Wer-ckmeister’s Algol (5.7).

Perhaps the most obvious and pervasive trait of Expressionism is the use of distortion and exaggeration. In Expressionist films, houses are often pointed and twisted, chairs are tall, staircases are crooked and uneven (compare 5.8-5.10).

To modern viewers, performances in Expressionist films may look simply like extreme versions of silent-film acting. Yet Expressionist acting was deliberately exaggerated to match the style of the settings. In long shots, gestures could be dancelike as the actors moved in patterns dictated by the sets. Conrad Veidt “blend[s] himself into the represented milieu” in Caligari when he glides on tiptoe along a wall, his extended hand skimming its surface (5.11). Here, a tableau involves movement rather than a static composition.

This principle of exaggeration governed close-ups of the actors as well (5.12). In general, Expressionist actors worked against an effect of natural behavior, often moving jerkily, pausing, and then making sudden gestures. Such performances should be judged not by standards of realism but by how the actors’ behavior contributed to the overall mise-en-scene.

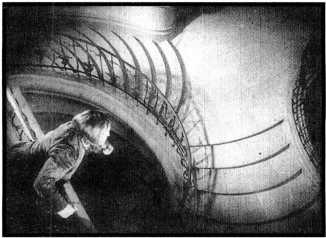

A crucial trait of Expressionist mise-en-scene is the juxtaposition of similar shapes within a composition. Along with Robert Wiene and Fritz Lang, F. W. Murnau was one of the major figures of German Expressionism,

5.13, left Count Orlak and his guest are placed within a nested set of four archways, with the hunched back of the vampire and the rounded arms of Hutter echoing the innermost arch. (Arches become an important motif in Nosferatu, associated closely with the vampire and his coffin.)

5.14, right In Murnau’s Tartuffe, the title character’s pompous walk is set off against the legs of a huge cast-iron lamp.

5.15, left A woman’s stance in Der steinere Reiter echoes the shape of the stylized tree behind her.

5.16, right In Nosferatu, the vampire creeps up the stairway toward the heroine, but we see only his shadow, huge and grotesque.

5.17 In Tartuffe, a high angle places an actor against a swirl of abstract lines created by a stairway.

Yet his films contain relatively few of the obviously artificial, exaggerated sets that we find in other films of this movement. He did create, however, numerous stylized compositions in which the figures blended in with their surroundings (5.13, 5.14). A common ploy in Expressionist films is to pose human figures beside distorted trees to create similar shapes (5.15).

For the most part, Expressionist films used simple lighting from the front and sides, illuminating the scene fatly and evenly to stress the links between the figures and the decor. In some notable cases, shadows were used to create additional distortion (5.16).

Although the main traits of Expressionist style come in the area of mise-en-scene, we can make a few generalizations about its typical use of other film techniques. Such techniques usually function unobtrusively to display the mise-en-scene to best advantage. Most editing is simple, drawing upon continuity devices like shot/reverse shot and crosscutting. In addition, German films are noted for having a somewhat slower pace than other films of this period. Certainly in the early twenties they have nothing comparable to the quick rhythmic editing of French Impressionism. This slower pace gives us time to scan the distinctive compositions created by the Expressionist visual style.

Similarly, the camerawork is typically functional rather than spectacular. Many Expressionist sets used false perspective to form an ideal composition when seen from a specific vantage point. Thus camera movement and high or low angles were relatively rare, and the camera tended to remain at a straight-on angle and an approximately eye-level or chest-level height. In a few cases, however, a camera angle could create a striking composition by juxtaposing actor and decor in an unusual way (5.17).

Like the French Impressionists, Expressionist filmmakers gravitated to certain types of narratives that suited the traits of the style. The movement’s first film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, used the story of a madman to motivate the unfamiliar Expressionist distortions for movie audiences. Because Caligari has remained the most famous Expressionist film, there is a lingering impression that the style was used mainly for conveying character subjectivity.

This was not the case in most films of the movement, however. Instead, Expressionism was often used for narratives that were set in the past or in exotic locales or that involved elements of fantasy or horror— genres that remained popular in Germany in the 1920s. Der Schatz takes place at an unspecified point in the past and concerns a search for a legendary treasure. The two feature-length parts of Die Nibelungen, Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge, are based on the national German epic and include a dragon and other magical elements in a medieval setting. Nosferatu is a vampire story set in the mid-nineteenth century, and in The Golem, the rabbi of the medieval ghetto in Prague animates a superhuman clay statue to defend the Jewish population against persecution. In a variant of this emphasis upon the past, the last major Expressionist film, Metropolis, is set in a futuristic city where the workers labor in huge underground factories and live in apartment blocks, all done in Expressionist style.

In keeping with this emphasis on remote ages and fantastic events, many Expressionist films have frame stories or self-contained stories embedded within the larger narrative structure. Nosferatu is supposedly told by the town historian of Bremen, where much of the action takes place. Within the narrative, the characters read books: the Book of the Vampires explains the basic premises of vampire behavior (exposition that would have been necessary, since this was the first of many vampire films), and entries in the log of the ship that carries Count Orlak to Bremen recount additional action. The central story of Warning Shadows (1923) consists of a shadow play that a showman puts on during a dinner party, with the shadow figures coming to life and acting out the guests’ secret passions. Tartuffe begins and ends with a frame story in which a young man tries to warn his aging father that the housekeeper is out to marry him for his money; his warning takes the form of a film of Moliere’s play Tartuffe, which constitutes the inner story.

Some Expressionist films do take place in the present. Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler uses Expressionist style to satirize the decadence of modern German society: the characters patronize drug and gambling dens in nightclubs with Expressionist decor, and one couple lives in a lavish house decorated in the same style. In Algol, a greedy industrialist receives supernatural aid from the mysterious star Algol and builds up an empire; the sets representing his factories and the star are Expressionist in style. Thus, in the cinema, Expressionism had the same potential for social comment that it did on the stage. In most cases, however, filmmakers used the style to create exotic and fantastic settings that were remote from contemporary reality.

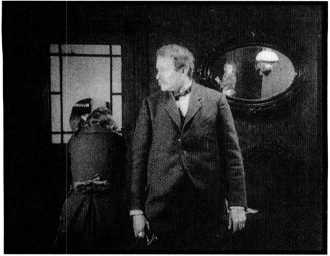

Another German trend of the early 1920s had less international influence but led to the creation of a number of major films. This was the Kammerspiel, or “chamber-drama” film. The name derives from a theater, the Kammerspiele, opened in 1906 by the major stage director Max Reinhardt to stage intimate dramas for small audiences. Few Kammerspiel films were made, but nearly all are classics: Lupu Pick’s Shattered (1921) and Sylvester (aka New Year’s Eve or St. Sylvester’s Eve, 1923), Leopold Jessner’s Backstairs (1921), Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924), and Carl Dreyer’s Michael (1924). Remarkably, all these films except Michael were scripted by the important scenarist Carl Mayer, who also coscripted The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and wrote other films, both Expressionist and non-Expressionist. Mayer is considered the main force behind the Kammerspiel genre.

In many ways these films contrasted sharply with Expressionist drama. A Kammerspiel film concentrated on a few characters and explored a crisis in their lives in detail. The emphasis was on slow, evocative acting and telling details, rather than extreme expressions of emotion. The chamber-drama atmosphere came from the use of a small number of settings and a concentration on character psychology rather than spectacle. Some Expressionist-style distortion might appear in the sets, but it typically suggested dreary surroundings rather than the fantasy or subjectivity of Expressionist films. (One Kammerspiel, Erdgeist, also scripted by Mayer and directed by Jessner, applied Expressionist sets and acting to an intimate, modern drama of lust and betrayal.) Indeed, the Kammerspiel avoided the fantasy and legendary elements so common in Expressionism; these were films set in everyday, contemporary surroundings, and they often covered a short span of time.

Sylvester takes place during a single evening in the life of a cafe owner. His mother visits his family for a New Year’s Eve celebration. Jealousies and conflicts between the mother and the wife intensify until, as midnight strikes, the man commits suicide. Brief scenes of people celebrating in hotels and in the streets create an ironic contrast with the tensions of these three characters, but most of the action occurs in the small apartment (5.18). As with most major Kammerspiel films, Sylvester uses no intertitles, depending on simple situations, details of acting and setting, and symbolism to convey the narrative events.

Similarly, Backstairs balances two settings. The boardinghouse kitchen in which the housekeeper works

5.18 In

Sylvester, a motif of shots using a mirror on the wall emphasizes the relationships among the characters within the family’s drab home.

5.19 Much of the action in Backstairs consists of the mailman’s trips back and forth across the courtyard as he visits the heroine.

And the apartment of her secret admirer, the mailman, stand opposite each other in a grubby courtyard (5.19). The film’s action never moves outside this area. When the heroine’s departed fiance mysteriously fails to write to her, the mailman tries to console her by forging letters from him. Finally she visits the mailman in his little apartment—at which point the fiance returns and is killed in a struggle with the mailman. The heroine then commits suicide by throwing herself into the courtyard from the top of the building.

As these examples suggest, the narratives of the Kammerspiel films concentrated on intensely psychological situations and concluded unhappily. Indeed, Shattered, Backstairs, and Sylvester all end with at least one violent death, and Michael closes with the death of its protagonist from illness. Because of the unhappy endings and claustrophobic atmospheres, these films intrigued mostly critics and highbrow audiences. Erich Pommer recognized this fact when he produced The Last Laugh, insisting that Mayer add a happy ending. This story of a hotel doorman who is demoted from his lofty post to that of lavatory attendant was to have concluded with the hero sitting in the rest room in despair, possibly dying. Mayer, upset at having to change what he saw as the logical outcome of his script’s situation, added a blatantly implausible final scene in which a sudden inheritance turns the doorman into a millionaire to whom all the hotel staff cater. Whether this ludicrously upbeat ending was the cause, The Last Laugh became the most successful and famous of the Kammerspiel films. By late 1924, however, the trend ceased to be a prominent genre in German filmmaking.

The historical spectacle, the Expressionist film, and the Kammerspiel drama helped the German industry break down prejudices abroad and gain a place on world film markets. Lubitsch’s Madame Dubarry was one of the first postwar German films to succeed abroad. It showed in major cities in Italy, Scandinavia, and other European countries in 1920, becoming famous even in countries like England and France, where exhibitors had pledged not to show German films for a lengthy period after the war. In December 1920, Madame Dubarry, retitled Passion, broke box-office records in a major New York theater and was released throughout the United States by one of the largest distributors, First National. Suddenly American film companies were clamoring to buy German films, though few found the success of Passion.

More surprisingly, German Expressionism also proved an export commodity. There was particularly strong anti-German sentiment in France. Yet The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari had an international reputation by late 1921 (having already had a mildly successful release in America after its triumph in Germany). In September, French critic and filmmaker Louis Delluc arranged for Caligari to be shown as part of a program to benefit the Red Cross. So great was the film’s impact that it opened in a regular Parisian cinema in April 1922. A fashion for German film followed. Works by Lubitsch, as well as virtually all the Expressionist and Kammerspiel films, played in France over the next five years. A similar fad for Expressionism hit Japan in the early twenties, and in many countries, these distinctive films had at least limited release in art houses.

World History

World History