The English and, after 1700, the Scots-Irish settlers of the tidewater parts of the Carolinas turned to agriculture as enthusiastically as had their Chesapeake neighbors. In substantial sections of what became North Carolina, tobacco flourished. In South Carolina, after two decades in which furs and cereals were the chief products, Madagascar rice was introduced in the low-lying coastal areas in 1696. It quickly proved its worth as a cash crop. By 1700 almost 100,000 pounds were being exported annually; by the eve of the Revolution rice exports from South Carolina and Georgia exceeded 65 million pounds a year.

Rice culture required water for flooding the fields. At first freshwater swamps were adapted to the crop, but by the middle of the eighteenth century the chief rice fields lay along the tidal rivers and inlets. Dikes and floodgates allowed fresh water to flow across the fields with the rising tide; when the tide fell, the gates closed automatically.

In the 1740s another cash crop, indigo, was introduced in South Carolina by Eliza Lucas, a plantation owner. Indigo did not compete with rice either for land or labor. It prospered on high ground and needed care in seasons when the slaves were not busy in the rice paddies. The British were delighted to have a new source of indigo because the blue dye was important in

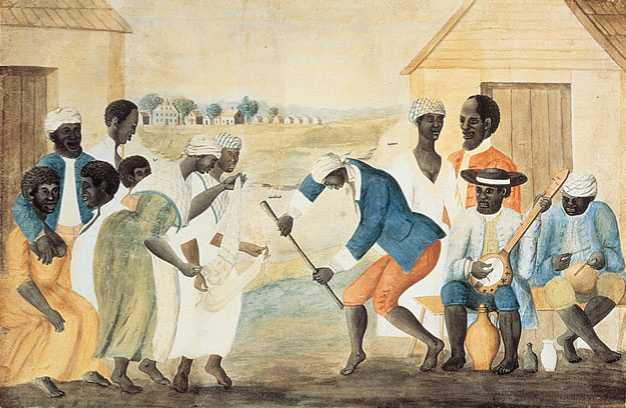

This depicts slaves on a South Carolina plantation, around 1790. Likely of Yoruba descent, they play West African instruments, such as the banjo, and also wear elaborate headgear, another Yoruba trait. But unlike their Yoruban contemporaries, who adorned faces and limbs with elaborate tattoos or scars, these slaves bear no evident body decorations. They are African, indisputably, but also American.

Their woolens industry. Parliament quickly placed a bounty—a bonus—on it to stimulate production.

Their tobacco, rice, and indigo, along with furs and forest products, meant that the southern colonies had no difficulty in obtaining manufactured articles from abroad. Planters dealt with agents in England and Scotland, called factors, who managed the sale of their crops, filled their orders for manufactures, and supplied them with credit. This was a great convenience but not necessarily an advantage, for it prevented the development of a diversified economy. Throughout the colonial era, while small-scale manufacturing developed rapidly in the North, it stagnated in the South.

Reliance on European middlemen also retarded the development of urban life. Until the rise of Baltimore in the 1750s, Charleston was the only city of importance in the entire South. But despite its rich export trade, its fine harbor, and the easy availability of excellent lumber, Charleston’s shipbuilding industry never remotely rivaled that of Boston, New York, or Philadelphia.

On the South Carolina rice plantations, slave labor predominated from the beginning, for free workers would not submit to the backbreaking and unhealthy regimen of cultivation. The first quarter of the eighteenth century saw an enormous influx of Africans into all the southern colonies. By 1730 roughly three out of every ten people south of Pennsylvania were black, and in South Carolina the blacks outnumbered the whites by two to one. “Carolina,” remarked a newcomer in 1737, “looks more like a negro country than like a country settled by white people.”

Given the existing race prejudice and the degrading impact of slavery, this demographic change had an enormous impact on life wherever African Americans were concentrated. In each colony regulations governing the behavior of blacks, both free and enslaved, increased in severity. The South Carolina Negro Act of 1740 denied slaves “freedom of movement, freedom of assembly, freedom to raise [their own] food, to earn money, to learn to read English.” The blacks had no civil rights under any of these codes, and punishments were sickeningly severe. For minor offenses whipping was common, and for serious crimes death by hanging or by being burned alive was practiced.

Slaves were sometimes castrated for sexual offenses—even for lewd talk about white women—or for repeated attempts to escape.

Although organized slave rebellions were infrequent, individual assaults by blacks on whites were common enough. (Personal violence was also common among whites, then and throughout American history.) But the masters had sound reasons for fearing their slaves; the particular viciousness of the system lay in the fact that oppression bred resentment, which in turn produced still greater oppression.

Thus the “peculiar institution” was fastened on America with economic, social, and psychic barbs. Ignorance and self-interest, lust for gold and for the flesh, primitive prejudices, and complex social and legal ties all combined to convince the whites that black slavery was not so much good as a fact of life.

World History

World History