In the spring of 1966, a middle-aged lawyer produced and directed a film about conditions at a Massachusetts hospital for the mentally ill. He filmed everyday activities as well as a show put on by the patients. The result, titled Titicut Follies after the patients' name for their show, was released in 1967 and set off a storm of protest. Since that directorial debut, controversy has pursued Wiseman through over thirty feature-length documentary films, In the process, his work has become emblematic of Direct Cinema.

Whereas the Drew unit concentrated upon situations of high drama and the Rouch-Morin approach to cinema verite emphasized interpersonal relations (see Chapter 21), Wiseman pursued another path, focusing on the mundane affairs of social institutions. His titles are indicative: Hospital (1970), Juvenile Court (1972), Welfare (1975), Sinai Field Mission (1978), Racetrack (1985). Law and Order (1969) records police routine, while The Store (1983) moves behind the scenes of a Dallas department store.

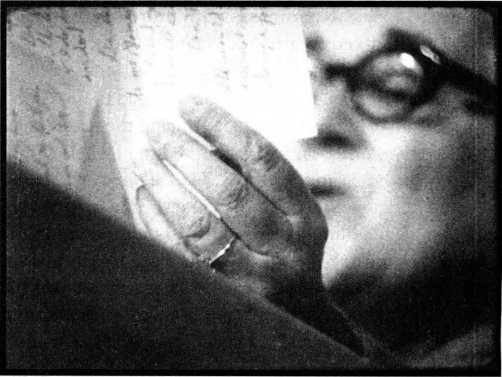

Wiseman typically does not follow individuals facing a crisis or solving a problem. He assembles a film out of slices of day-to-day life in a business or government agency. Each sequence is usually a short encounter that plays out a struggle or expresses the participants' emotional state, Then Wiseman moves to another situation and other participants. He has called this a "mosaic" structure, the result of assembling tiny pieces into a picture of an institution. Using no narrator, Wiseman creates implications by making shrewd juxtapositions between sequences and by repeating motifs across the film (24.2, 24.3). The meaning, he insists, is in the whole.

His first films reflect a conception of institutions as machines for social control. He declared himself interested in "the relationship between ideology and practice and the way power is exercised and decisions rationalized. Wiseman records the frustrations of ordinary people facing a bureaucracy, and he captures the insular complacency of those used to exercising power. In his most famous film, High School (1968), secondary education becomes a confrontation between bewildered students and oppressive or obtuse teachers: schooling as control and conformity.

In his later work, Wiseman claimed to take a more flexible and open-minded approach reminiscent of Richard Leacock's " uncontrolled cinema" (p. 483).

You start off with a little bromide or stereotype about how prison guards are supposed to behave or what cops are really like. You find that they don't match up to that image, that they're a lot more complicated. And the point of each film is

To make that discovery2

This concern for complexity, plus decades of support from the Public Broadcasting System (PBS), led Wiseman to expand his mosaics to vast proportions, shown as miniseries. Canal Zone (1977) runs almost three hours, the pair Deaf and Blind (both 1988) total eight hours, and Belfast, Maine (1999), a portrait of a community, lasts about six hours. It is as if his search for comprehensiveness and nuance forced Wiseman to amass more and more evidence, searching for all sides of the story. In later decades, Wiseman expanded his subject matter beyond micropolitical struggles for survival, investigating instead artistic creation in Ballet (1995; on the New York City Ballet) and La Comedie-Franr:;aise (1996). Despite Wiseman's increasing emphasis on television, his films are also shown in museums and in marathon retrospectives at film festivals.

24.2, 24.3 The controlling hand as a motif in High School.

(continued)

World History

World History

![United States Army in WWII - Europe - The Ardennes Battle of the Bulge [Illustrated Edition]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432563079_1428528748_0034497d_medium.jpeg)