This quiet stretch of riverbank contains remnants of Thonburi’s original communities along with temples, shrines, mosques and churches, and even a pagoda that affords a magnificent view. Duration: 3 hours

The reason why the Wong Wian Yai terminus of the Mahachai-Mae Klong railway is such a modest little affair is that it was never actually built as a terminus. It was originally the penultimate station, with the line tootling on towards the river and terminating at Klong San ferry pier. From here, the produce was loaded onto boats and floated straight over to the piers that served the commercial heart of the city, which in those days was Charoen Krung Road and Chinatown. The railway had been built and operated under a forty-year concession by the Tha Cheen Railway Company, headed by Celestino Xavier, one of the most influential members of the Portuguese community in Bangkok, who served at the Siamese ministry of foreign affairs and was awarded the title Phraya Phiphat Kosa. When the concession expired in the early 1940s, the line was bought by the government and eventually became part of the State Railway of Thailand. In 1961, the traffic around the Klong San-Wong Wian Yai area having become congested, military dictator Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat decided to axe the section of line that ran through the increasingly busy streets. He had wanted to cut the line a few stops down, at Wat Singh, but the residents and traders persuaded him that Wong Wian Yai would be more appropriate.

Today, crossing over Somdet Phra Chao Taksin Road from the Wong Wian Yai terminus, it can immediately be seen where the railway line used to run, for concrete slabs have simply been laid over the course of the track. On the corner of Charoen Rat Road, along which the line had passed, is one of Bangkok’s leading leather markets. Further along this road there are some attractive old houses, one of them being home to the Thonburi Full Gospel Church, a conspicuous pink landmark with a huge red cross on its frontage. Keep walking, following the ghost of the line, and Klong San Market comes into view. At first sight this looks like any other small urban market in Bangkok, but look a little closer and it becomes apparent the market has been laid out exactly on the site of the old Klong San station, and consequently has a long, linear footprint. Although there is a wet market off to the left, the main attraction is the garment market, which occupies the site of the line and the platforms, and is one of the best-known markets for young Thais to shop for inexpensive fashion. Klong San is, for compulsive non-shoppers (I think you know who I mean), a rather tedious market to negotiate, because much of the thoroughfare is a single alley: you go up and you come down the same way. At the end of the market, next to the steps that lead up to the river pier, there is a long, single-storey timber building that housed the ticket office.

Klong San is today an almost forgotten corner of Bangkok, important only to those who live here or the ferry passengers passing through. But in the days of Ayutthaya and subsequently the Thonburi kingdom, the entire bank of the river, starting from here, was the port where the ships moored to offload their produce onto smaller vessels or into warehouses, and for the captains to pay their taxes and tea money. This continued into the Rattanakosin era, with the old harbour busy with the produce of the rice mills and timber yards located along the Thonburi bank, and remnants can be found today. Turn northwards at Klong San Market, and an enormous marine mast can be seen towering above the rooftops.

When Rama iv built the third and final moat around Bangkok, he ordered the construction of five forts along the canal and also the building of a fort on the Thonburi bank, thereby forming a strong line of defence against any sea-borne invasion. Pong Patchamit Fort was built at the inlet of the San canal, the waterway from which the district derives its name, and it was directly opposite to the fort on the opposite bank that guarded the entrance to the new moat. Three years later, in 1855, the Bowring Treaty was signed and Siam opened to foreign trade. Steam ships began replacing Chinese junks and foreign shipping began to crowd into the harbour. In the reign of Rama v, the Harbour Department installed a signal flagpole at Pong Patchamit Fort where flags were hoisted to indicate the owners of the trading vessels that were arriving or departing. During Rama vi’s reign the signal flag was moved downriver to Klong Toei, and the flagpole at the fort was changed to indicate weather conditions that were provided by the Meteorological Department. Later, when the weather forecasting system was modernised, the signal flag method ceased. The mast however remains, as does part of the fort. The Fine Arts Department rescued what was left in 1949. Unless the visitor knows it is there, he or she will never find it, because the fort is hidden away behind the Klong San District Office. Enter Soi Lat Ya 21, the lane beside the mast, and walk through the District Office compound. There is a flight of steps leading up to the ramparts, and a small garden with stone seats.

On the other side of the mast is the Taksin Hospital, and the lane alongside here, Soi Lat Ya 17, leads between old timbered houses to a tiny canal. On its bank is Wat Thong Noppakhun, a temple of unknown age, in whose forecourt is a stone yannawa, an ocean-going Chinese ship. About seven metres long, painted cream and red, and with a bodhi tree for a mast, the vessel carries an inscription in Thai that commemorates the arrival of Buddhist monks from China and Japan. The vessel is a shrine, with offerings made at the base of the tree, and directly behind the rudder is a single Chinese grave, encased in plaster, where offerings are also made. The temple is believed to pre-date the Bangkok era but to have been restored during the reign of Rama ii, the Chinese porcelain on the gable ends of the wiharn having become popular then, signifying the scale of trade with China. Inside the wiharn are murals, with depictions of Siamese cats perched above the main doorway, on guard against mice, cockroaches and other vermin. The windows on the temple ubosot, or ordination hall, are unlike any other, resembling the port-holes of a ship, set deep within the thick white walls, protected by gold and lacquer shutters and ringed by elaborate frames. The sema stones, used to mark the sacred area of an ubosot, are encased in cylindrical columns looking rather like miniature lighthouses, with the stones visible only through a small slot on either side. Several chedis surround the temple, and there are many small chedis and grave markers outside the house of the abbot, beyond which can be seen a Chinese pagoda rearing into the sky.

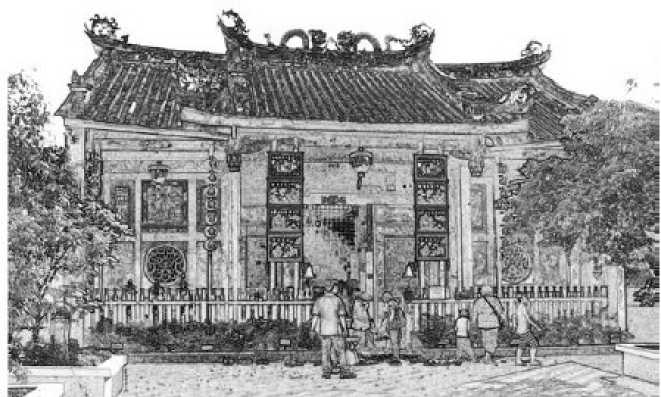

Follow the lane around past the front of Wat Thong Noppakhun and some of the most exuberant Chinese architecture in Bangkok will be revealed. Chee Chin Khor was a society formed in 1952 to undertake charitable works for the poor and to provide disaster relief supplies. During the first forty years of its existence the society headquarters had a rather peripatetic existence, but this riverside site became home in 1993. A temple was built, a four-storey structure with multiple roofs clad in green ceramic tiling, and the pagoda was added as recently as 2001, becoming an instant landmark for river travellers. Saturday morning is a good time to visit Chee Chin Khor Temple, as there is a service at that time and a sizeable crowd gathers at the open-air restaurant at the side of the compound. There are four altars within the temple, with fat Chinese Buddhas and gongs and incense, and the crowd surges into the building to disperse amongst the various floors and altars. A climb up the circular interior staircase of the pagoda is irresistible, and from the top there are beautifial views of the river and the city.

The towering stupas and prang of Wat Phichaya, built with materials from China.

From here, too, is a view of Wang Lee Mansion, one of the few remaining walled Chinese courtyard houses that were once a feature of Thonburi and Bangkok. Wang Lee Mansion is not open to the public, and in fact is still a residence and a company compound. There is no alley through from Chee Chin Khor to the imposing gate of the mansion, so a return to Somdet Chao Phraya Road is necessary before entering the neighbouring Chiang Mai Road. The road is short and runs directly down to what was a harbour known as Huay Chun Long, which means “Steam Boat Pier”. There is a shrine here to the goddess Mae Tuptim, where Chinese sailors would pray for a safe passage across the ocean. Chinese operas are still performed from time to time in front of the shrine. On both sides of the road are godowns and shophouses belonging to Chinese merchants, and the entrance to the Wang Lee compound is busy with trucks and pickups. Tan Chu Huang, the founder of the Wang Lee business, was an immigrant from Shantou who arrived in Bangkok in 1871. He established a business in rice trading and milling, which eventually was to become one of the largest of its kind, with a rice mill here next to the pier and another four further downstream. Following his marriage to a Siamese lady of Chinese descent, he built Wang Lee Mansion beside the harbour in 1881. Designed in a U-shape around a central courtyard paved with flagstones brought from China as ballast, the house is still in the hands of the same family, and has recently been carefully restored.

Opposite to the Wang Lee Mansion is a lane leading to Wat Thong Thammachat, an Ayutthaya-era temple in a woodland glade that seems far removed from the booming traffic, despite being only five minutes away from the main road. The ubosot, with its neat red window frames and its neat red fence, sits in a well-tended courtyard with a red meeting hall behind. The lane will take the visitors round behind the temple, through a small area of old houses, and back out to Somdet Chao Phraya Road. Little can have changed in this locality over the past century.

A long, straight canal, Klong Somdet Chao Phraya, runs alongside this road. Appearing on late nineteenth century maps as Regent Canal, it led directly to a small island on which were three palaces, one of them belonging to Dit Bunnag, who had acted as regent for Rama IV and who was elevated to Somdet Chao Phraya, the highest title a commoner could attain, equal to royalty. Only the king and the king’s brother, who was appointed “second king”, a position invented by Rama IV but later discontinued, were higher. Alongside this canal too were mansions and even a zoological garden. One of the canal-side mansions belonged to another member of the Bunnag family, who were descended from a Persian merchant who had settled in Ayutthaya around the year 1600. Built in the last years of Rama iv’s reign, the two-storey mansion is a romantic blend of English Tudor and Moorish. When the Somdet Chao Phraya Hospital was built nearby, an annex for the psychiatric unit was built next to the mansion, and the old house taken over as the residence for the hospital director. Today, beautifiolly conserved, it acts as the hospital reception, while on the second floor is the Institute of Psychiatry Museum. Alas, Regent Island is no more the home of palaces: the surrounding canal was filled in to become Arun Amarin Road, and although there are a couple of gracious old houses behind high walls, the island is now fringed with standard mid-twentieth-century housing.

Not far from Regent Island and on the bank of the Somdet Chao Phraya canal is a glorious riot of white stupas. This is Wat Phichaya Yatikaram, an Ayutthaya-era temple that was greatly enlarged during the years 1829-1832, in the time of Rama lll, by Tat Bunnag, the brother of Dit. The two brothers were so powerful in the court of Siam that they were known as the Sun and the Moon, and Tat also took the title of Somdet Chao Phraya. The temple architecture is heavily influenced by Chinese style, very much a characteristic of Rama iii’s reign, when almost all of Siam’s trade was with China. The Bunnags owned junks, and most of the materials used in the construction of the temple were brought in from China, including the boundary stones that were carved by Chinese stoneworkers. Instead of the overlapping roof leaves and the finials of the traditional Siamese temple, the roof of the ubosot resembles the hood of a Chinese carriage, and the eaves are decorated with stucco flowers and dragons. At the main entrance of the ubosot is a painting of a Chinese warrior with a lion at his feet, a theme that is repeated on another door, where a dagger-wielding angel is subduing a lion. Two enormous white prangs tower over the compound, the largest of them housing four Buddha images looking out towards each of the cardinal directions. A bronze statue of Tat Bunnag is seated at the temple entrance, looking across the canal towards the river, the face modelled after a photograph taken of him in middle age.

A few years later, in 1850, Tat Bunnag completed Wat Anongkharam, on the opposite side of the road. The architectural style here is very different, the wiharn being built in the classic early Bangkok style that originated in the time of Rama I. The principal Buddha image, Phra Chunlanak, is from Sukhothai although it was installed as recently as 1949, a century after the temple was built. The image is in the “Subduing Mara” position, conquering evil, the right hand over the knee, the fingers touching the ground, the left hand remaining palm up in the lap. There are other Buddha images in the crowded temple compound, which also includes a school.

Wander down the quiet little lane that runs beside Wat Anongkharam, heading towards the river, and in this neglected corner of Klong San once lived the most famous of the temple school’s former pupils. The late Princess Srinagarindra, the Princess Mother, who was born in 1900 and passed away in 1995, was the mother of two kings: Rama XIII, who became king in 1935 at the age of nine, and died in mysterious circumstances in 1946, and King Bhumibol Adulyadej, Rama IX. Yet she was born a commoner, the child of a Chinese father and a Siamese mother, and she grew up on this very street, attending what was then the all-girls school at Wat

Anongkharam, founded by an enlightened abbot who believed in the need for girls to have an education, not a generally accepted practice at that time. Her father was a goldsmith and the family lived in a modest rented house. In those days when Siamese were not required to have family names, the young girl was simply known as Sangwan. She went on to study nursing at Siriraj Hospital, further along the riverbank, and after graduating she was one of only two girls in that year to win a scholarship to study nursing in America. It was in the United States that she met Prince Mahidol, the sixty-ninth son of Rama V, who was studying medicine at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The couple later returned to Siam, where the prince worked to form a public health system, but he died young, passing away at Sra Pathum Palace in 1929. In 1993, shortly before his mother’s death, King Bhumibol made known his wish to renovate the area around the Princess Mother’s childhood home to provide a public park. Her family home no longer existed but there were some similar buildings nearby, which the owners gladly donated. The Princess Mother Memorial Park is a lovely, leafy area of some one-and-a-half acres, sheltered by tall trees and with fragments of walls and crumbling arches embedded amongst the greenery. There are two house-sized exhibition halls, which display photographs and mementos from the Princess Mother’s life, and there is a reconstruction of her childhood home. This plot of land had once held the mansion home of another member of the Bunnag family, Pae Bunnag, who had been director general of the Royal Cargo Department during the reign of Rama V. Part of his kitchens still exist, now forming the Pae Bunnag Art Centre at the back of the park. To one side of the park, seated on a bench, is a life-size bronze statue of the Princess Mother, gazing across the greenery.

Leave the park by the rear gate and there is a small patch of wasteland and, behind that, sitting directly on the riverbank, one of Bangkok’s most florid Chinese shrines. Gong Wu Shrine has a long history, predating Bangkok and even predating the Taksin era. There are three statues here of Gong Wu. The smallest was brought to Siam by Hokkien traders around the year 1736, during the period of the Qing Dynasty Emperor Chen Long. Later, in 1802, the second Gong Wu statue arrived, and in 1822 a wealthy Chinese named Kung Seng renovated the shrine, installed a bell tower, and brought in a third statue. The Gong Wu Shrine has its own jetty, and from the end of this can be seen a small green onion-shaped dome at a neighbouring jetty. There is a small public garden between the two jetties, so the only way to find out what the dome belongs to is to walk around the garden and into a rather dusty little corner, where through an almost hidden gate is the courtyard of the Goowatin Mosque. This is, however, a very unusual mosque. The dome is mounted over the jetty, and the only indication that this tiny building is a place of worship is the traditional row of taps outside for the washing of hands and feet. Originally the building had belonged to (yes, you have guessed correctly), Tat Bunnag. It had been used as a warehouse, and next door, boarded up and crumbling away, is a splendid colonnaded building that must have been the offices. The Persian ancestor of the Bunnags, Sheikh Ahmad, had been a Muslim, and many of his descendants had held high office for Islamic affairs in Siam. The Bunnag line had become Buddhist, but clearly there were strong family connections because when a group of Muslims arrived from the Indian city of Surat in the time of Rama IV, Tat Bunnag had handed over this property for them to use as a mosque. The Indians were traders but some became skilled translators in the Bunnag business. One of them was named Ali Bai Nana. Everyone knew him as Clerk Ali, but he had ambitions beyond translating, and he rose to become one of the wealthiest members of the Indian community, the founder of the powerful Nana family. His descendant Lek Nana owned part of the land on which the Princess Mother Memorial Park was laid out, and the family today own huge plots of land on Sukhumvit Road, where the name is given to the district that is served by the bts Skytrain Nana station.

Crossing a bridge over the small canal that runs through here to

Connect with Klong Somdet Chao Phraya takes us under the concrete span of Pokklao Bridge to, just a few metres further on, the green girders of the far more aesthetically pleasing Memorial Bridge. Opened in April 1932, the name commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Chakri dynasty, although in Thai it is simply named after Rama I, King Buddha Yodfa, and is known as Saphan Phra Phutta Yodfa, or colloquially, Saphan Phut. The designers and builders were a British company, Dorman Long, who also built Sydney Harbour Bridge and who remain in business to this day Work began on 3 rd December 1929. A riveted steel truss structure, using 1,100 tons of structural steel, the bridge has three spans. The two outer spans, each of 74.9 metres (246 ft), are fixed. The centre span, measuring 61.8 metres (202 ft 11 ins) and 7.3 metres (24 ft) above the water at its highest point, is a bascule span, composed of two separate parts, each of which could originally be tilted upwards to allow tall vessels or ceremonial river processions to pass underneath. The bascule arms turned on fixed trunnions and were balanced by 450-ton cast-iron weights hanging inside concrete piers on both sides of the river. An electric motor operating the gearing could raise the two bascule leaves in less than five minutes, and a petrol engine was on standby in case the power supply failed. The operator sat in a cabin on the east pier, with an electrical cable on the riverbed connecting the gearing in each pier. Another cabin was located on the opposite bank for the sake of design symmetry, but the only mechanism controlled from there was the safety locking gear. Sadly, this ingenious mechanism, designed by a British engineer named Frederick Thompson and manufactured by Thomas Broadbent and Sons of Huddersfield, is no longer in use. When the Pokklao Bridge was being built in 1983, ending the possibility of tall ships sailing any further upriver, the two bascule sections were permanently connected and hold-down tendons and bearings installed to dampen any movement. As the entire lifting gear is contained inside the piers and is not visible from the shore or the river, the curious-minded, strolling along the pedestrian walkway to try and

See how the mechanism worked, will find little to enlighten him.

At the foot of the bridge is Wong Wian Lek, the smaller of the two Thonburi traffc circles. Or at least, this is where it used to be. With the opening of the Pokklao Bridge and its access roads, the circle was cut in two and its landmark clock tower moved east towards Somdet Chao Phraya Road, where there is still the Wong Wian Lek Market. From here operated a bus service over the bridge to business areas such as Chinatown and the Indian district of Pahurat. The terraced houses alongside the road connecting to the bridge were of two storeys, with a tin roof, and many of them survive today. In the vicinity of the circle there were shops and parking areas for horse-drawn carriages and cycle rickshaws waiting to take people over to the Bangkok side. The food shops along the footpath meant that the area was a busy and colourful one, especially at night. In the years between the opening of the bridge and the start of World War ii., bands played here on Saturday and Sunday evenings and the circle, with its buses bringing in passengers and moving them out, must have been very pleasant, especially compared to the impersonal roar of today’s traffic over the bridge. Wong Wian Lek Market, however, still retains its garden atmosphere and is a noted place to buy Buddha amulets, while on the other side of the bridge approach road there is a small and pretty garden ringed all the way round by a handsome wrought-iron fence painted in fire-engine red.

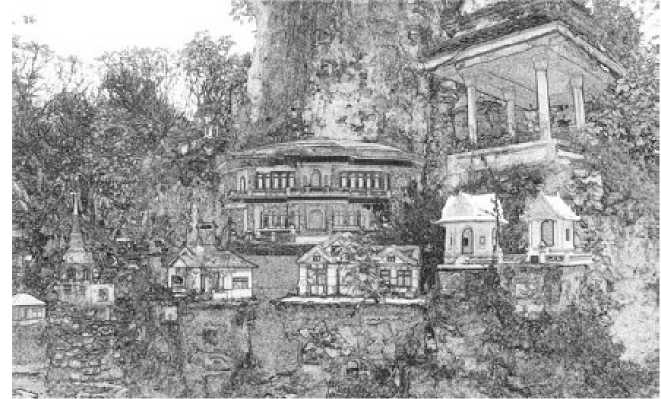

Miniature mansions for the departed, set into the candle-wax mountain at Wat Prayoon.

Take a closer look at this fence, and it is seen to be fashioned in the shape of lances and arrows and that its arched sections bristle with axes and swords. The fence was ordered from Britain in the time of Rama iii, the payment being in sugar cane equal to the weight of the fence, and it was originally for part of the Grand Palace. The king, however, decided he didn’t want it. That left the minister of the treasury, Dit Bunnag, with an awful lot of fence. He was, however, building a temple on land he had previously used as a coffee plantation, and when Wat Prayoon was completed a home was found for the fencing. There was so much of the stuff that it was used to enclose the entire compound, and the locals were quick to dub the temple Wat Rua Lek, or Iron Fence Temple. When the Memorial Bridge was built a slip road was cut through the compound and this distinctly un-Buddhist design was partly replaced with a less militant fence for the temple entrance, although there is a remnant leading from the gateway to the pagoda, an enormous white structure that towers 61 metres (200 ft) and forms a clearly visible landmark from the opposite side of the river. Designed in the shape of a bell, Wat Prayoon’s pagoda was the first in Bangkok to be built in Sri Lankan style. The interior fencing divides the temple grounds into two distinct halves. The buildings on the south side are all in traditional Thai style. In the ordination hall can be found a 5.79 metre (19 ft) tall Buddha image named Phra Buddha Nak, which was brought to Wat Prayoon from a temple in Sukhothai in 1831, and which is one of a pair, the other being in Wat Suthat Thepwararam on the other side of the river. The buildings on the north side of the iron fence are mostly in Western architectural styles, including a single-storey structure with beautiful stained-glass windows that was built in 1885 as a gathering place for members of the Bunnag family. Monks and novices also used the building for studying the Dharma, but in 1916 the Thammakan Ministry, the forerunner of the Ministry of Education, changed it into a public reading room, and it thereby became the first public library in Thailand.

In the temple grounds is a monument depicting three up-ended cannons, built to commemorate a huge gunpowder explosion during the fireworks display staged to mark the temple’s official opening on 13th January 1837. Dr Dan Beach Bradley, one of the first Protestant missionaries allowed to work in Bangkok, recorded that thousands of people had turned out to watch and that many injuries were caused when a cannon exploded. Bradley, who was a medical doctor, was summoned to treat a monk’s injured arm, amputating it at the shoulder in what was the first case of a Western surgical procedure used during this era. Possibly it was the fireworks accident that led to the twenty-six large octagonal water basins, bearing various designs such as dragons, trees, bamboo and flowers, that were imported from China and installed around the pagoda. Similar basins can be found at the ancient royal palace of Gu Gong in Beijing, where they were intended for extinguishing fires, rather than sacred purposes. The lion figures were also brought from China. If you see children trying to pull the crystal ball out of the male lion’s mouth, it is because they have been told that if they can do so, the ball will turn to pure gold. For all its other distinguished qualities, Wat Prayoon is best known for a whimsical structure tucked into the corner of the grounds nearest the river, where it can be found by passing under an arch bearing the name Khao Mor, or Mor Mountain. Inside this enclosure is a pond with fish and turtles, and rising out of the water is an artificial mountain that was designed by Dit Bunnag to resemble the wax of a melting candle. The mountain is a shrine, with caves and niches occupied by Buddha images and miniature buildings, along with monuments to the departed. A set of steps leads to the top of the mountain where a bronze pagoda is situated. Locals call this place Turtle Mountain, and bring their families to feed banana and papaya to the turtles.

The Portuguese had been the first Europeans to settle in Siam, arriving in Ayutthaya shortly after they captured Malacca in 1511, shrewdly dispatching an envoy to the king beforehand to reassure him that they had no territorial ambitions. In 1516, Portugal signed a treaty with Siam to supply firearms and munitions, and with the treaty came the rights to reside, trade and practice their religion in the country. This brought the first Portuguese friars in 1567, and they established the Catholic Church in Ayutthaya. After the fall of Ayutthaya, the Portuguese continued with their military support of Taksin in his efforts to drive the Burmese out of Siam, and the supply of cannon and muskets contributed significantly to the strength of Taksin’s army. With Thonburi as the new capital, the king, in recognition of their services, presented the Portuguese with an area of land on the riverbank and granted them permission to build a church. He visited this community himself on 14th September 1769. A wooden church was completed the following year, and as 14 th September marks the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross, the church was named Santa Cruz, or Holy Cross. Taksin was also encouraging Chinese immigrants to settle in the adjacent area of land, which was quickly becoming heavily populated, and when in 1835 a new church was built to replace the wooden structure it was designed in a Chinese style. The church became known to residents as Kudi Cheen, or Chinese Church, the term kudi meaning “an abode for priests or monks”, and the name became attached to the entire neighbourhood, and even to the foreign residents, who were known as '“farang Kudi Cheen”. The Chinese Church lasted for less than a century, and in 1916 the third and present version of Santa Cruz was built. This time the design was by two Italian architects, Annibale Rigotti and Mario Tamagno, and with its characteristic octagonal dome and classical proportions is resolutely Italianate in style. The name Kudi Cheen, however, remains firmly in usage, for both the church and for the neighbourhood.

Santa Cruz is only a few minutes’ walk from the Memorial Bridge via the attractive walkway that has been built along the riverbank in recent years. An equally picturesque entry can be made by ferry from Pak Klong Talat, the flower market on the other side of the river, for the church has its own pier. The neighbourhood is quiet and neat, and the church precincts are almost silent. Unless your visit is at a time of worship the only other visitors are likely to be local residents passing through on their way to and from the river. During school hours the voices of children can be heard from the Santa Cruz Suksa School and Santa Cruz Convent, and nuns can sometimes be seen flitting through the precinct, but otherwise the visitor is alone. A number of statues stand in the grounds, including one of Mary set in a garden grotto near the river, and there is a large crucifix next to the pier. Santa Cruz Church is painted in delicate pastels of cream and red ochre, with stained glass fanlights above the windows. The roof is a barrel vault structure, and there is a classic pediment and Italian frescoes over the altar. A handsome two-storey presbytery stands on one side of the precinct, and to the rear of the church, away from the river, there is a tiny cemetery with the graves of former pastors.

Thonburi, of course, was short-lived. In 1786, four years after Bangkok was established as the capital, King Rama I granted the

Portuguese land on the riverbank at Chinatown, and here they built Holy Rosary Church. Their influence was nonetheless dwindling, especially in religious work where French missionaries largely eclipsed them during the nineteenth century. Santa Cruz Convent, for example, was founded by the Sisters of Saint Paul of Chartres, a French order, in 1906.

The Portuguese have, however, left behind a very tangible legacy. The Thais had not known the art of baking until the Portuguese settled in Ayutthaya, and indeed the Thai word for bread, pung., comes from a word for bread used by the Portuguese at that time. The Kudi Cheen community baked their own bread and cakes, and today there are still bakeries here producing a sponge cake known as khanom farang Kudi Cheen, using apple and jujube and made to the same recipe used in the time of the Portuguese merchants and priests who had thrived in Ayutthaya. The largest bakery is located directly to one side of the precinct, entered via an unmarked doorway set between a statue of Jesus as the Good Shepherd and a modern three-storey house that is only one room wide. No one appears to mind if you wander inside. There are a handful of women putting the mix and fruit into star-shaped moulds, while the baking is done by a man who places the moulds in a tandoor-like oven and then puts a tray over the top, which he heaps with glowing coals. The baking done, the cakes are packed into cellophane bags and every so often a bicycle-powered cart will depart from the premises and deliver them to shops in the locality.

The Kudi Cheen houses in the vicinity of Santa Cruz are smart and have a prosperous air about them, and as there are no roads here, only footpaths, there is an agreeably sleepy atmosphere. This is still very much a Catholic community, even though the blood of those Portuguese settlers has long since mingled with Thai and Chinese blood, and Christian images can be seen on the houses and fences. Each of the tiny lanes is neatly numbered, although many are cul de sacs, and charting a way through the maze is not easy Soon, though, the path emerges onto the riverside walkway. There is an intriguing old house here that looks as if it has been abandoned for many years, but in fact is still occupied, after a fashion. Standing on church land, the house is constructed of golden teak and is founded upon a solid stone platform, which has protected it from the waterlogged ground. Faded and blackened with age, its shutters firmly closed, its front door occasionally open to allow the river breezes to blow through, this is Windsor House, or Baan Windsor, a classic example of the gingerbread style that is known as Ruen Manila. Louis Windsor, a wealthy British merchant who had settled in Bangkok during the reign of King Rama IV and who married a Thai woman, Somboon, built the house. Their home was passed down the generations to the modern-day Jutayothin family, who leased it to expatriates during World War II and have ever since lived in a nearby residence, leaving caretakers in place. There has been a recent move to register Windsor House with the Fine Arts Department and turn it into a museum for the Kudi Cheen area.

The riverside shrine to Kuan Yin is in a classic Chinese design.

A few metres along the walkway the Catholic community ends at a small waterway and the Chinese district begins. Taksin had encouraged the Hokkien Chinese to settle here. Residents had originally built two shrines on this site, but during the reign of Rama iii the shrines were pulled down and replaced with a single temple to the goddess of mercy, Kuan Yin. Over the course of a number of years the temple fell into a state of dilapidation until the reign of Rama V, when one of Siam’s best-known historians, Prince Damrong Rachanuphap, passed through the community on his way to neighbouring Wat Kanlayanamit to take part in the casting of a large bell. He noted the decayed condition of the building, the cracking of the mural paintings, the deterioration of the carvings on the roof, and the depredations of rain and bats, and he urged the conservation of the temple that was, he said, a masterpiece created by skilled artists who even then were becoming hard to find. Today, the temple remains faded on the exterior, although a bright red archway has recently been added at the walkway, leading through to a red-tiled courtyard. Two dragons writhe on the roof. There are some beautifiol bas-reliefs and murals on the exterior walls, framed in blue, but they have become weathered and much of the paint has disappeared. Inside, seen through swirling clouds of incense smoke, the wall paintings are vivid, traditional golden silk lanterns hang from the roof beams, and a one-metre-high statue of Kuan Yin sits serenely at the back of the altar, facing the river. The shrine is cared for by a local family and has a steady stream of Chinese visitors, albeit ones with a tendency to become somewhat agitated when a large foreigner hoves into view with a camera.

From the walkway of the Memorial Bridge, Wat Kanlayanamit, an enormous barn-like structure that rises above the neighbouring rooftops, dominates this part of the riverbank. Oddly, though, it is easy to walk straight past the entrance when following the riverside pathway, because it is an unassuming one next to a clutter of wooden shops and eating houses, and the temple is set further back from the river than it appears from a distance. Passing through the gate one is within another distinctive aspect of the Chinese community. A Chinese nobleman named Toh Kanlayanamit, who owned a residence on this piece of land, founded Wat Kanlayanamit in 1825 and the design is a blending of Chinese and Thai styles. At the river entrance are two Chinese pavilions, built from brick and encased in mortar to give the appearance of stone, and next to the small wiharn to the rear of the compound is a Chinese chedi. On the other side of the wiharn is an elegant bell tower housing the giant bell, the biggest bronze bell in Thailand, which Prince Damrong had watched being cast. Inside the wiharn are murals dating from the founding of the temple. The gable of the ubosot is Chinese in style, the distinction being the lack of finials and overhanging eaves, and a floral design covers the flat gable frontage. The ubosot also has murals depicting life from the time of Rama iii, but parts of them are sadly deteriorated. Beneath the floor is reportedly the basement of Toh Kanlayanamit’s house. Wat Kanlayanamit is a second grade royal temple, and it is the royal wiharn, the hall of worship, that towers over the compound. The reason for its great size soon becomes clear, for the wiharn was built to house a huge Buddha image, 15.2 metres (50 ft) high and 11.6 metres (38 ft) wide, which almost fills the entire structure. Fashioned after a Buddha figure in Ayutthaya, the image is named Samporkong, and attracts crowds of Chinese devotees during the Chinese New Year period.

Leaving Wat Kanlayanamit by the side gate takes us straight to the bank of Bangkok Yai canal, where one will see the lock gate used to control the water flow, and envy the gatekeeper who has a cosy little office on top of the structure. Following the pathway will take us to Arun Amarin Road. Cross over here, following the narrow waterway that runs briefly alongside Bangkok Yai, and we are in another distinctive community in this most ethnically diverse of districts, for this is Kudi Khao, one of the oldest Muslim communities in Bangkok. Three religions—Christian, Buddhist and Muslim—live peaceably

Together in an area that can be traversed on foot within half an hour.

The Muslims of Kudi Khao are Sunnis. They are Cham in origin, whose ancestors migrated from Borneo, some going into Vietnam and Cambodia, and others finding their way to Ayutthaya, where they became traders and farmers, living on rafts on the rivers and canals of the capital. Early settlers had also made their homes on the Bangkok Yai canal, and when Thonburi was founded more made their way down the Chao Phraya to join them. The largest community formed on the north bank, around the Tonson Mosque, but others settled here on the south bank, where in the time of Rama I they built their own mosque, officially Bang Luang Mosque, taking its name from the early name for the canal, but usually referred to as Kudi Khao: the word khao meaning “white”. There are no roads in this tiny community, only narrow pathways built around the course of the waterway, which forms the shape of a square and which is worryingly unguarded for much of its length. Kudi Khao is in the centre of this maze of timber houses, in a small clearing of residences and shops and so tightly hemmed in that the thoroughfare is only a few metres wide. This is no conventional mosque for at first glance it could easily be mistaken for a Thai temple, the architectural form following the traditional Thai style. The structure is entirely white, except for the roof, whose tiles are of an Islamic green. Closer examination reveals the symbol of Islam on the gable, adorned with Chinese-style stucco flowers. Thirty pillars support the structure, signifying the thirty principles of the Koran, while the twelve windows and one door represent the thirteen principles of daily prayer. On the north side of the mosque is a timber sala, or pavilion, serving as a gathering place for community members. The only mosque in Bangkok built to this style, Kudi Khao is an architectural gem that draws Muslim visitors from throughout Asia.

It is possible for the most adventurous of us to chart a way through the back lanes from Kudi Khao into another of Thonburi’s oldest communities, for Bang Sai Gai is only a few minutes away on foot, and the campus of Bansomdej Chao Phraya Rajabhat University is the main landmark. We are, however, looking for a village within this village, and it can be found along Itsaraphap 15, alongside the university, where there is a roadside shrine and, quite possibly, the sounds of someone down the tiny alley opposite tootling an experimental tune on a flute. Ban Lao is a settlement that has its origins in the time of King Taksin. One of his first campaigns was against a rebellion in Vientiane, and he had sent General Chakri there to bring back the Emerald Buddha, which had been taken by Lao invaders from its Chiang Mai temple two hundred years before. The soldiers stormed Vientiane and along with the holy image they brought back with them a considerable number of prisoners of war. Some of the Lao were skilled in the ancient craft of making flutes from bamboo. They settled in this little area near the canal junction and their ancestors remain here to this day, still making their flutes. I had last entered this little alley, or trok, a dozen years previously when I met the patriarch of Ban Lao, Jarin Glinbuppha. Jarin passed away a few years ago, and his daughter Nitaya is now head of the community. She produced her father’s guestbook, which I had signed at the time, and which is full of the signatures of musicians, academics, television producers, writers, and dealers in musical instruments. Prominent is the signature of former prime minister Chuan Leekpai, who had made his own way to Ban Lao and to Jarin’s workshop. Jarin had drawn a frame in biro around the entry.

A traditional Thai musical ensemble will often use a khlui flute, made from a species of bamboo known as mai mak. Because of the quality and reputation of the khlui made at Ban Lao, the flutes find a ready market. Most of them are delivered to Duriyaban, a music store on Tanao Road, on the other side of the river. The bamboo comes from Taipikul Putthabat, a village in the province of Saraburi, about a hundred kilometres northeast of Bangkok. This is limestone country, and the villagers cut the bamboo from the mountain behind Wat Phra Phutthabat, the stands growing on the mountain ledges providing exceptionally strong wood. First it is cut to length then left to dry in the sun, where it takes from fifteen to twenty days for the wood to dry completely, the villagers turning the bamboo over continuously to ensure consistent drying, the colour turning from green to a light yellow. The dried wood is cut according to the tone required, a short one producing a high tone and a long one a low tone. The surface is polished using ground brick wrapped in coconut husk, and holes drilled based on precise dimensions and spacing according to a formula passed down through the generations. Bees’ wax is poured into the flute and a heated rod inserted to melt the wax, leaving a smooth coating on the uneven inner surface and ensuring a consistency of sound. The more elaborate flutes are covered in rich markings made by dribbling liquid lead, which is heated in a charcoal-fired kiln. Ban Lao makes flutes from other materials too, and foreign buyers often order to specification. Nitaya showed me some ebony instruments tipped with ivory. Others are made from hardwoods brought out of the northern forests, and from ceramics. The most popular ones now, however, are made from pvc, and retail for about 50 baht. These sell in the mass market, being especially popular in schools. Ban Lao occupies two parallel alleys, and only about half a dozen families are making the flutes now. I couldn’t resist buying a bamboo flute, along with a pvc model as a comparison, but as my musicals skills do not extend beyond switching on a radio, they live upon my bookcase as souvenirs.

World History

World History

![Stalingrad: The Most Vicious Battle of the War [History of the Second World War 38]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432581864_1425486471_part-38.jpeg)