These were buoyant times for people in tune with the times—the young, the devil-may-care, factory workers with money in their pockets, many different types. But nearly all of them were city people. However, the tensions and hostilities of the 1920s exaggerated an older rift in American society—the conflict between urban and rural ways of life. To many among the scattered millions who tilled the soil and among the millions who lived in towns and small cities, the new city-oriented culture seemed sinful, overly materialistic, and unhealthy. To them change was something to be resented and resisted.

Yet there was no denying its fascination. Made even more aware of the appeal of the city by radio and the automobile, farmers and townspeople coveted the comfort and excitement of city life at the same time that they condemned its vices. Rural society proclaimed the superiority of its ways at least in part to protect itself from temptation. Change, omnipresent in the postwar world, must be resisted even at the cost of individualism and freedom.

One expression of this resistance was a resurgence of religious fundamentalism. Although it was especially prevalent among Baptists and Methodists, fundamentalism was primarily an attitude of mind, profoundly conservative, rather than a religious idea. Fundamentalists rejected the theory of evolution as well as advanced hypotheses on the origins of the universe.

What made crusaders of the fundamentalists was their resentment of modern urban culture. The teaching of evolution must be prohibited, they insisted. Throughout the 1920s they campaigned vigorously for laws banning discussion of Darwin’s theory in textbooks and classrooms. By 1929 five southern states had passed laws prohibiting the teaching of evolution in the public schools.

Their greatest asset in this crusade was William Jennings Bryan. After leaving Wilson’s Cabinet in 1915 he devoted much time to religious and moral issues, but without applying himself conscientiously to the study of these difficult questions. He went about the country charging that “they”—meaning the mass of educated Americans—had “taken the Lord away from the schools.” He denounced the use of public money to undermine Christian principles, and he offered $100 to anyone who would admit to being descended from an ape. His immense popularity in rural areas assured him a wide audience, and no one came forward to take his money.

The fundamentalists won a minor victory in 1925, when Tennessee passed a law forbidding instructors in the state’s schools and colleges to teach “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible.” The bill passed both houses by big majorities; few legislators wished to expose themselves to charges that they did not believe the Bible. Governor Austin Peay, a liberal-minded man, feared to veto the bill lest he jeopardize other measures he was backing. “Probably the law will never be applied,” he predicted when he signed it. Even Bryan, who used his influence to obtain passage of the measure, urged— unsuccessfully—that it include no penalties.

On learning of the passage of this act, the American Civil Liberties Union announced that it would finance a test case challenging its constitutionality if a Tennessee teacher would deliberately violate the statute. Urged on by friends, John T. Scopes, a young biology teacher in Dayton, reluctantly agreed to do so. He was arrested. A battery of nationally known lawyers came forward to defend him, and the state obtained the services of Bryan himself. The Scopes trial, also known as the “Monkey Trial,” became an overnight sensation.

Clarence Darrow, chief counsel for the defendant, stated the issue clearly. “Scopes isn’t on trial,” he said, “civilization is on trial. No man’s belief will be safe if they win.” The comic aspects of the trial obscured this issue. Big-city reporters like H. L. Mencken of the Baltimore Evening Sun flocked to Dayton to make sport of the fundamentalists. Scopes’s conviction was a foregone conclusion; after the jury rendered its verdict, the judge fined him $100.

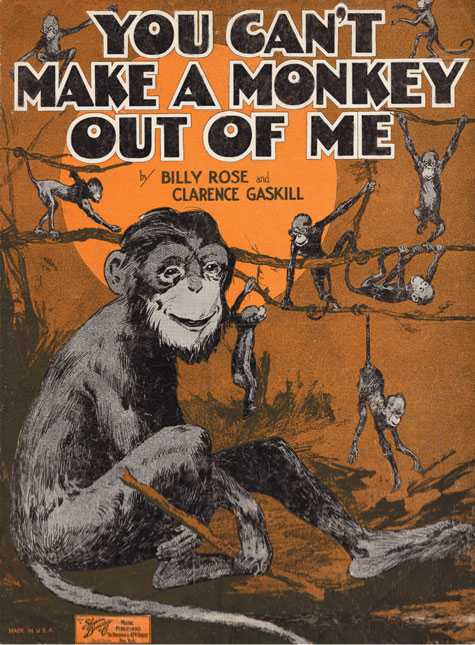

The Scopes trial was a media sensation; it even gave rise to popular songs, such as this one by Billy Rose.

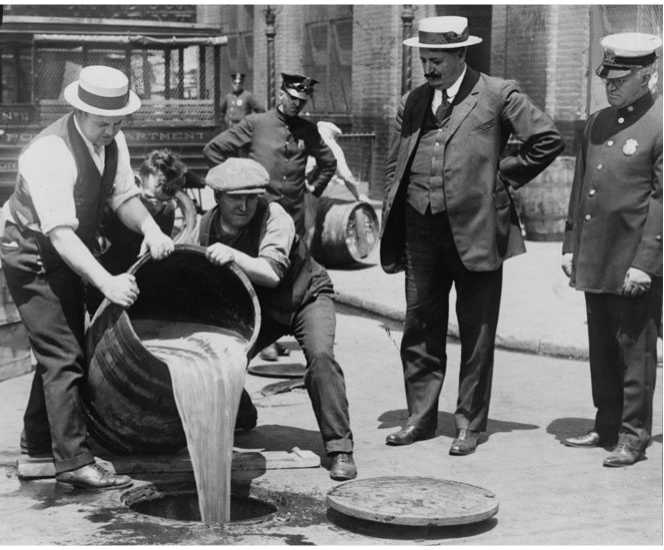

Federal agents pour liquor into a sewer during Prohibition.

Nevertheless, the trial exposed the danger of the fundamentalist position. The high point came when Bryan agreed to testify as an expert witness on the Bible. In a sweltering courtroom, both men in shirtsleeves, the lanky, rough-hewn Darrow cross-examined the aging champion of fundamentalism, exposing his childlike faith and his disdain for the science of the day. Bryan admitted to believing that Eve had been created from Adam’s rib and that a whale had swallowed Jonah. “I believe in a God that can make a whale and can make a man and make both do what He pleases,” he explained.

The Monkey Trial ended badly for nearly everyone concerned.

Scopes moved away from Dayton; the judge, John Raulston, was defeated when he sought reelection; Bryan died in his sleep a few days after the trial. But fundamentalism continued to flourish, not only in the nation’s backwaters but also in many cities, brought there by rural people in search of work. In retrospect, even the heroes of the Scopes trial—science and freedom of thought—seem somewhat less stainless than they did to liberals at the time. The account of evolution in the textbook used by Scopes was hopelessly deficient and laced with bigotry, yet it was advanced as unassailable fact. In a section on the “Races of Man,” for example, it described Caucasians as “the highest type of all. . . represented by the civilized white inhabitants of Europe and America.”

World History

World History